Workroom does good design. Every photobook I’ve come across that was designed by them feels right. Kim Yunho’s The Tedious Landscape is from Workroom’s Lájka Series. In Korean, the name reads phonetically as “Lah Ee Ca Series”; Leica Series. I’m not sure how or why it has re-transliterated to “Lajka.” Odd.

Moving on.

The Tedious Landscape II is, as might be obvious, the second in a series of projects. In The Tedious Landscape, Kim explored the outskirts. What does the country look like outside of the major cities?

The photographs in this book are of pageants, which often have the underlying goal of celebrating and promoting local specialty products. As most of these products are natural products or produce, these pageants tend to be put on in more rural regions or smaller towns or villages. As Kim Kyewon notes in the essay that closes the book, “Major cities do not have particular specialty products, and if they did, they would not need to promote them in such a way.” The Tedious Landscape II, then, extends Kim’s exploration of the periphery.

Another astute observation in Kim Kyewon’s essay is that though these photographs are of beauty pageants (whether the contestants are female, male, old or young), there are no beauties in the photographs. The scenes are photographed from a distance. In each, there is the whole stage filled with the full complement of contestants as well as other participants in the pageants–judges, audience members, photographers and assorted hangers-on. There is little action; the contestants in most of the photographs seem to be simply standing there, waiting.

In an earlier post, I spoke about the challenge of writing about work that I can’t fully understand as an outsider. There will always be aspects that are not apparent to me. An essay like Kim Kyewon’s can be invaluable in coming to a more complete understanding of a photographer’s intentions. I note this because I am going to steal (but attribute) an idea from Kim’s essay that is important to the work but that I would not have come up with myself.

The goal of these pageants is to promote the local specialty good. The contestants become double symbols not only as the most beautiful but also as a stand in for the local product. The pageant winners from one region are indistinguishable from the pageant winner from the next region. “The form in which they serve as symbols is repeated nationwide and results in a tedious [landscape].” (Kim uses the word “destiny” here, but as he earlier invoked the idea of topography, I think “landscape” is more appropriate.)

While in total the photographs may describe a tedious landscape, the individual images are rich with cultural detail, daily life and comedy. One of my favorite images is 395-800: 16 women stand on a rain slicked stage, one of them is speaking at the microphone, the others are standing in near identical poses and watching with a smile. The audience is hidden by their scrum of umbrellas. In another image, #355-601, 10 bodybuilders stand around on stage while a photographer and video crew record the winner being awarded his trophy. The non-winners stand around more or less awkwardly; the scene has ended but they’ve not been released from it yet. The audience here is only an ajashi with a camera and a handful of children fascinated by the spectacle before them. In #534-801 the audience is again huddled in the rain, this time wearing ponchos. On stage, six older women stand before drums as part of a traditional performance; a photographer crouches stage right. The front of the stage is draped with a mural of a field of flowers; at the image’s horizon line we are suddenly onto the stage. The top of the frame is kaleidoscopic tumble of lights, trusses and risers.

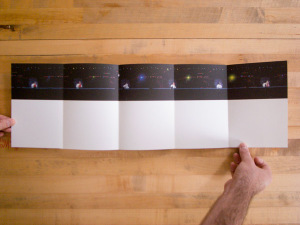

The book itself is roughly octavo sized, perfect bound with plain board covers glued front, rear and on the spine, and with a 3/4 height dust jacket with a panoramic image that wraps the book (technically this might be a belly band, but it feels more like a short dust jacket). The pages are heavyweight, nearly cardstock, which combined with the perfect binding allows them to lay flat but puts stress on the binding. The layouts are a mix of paired images across from one another and double truck spreads. Both layouts push the images right to the top where they bleed off of the page. Kyewon Kim’s essay comes after the plates and is on a different lighter paper stock. It is in both Korean and English. After the essay comes a list of plates and the artist’s C.V..

This is a tightly designed book of well considered and well made photographs. The clear and concise essay that gives context and added meaning to the photographs is a welcome bonus.

The Tedious Landscape II

Kim Yunho

Published by workroom press

Edited and Designed by workroom

Essay by Kim Kyewon

Translation by Kim Jeimin

First published 1 August 2008

Printed in Korea