One year ago I was writing about Ryu Eunkyu’s cheonghkadong, Village of the Sacred Cranes. Today, coincidentally, Ryu’s Memory of 100 years – Chuncheon Branch of Seoul Jail has come up in the queue.

Memory of 100 years is a slim paperback volume with a grainy black and white photograph of a nearly featureless expanse of a brick exterior wall wrapping around its cover. The title in white text is set against the photograph’s black sky. (My photographer’s mind notes the heavy handed red filter.) A black bar juts across the bottom of the front cover with the title repeated in Chinese and English; a small thumbnail size photograph of a guard tower is set in this black bar as well.

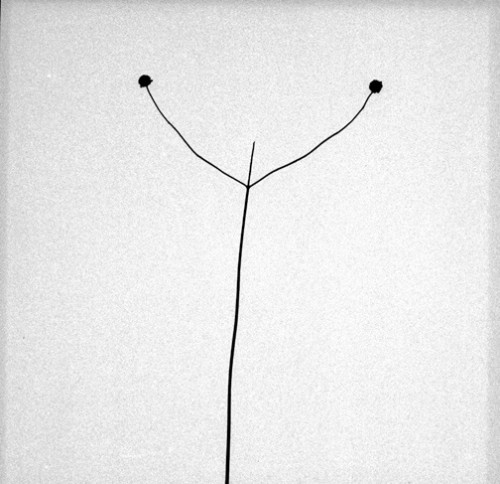

Like those in Village of the Sacred Cranes, the photographs in Memory of 100 years are shot in a gritty, black and white, small format documentary mode–though they take this aesthetic significantly further. The deep black skies, gritty texture and high contrast belie a highly subjective description of the former prison. This aesthetic choice both accentuates the textures of the subject while also romanticizing it. This romanticizing strikes me as counter productive; it creates a veil.

Ruin porn is all the rage lately, though Christopher Woodward might argue that ruin porn has been the rage for centuries. Decrepit, decommissioned prisons rank right up at the top of the contemporary ruin porn hierarchy. Functioning prisons generally hold less interest for photographers–though we’ll come back to Pete Brook’s Prison Photography anon. This is because photography of ruins is not (generally) about the subject. Instead, ruin porn is all about fetishizing the decay of structures and the ravages of time.

(A good counter-examples is Will Steacy’s Down These Mean Streets. While Steacy’s process has its weaknesses, his photographs of inner city decline are about the larger social issues of which the decay is simply a symptom. They aren’t fetish; they are protest.)

Memory of 100 years is ruin porn with a thin veneer of poetic historical gravitas plastered on top. It could be that understanding the essays (in Korean only) or captions (in Korean only) might push the ruin porn of the photographs into documentary, but I doubt it. The photographs are too loose–like snapshots from an hour long tour through an interesting historical building. Few of the photographs feel considered, only a handful suggest the passage of 100 years or tease out the trace of human experience left in that time. Mostly we see surfaces–worn and wearied surfaces to be sure, but still little more than light on surface.

Four photographs suggest alternative narratives that might have been made: 1. A tight view of the weathered door set into a narrow structure. To either side of the structure we see the prison walls beyond and a small square of sky above them. A single thin shaft of light cuts across the featureless facade of this structure from top left to bottom right. It leads the eye from the light square of sky down to shadow–it is like some kind of unmarked, perpetual sun dial. 2. Hand painted lettering in graceful brushstrokes is above a row of barred windows and below an upward thrusting roof line. The framing is off kilter. A large chunk of the concrete wall has fallen away and taken a chunk of lettering with it. 3. A slab of plaster or stone with handwritten text is nailed to a wall with rough square nails. Poetry? Exhortation? Psalms? Schedule? 4. A calendar from 1982 and two mimeographed pages are pasted to a wall. A grid of shadow, cast by a barred window, falls across them.

In these photographs time passes and artifacts, touched by the hands of men, remain. In these photographs are singular stories by which we can understand the greater history of this place. This shaft of light has been traveling across this surface for a century. Someone pasted up this calendar in order to track the passing days. It is this kind of attention to time and artifact that could have told a more nuanced story of the Chuncheon Branch of Seoul Jail beyond peeling paint, flaking concrete and weathered wood.

Illustrating one of the book’s two essays are half a dozen archival photographs of the prison in operation taken between 1909 and 1981. They put me in mind of Christian Patterson’s Redheaded Peckerwood with its deft weaving of artifacts, places and narratives in both historical time and present time; this is what Memory of 100 years might have aspired to.

Taking this thought further, I wonder what others might have made of this place and how others might have told this story. What artifacts might Bohnchang Koo have found and what might he have made of them? What unsettling details might Alyse Emdur have found? What spirits or ghosts might Kirk Gittings have teased from the architecture?

And, what does the present penal system look like? Pete Brooks’s Prison Photography doesn’t worry about the ruin of abandoned prisons; rather, it concerns itself with systemic personal ruin as part and parcel of the contemporary industrial prison complex. He gives voice to those buried away for years of their lives–or the entirety. This (unfair) comparison begs the questions: what documentary work could be done in the contemporary Korean prison system? Surely there are stories of passing time to be told in prisons at the height of operation, though there is likely less romance.

Ryu Eunkyu is a fine photographer. cheonghakdong, Village of the Sacred Cranes shows his ability to distill lived history in a place into photographs and to tell peoples’ stories. In Memory of 100 years, Ryu has been seduced by light and by texture and he has lost the thread of the story. For those who enjoy rough photographs of rough surfaces Memory of 100 years may please. For those who en joy a well told visual narrative, skip this title for Village of the Sacred Cranes, which is both a beautifully told story and a beautifully crafted object.

Memory of 100 years – Chuncheon Branch of Seoul Jail

Ryu Eunkyu

Tohyan Publishing

2010