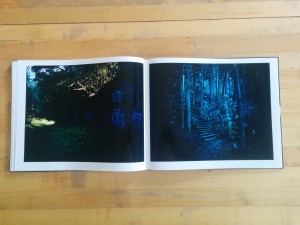

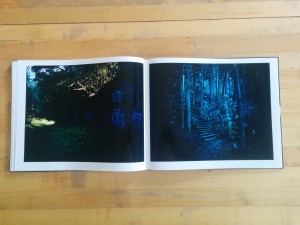

Photographing at night exposes the world in a new light. We are able to see things in ways that we cannot during daylight hours. Taewon Jang has gone out into the darkness to photograph stalled construction projects, remnants of abandoned factories and the nocturnal glow of functioning industrial sites so that we can see them, literally, in a different light.

Photographing at night exposes the world in a new light. We are able to see things in ways that we cannot during daylight hours. Taewon Jang has gone out into the darkness to photograph stalled construction projects, remnants of abandoned factories and the nocturnal glow of functioning industrial sites so that we can see them, literally, in a different light.

The light of the night is the opposite of the light of day. Daylight is external and falls onto the world–and does so with relative equality. At night, light jets outward from the subjects and pools close to its source leaving the rest of the world dark. By photographing at night–and by making use of the long exposures required by his large format camera, Jang traces the power relations (literal and metaphorical) of contemporary society.

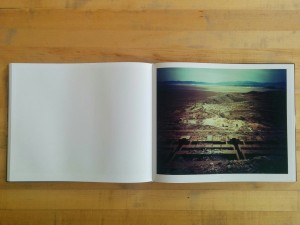

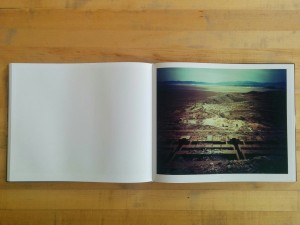

Jang began making photographs in Korea and Japan of stalled construction sites. Over the seven year period during which he photographed, he expanded his subject matter to include abandoned factories and functioning industrial sites as well as expanded his geographic area to include the United States. In total, he has photographed almost 400 different sites. Seventy-seven of these appear in Stained Ground.

Jang began making photographs in Korea and Japan of stalled construction sites. Over the seven year period during which he photographed, he expanded his subject matter to include abandoned factories and functioning industrial sites as well as expanded his geographic area to include the United States. In total, he has photographed almost 400 different sites. Seventy-seven of these appear in Stained Ground.

Distilling physical objects and their complex outer appearances into photographic form gave way to seeking evidence of the deep structures of our social contract. What is interesting is how the subjects suggest not only the social developments that begat them but also the continual development that will later consign them to obsolescence.

He describes the way his subjects evolved over the course of the seven year project in an interview with Suejin Shin included in the book: “In the beginning, I concentrated on the specific topography or the architecture, or perhaps a structure, or construction equipment, thinking that these elements could reveal the strange tension I felt at the site[s]… But then as I continued working on this project for a long time, I came to realize that what I saw was only a very small part of a larger picture… the places I photographed have changed beyond recognition or have even vanished from the map.”

He describes the way his subjects evolved over the course of the seven year project in an interview with Suejin Shin included in the book: “In the beginning, I concentrated on the specific topography or the architecture, or perhaps a structure, or construction equipment, thinking that these elements could reveal the strange tension I felt at the site[s]… But then as I continued working on this project for a long time, I came to realize that what I saw was only a very small part of a larger picture… the places I photographed have changed beyond recognition or have even vanished from the map.”

The light that illuminates these subjects and suffuses the photographs with an ethereal glow is itself a product of the development that these photographs trace. Likewise, Jang’s ability to photograph is a product of the development. Without the progress of the first and second industrial revolutions (and that continues in the third industrial–or technological, revolution of the present day) these photographs could not exist and their subjects would not exist. The advancements of each revolution bring about new technologies and new industries while leaving behind the old and setting the foundation for the next.

