Interpreters begins with divergence. A Western reader, out of habit, opens the book left to right. The title page and table of content page force this reader to turn the book so the pages open upwards. Flipping to page five, which contains the first plate in the book, the reader is forced again to turn the book so that he is reading right to left. A Korean reader would likely note the orientation of the Hangul on the cover and open the book as intended–though the orientation of the English characters on the cover, title page and table of contents might cause some doubt. Perhaps an insider is not an insider is not an insider.

Interpreters begins with divergence. A Western reader, out of habit, opens the book left to right. The title page and table of content page force this reader to turn the book so the pages open upwards. Flipping to page five, which contains the first plate in the book, the reader is forced again to turn the book so that he is reading right to left. A Korean reader would likely note the orientation of the Hangul on the cover and open the book as intended–though the orientation of the English characters on the cover, title page and table of contents might cause some doubt. Perhaps an insider is not an insider is not an insider.

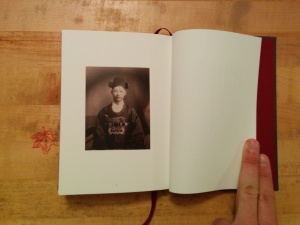

The first set of plates are five photographic portraits from the early twentieth century made of Koreans by visitors to Korea–likely European or Japanese. Given their stylistic differences, these photographs were almost certainly made by different photographers. In all five images the subjects gaze directly into the camera’s lens. Their expressions are taut and hard to read, though it is impossible to know if this is out of reticence, hostility or simply the discomfort of holding still for a long exposure.

The first set of plates are five photographic portraits from the early twentieth century made of Koreans by visitors to Korea–likely European or Japanese. Given their stylistic differences, these photographs were almost certainly made by different photographers. In all five images the subjects gaze directly into the camera’s lens. Their expressions are taut and hard to read, though it is impossible to know if this is out of reticence, hostility or simply the discomfort of holding still for a long exposure.

These subjects are foreign to the photographs’ intended audience. The photographs were meant to communicate and accentuate the subjects’ Otherness. For a contemporary Western viewer these subjects are doubly foreign: they are seen through both a cultural and temporal divide. Even a contemporary Korean viewer of these photographs sees them through the distance of nearly a century.

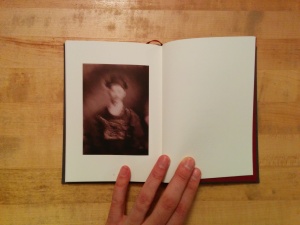

Chun took this foreignness, this Otherness, and created a lens from it. He showed these photographs to ten painters living in Bremen, Germany and asked each to select one photograph to make a realistic painting from. Chun then used the very long exposures he is known for to photograph these painters confronting their paintings face to face. Chun’s photographs are layers of cultural encounter.

Park Pyung Jong makes much of this layering of encounters in his essay included in Interpreters, “The Encounter With the Encounter.” The essay is helpful in understanding what we are encountering in Chun’s photographs. It is the only explanation of the photographer’s process and conceptual framework; neither are self evident from even a close reading of the conceptual photographs alone. Park contends that the process of perception through which Otherness is broken down and internalized enables the growth of the Self and that the encounter with the Other “heralds the beginning of the [sic] meaning.”

Park Pyung Jong makes much of this layering of encounters in his essay included in Interpreters, “The Encounter With the Encounter.” The essay is helpful in understanding what we are encountering in Chun’s photographs. It is the only explanation of the photographer’s process and conceptual framework; neither are self evident from even a close reading of the conceptual photographs alone. Park contends that the process of perception through which Otherness is broken down and internalized enables the growth of the Self and that the encounter with the Other “heralds the beginning of the [sic] meaning.”

Interpreters is not so much layers of encounters as layers of interpretation. The original photographers interpreted the subjects who sat before their cameras. The painters interpreted these photographs. Chun interpreted these encounters. Park interpreted Chun’s process and intent. Without the understanding gained from Park’s essay, how is a reader to interpret the blur and distortion that Chun’s process adds to the original portraits? These layers upon layers of interpretation do more to obfuscate through the addition of information than they do to pare away to a core truth. Without Park’s explanation, a reader might reasonably conclude that an encounter with the Other only makes the Other more foreign and less knowable.

Opening the book for the first time, one is struck by the force of the five original portraits. The directness of the subjects’ stares across nearly a century is disorienting. That direct encounter presents questions that one can find at least partial answers to in the photographs themselves and in how the subjects were represented. In contrast, encountering the same photographs through the mediation of Chun’s process is confusing. Why are the portraits suddenly distorted? Why are they hidden behind a veil of blur? Even the long exposure of Chun’s portrait process would not create blur from a static object. In what way is this an interpretation? A close reading is not enough to find answers directly from the photographs. Without reading Park’s explanation of the photographs and the process of their creation, a reader would be hard pressed to find significant insight or meaning.

While the amplified layer of time in Chun’s previous portraits poses interesting questions regarding the photographic portrait, Interpreters hides such questions under too many obfuscating layers of process and concept.

Interpreters

Kyungwoo Chun

Essay: Park Pyung Jong

Design: Space shinjeung

Published by Youngsook Song, Ga-Hyeon Foundation of Culture; The Museum of Photography, Seoul

Supported by Gaain Gallery, Seoul