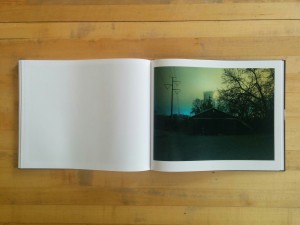

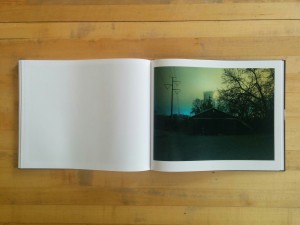

The last three photographs of Stained Ground can be read as a coda for understanding the book: In “SG U #415, 2013”, a vast windfarm spreads across the frame. Each windmill is marked off by the red glow of its warning light. The movement of some of the turbines’ blades over the course of the long exposure has blurred them into nothingness. In the background a miasma of green light sets off the dark and skewed horizon. Our own technology appears as “other.” The scene suggests both a technological miracle and an apocalypse brought about by the chain of changes these machines are intended, at least in part, to solve. The next photograph, “SG U #321, 2007,” is of a small, low industrial building. It’s garage door is dark but open–we can see the dim form of a white chair inside. To the right, the bare spindly branches of a tree loom over the building as if about to collapse onto it.  In the background the cooling towers of a power plant hover in a haze of brackish yellow clouds. Running from the foreground to the background in the left of the frame are high-tension power lines. They run straight back to a patch of blue cloud along the far horizon. The path to our current state has run along a line of iterative steps. Each successive revolution has brought the next. Photographically, the book ends with “SG K #420, 2007”. This photograph is one of only a handful that includes people and is the only photograph in which people are central. A group of 9 men (I assume they are men) are in a line in the center of the frame. They are dwarfed by the night around them. Five stand while four crouch or sit huddled on the ground. A line of hills run along the horizon and are dark against a multicolored sky. The ground on which the men are set is orange and indistinct. It is unclear if this is where perhaps some original industrial beginning occurred or where and how we’ll be left at some point in the future after our industry has run us to ground.

In the background the cooling towers of a power plant hover in a haze of brackish yellow clouds. Running from the foreground to the background in the left of the frame are high-tension power lines. They run straight back to a patch of blue cloud along the far horizon. The path to our current state has run along a line of iterative steps. Each successive revolution has brought the next. Photographically, the book ends with “SG K #420, 2007”. This photograph is one of only a handful that includes people and is the only photograph in which people are central. A group of 9 men (I assume they are men) are in a line in the center of the frame. They are dwarfed by the night around them. Five stand while four crouch or sit huddled on the ground. A line of hills run along the horizon and are dark against a multicolored sky. The ground on which the men are set is orange and indistinct. It is unclear if this is where perhaps some original industrial beginning occurred or where and how we’ll be left at some point in the future after our industry has run us to ground.

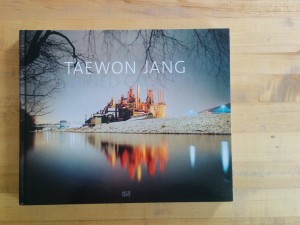

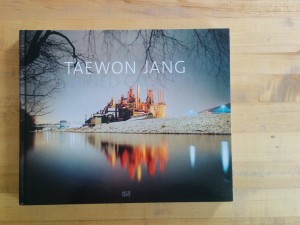

This is beautiful work and powerfully moving–in spite of the book’s humdrum design. As an object, Stained Ground is disappointing. As a point of comparison with another recent Hatje Cantz, Bae Bien-U’s Windscape‘s design pays attention to small details like the use of different papers for the text and plates and the use of a translucent matte dust-jacket that evokes the soft light of the photographs within. By comparison, Stained Ground lacks these small book maker’s touches. The cover is a good example of this: it is a garish glossy wrap with the title lost in the tones of the photograph over which it is set. Looking at Jang’s previous book, Black Midday, one sees a somewhat lower production value but a significantly greater attention to the design.

Stained Ground is a nice book to have on the shelf but not a necessary one. It doesn’t elicit delight. While it may seem odd to suggest that this should be the goal of a book whose subject matter is so somber, art books ought to be as much an object of delight as a carrier of content. One could imagine and certainly desire that design might have better served as mirror and amplifier to the content of Stained Ground. None of this is meant to discount the power of the photographs which are necessary and ought to be seen.

Stained Ground

Taewon Jang (site)

Edited by Suejin Shin and Markus Hartmann

Copyediting: Leina Gonzalez

Graphic Design and Typesetting: Andreas Platzgummer, Hatje Cantz

Production: Nadine Schmidt, Hatje Cantz

Typeface: Thesis, The Sans

Reproductions: Jan Scheffler, prints professional

Paper: Galaxi Keramik

Printing and Binding: DZA Druckerei zu Altenberg GmBH, Altenberg

2014

***

A brief post-script: A couple of American photographers making work contemporaneously with Jang are brought to mind by this book. Jang’s “SG U #405, 2013” recalls Mitch Epstein’s, American Power (as well as State of the Union, also published by Hatje Cantz). Epstein’s photographs examine the relationship of American society with industry, primarily in the form of energy production. Epstein places industry as ever present in the background of everyday life. Industry is there, but it remains, just barely, secondary to the human lives that it supports. Like Jang, his photographs are hesitant in passing judgement but present a troubling view. Less ambivalent is Will Steacy. Like Jang, Steacy spent long nights photographing America at night with a large format camera. In Down These Mean Streets, Steacy brought an agitprop sensibility to depicting the plight of the American City–in its archetypal and specific forms. The light in Jang’s photographs may hint at apocalypse and dystopia, but it has none of Steacy’s firebrand anger.

Photographing at night exposes the world in a new light. We are able to see things in ways that we cannot during daylight hours. Taewon Jang has gone out into the darkness to photograph stalled construction projects, remnants of abandoned factories and the nocturnal glow of functioning industrial sites so that we can see them, literally, in a different light.

Photographing at night exposes the world in a new light. We are able to see things in ways that we cannot during daylight hours. Taewon Jang has gone out into the darkness to photograph stalled construction projects, remnants of abandoned factories and the nocturnal glow of functioning industrial sites so that we can see them, literally, in a different light.  Jang began making photographs in Korea and Japan of stalled construction sites. Over the seven year period during which he photographed, he expanded his subject matter to include abandoned factories and functioning industrial sites as well as expanded his geographic area to include the United States. In total, he has photographed almost 400 different sites. Seventy-seven of these appear in Stained Ground.

Jang began making photographs in Korea and Japan of stalled construction sites. Over the seven year period during which he photographed, he expanded his subject matter to include abandoned factories and functioning industrial sites as well as expanded his geographic area to include the United States. In total, he has photographed almost 400 different sites. Seventy-seven of these appear in Stained Ground. He describes the way his subjects evolved over the course of the seven year project in an interview with Suejin Shin included in the book: “In the beginning, I concentrated on the specific topography or the architecture, or perhaps a structure, or construction equipment, thinking that these elements could reveal the strange tension I felt at the site[s]… But then as I continued working on this project for a long time, I came to realize that what I saw was only a very small part of a larger picture… the places I photographed have changed beyond recognition or have even vanished from the map.”

He describes the way his subjects evolved over the course of the seven year project in an interview with Suejin Shin included in the book: “In the beginning, I concentrated on the specific topography or the architecture, or perhaps a structure, or construction equipment, thinking that these elements could reveal the strange tension I felt at the site[s]… But then as I continued working on this project for a long time, I came to realize that what I saw was only a very small part of a larger picture… the places I photographed have changed beyond recognition or have even vanished from the map.”  In the background the cooling towers of a power plant hover in a haze of brackish yellow clouds. Running from the foreground to the background in the left of the frame are high-tension power lines. They run straight back to a patch of blue cloud along the far horizon. The path to our current state has run along a line of iterative steps. Each successive revolution has brought the next. Photographically, the book ends with “SG K #420, 2007”. This photograph is one of only a handful that includes people and is the only photograph in which people are central. A group of 9 men (I assume they are men) are in a line in the center of the frame. They are dwarfed by the night around them. Five stand while four crouch or sit huddled on the ground. A line of hills run along the horizon and are dark against a multicolored sky. The ground on which the men are set is orange and indistinct. It is unclear if this is where perhaps some original industrial beginning occurred or where and how we’ll be left at some point in the future after our industry has run us to ground.

In the background the cooling towers of a power plant hover in a haze of brackish yellow clouds. Running from the foreground to the background in the left of the frame are high-tension power lines. They run straight back to a patch of blue cloud along the far horizon. The path to our current state has run along a line of iterative steps. Each successive revolution has brought the next. Photographically, the book ends with “SG K #420, 2007”. This photograph is one of only a handful that includes people and is the only photograph in which people are central. A group of 9 men (I assume they are men) are in a line in the center of the frame. They are dwarfed by the night around them. Five stand while four crouch or sit huddled on the ground. A line of hills run along the horizon and are dark against a multicolored sky. The ground on which the men are set is orange and indistinct. It is unclear if this is where perhaps some original industrial beginning occurred or where and how we’ll be left at some point in the future after our industry has run us to ground.  Despite the grand subject and lofty conceptual framework, Kyoungtae Kim’s Cathedral de Lausanne 1505–2022 is a rather modest affair in both its design and material construction. The brief text by Kyungyong Lim on the rear cover is short, to the point and written in language that a layperson can understand. The sum of these choices is an approachable and engaging book that encourages the reader to reconsider his or her reading of iconic landmark buildings.

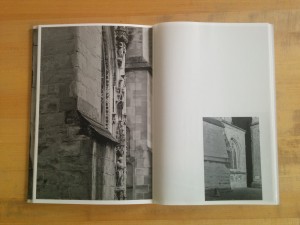

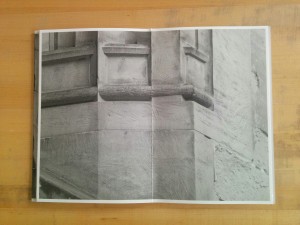

Despite the grand subject and lofty conceptual framework, Kyoungtae Kim’s Cathedral de Lausanne 1505–2022 is a rather modest affair in both its design and material construction. The brief text by Kyungyong Lim on the rear cover is short, to the point and written in language that a layperson can understand. The sum of these choices is an approachable and engaging book that encourages the reader to reconsider his or her reading of iconic landmark buildings.  The interior pages are an alternating mix of uncoated heavyweight stock and lightweight coated stock. The heavyweight pages generally contain sections of wall where either a stone is marked with the date of its replacement or sections of stone where repair work is being done. These photographs are all relatively tight close ups and printed full page. The lightweight coated pages contain longer views of either work sites or larger sections where renovations have been completed and are printed roughly quarter page. The book closes with two scenic shots of the cathedral from either end–these are printed back to back on the lightweight stock and the images ghost into one another through the paper.

The interior pages are an alternating mix of uncoated heavyweight stock and lightweight coated stock. The heavyweight pages generally contain sections of wall where either a stone is marked with the date of its replacement or sections of stone where repair work is being done. These photographs are all relatively tight close ups and printed full page. The lightweight coated pages contain longer views of either work sites or larger sections where renovations have been completed and are printed roughly quarter page. The book closes with two scenic shots of the cathedral from either end–these are printed back to back on the lightweight stock and the images ghost into one another through the paper.  As I wrote about Kim’s

As I wrote about Kim’s