National Song Contest is like a self-similar view of Korea. One can extrapolate out from these photographs and examine nearly any facet of Korean culture. This is hyperbole, but this series of photographs from Byun Soon Choel has a definite fractal-like quality to it. And, perhaps most importantly, it is chock full of zany fun.

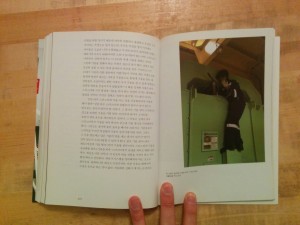

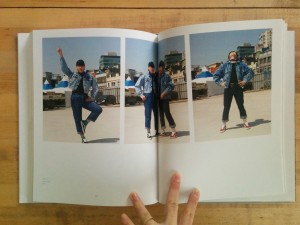

The nominal subject of National Song Contest is contestants of the television show of the same name. Running for over thirty years, the show’s premise is much like “America’s Got Talent,” if that show were combined with a comedic circus act. Choel’s subjects are full of ardor; each is a uniquely live wire. Choel does not hold them back. He seems rather to push them into hamming it up for the camera–pushing them in such a way that their acts become archetypes.

The nominal subject of National Song Contest is contestants of the television show of the same name. Running for over thirty years, the show’s premise is much like “America’s Got Talent,” if that show were combined with a comedic circus act. Choel’s subjects are full of ardor; each is a uniquely live wire. Choel does not hold them back. He seems rather to push them into hamming it up for the camera–pushing them in such a way that their acts become archetypes.

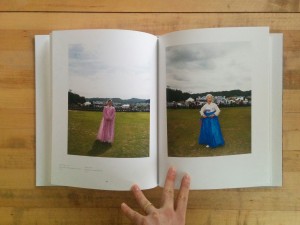

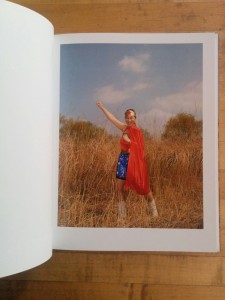

Midday sun boosted by a pop of strobe bathes the contestants in bright, intense color and freezes their antics as they sing, dance and pose for Choel’s camera. Individual contestants and a handful of groups pose either before or after their star turn. They stand in fields, parks, parking lots, sidewalk niches, press stages and the occasional hotel hallway. These landscapes mirror and reinforce the numerous facets of Korean-ness that are suggested in the personas that the subjects project and the costumes that they wear.

These costumes range from classic to questionable with stops in eclectic bohemia, historical reminiscence, and K-Pop striving. There are hanbok and white tuxedo jackets; pink pants and floral prints; suspenders and athletic wear; sequins and plaids. There are fedoras and berets; rubber sandals and rubber boots; bonnets and afro wigs; sneakers and stilettos. There is even a muscle padded superman. These are combined in hilarious and unexpected ways.

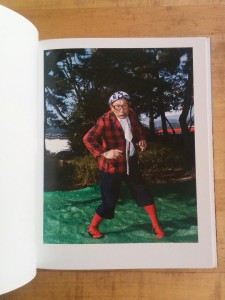

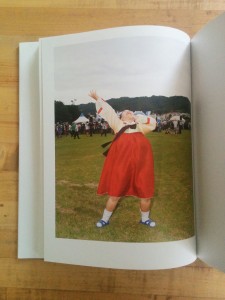

It is hard to reduce the project to a representative sample, so I’ll simply note one image that makes me smile. A haraboji stands on a foreground of astroturf with a screen of pine trees behind him that partially obscure a palace wall to the left and a row of low mountains receding into the blue distance to the right. His outfit is a chaotic confabulation of color, pattern and style. From the ground up we see: On his feet he wears bright red athletic cleats and red knee high socks. We can see that they are knee high socks because his loose-cut blue dress slacks are short, ending just below his knee. His pin-striped blue dress shirt has decorative stitching on the collar. Covering this shirt is a red lumberjack plaid sports coat; a mis-tied pink and gold necktie juts out from the jacket (with its tail spilling out below). He wears oversized round glasses and a blue and white bubble (floral?) patterned beret (or is it a shower cap?). His body is twisted in mid-gesture, and his face is screwed into the lead-in of another gesture. His hands are held gracefully, as though taken from a tai-chi pose or lifted from a Renaissance painting of saints.

It is hard to reduce the project to a representative sample, so I’ll simply note one image that makes me smile. A haraboji stands on a foreground of astroturf with a screen of pine trees behind him that partially obscure a palace wall to the left and a row of low mountains receding into the blue distance to the right. His outfit is a chaotic confabulation of color, pattern and style. From the ground up we see: On his feet he wears bright red athletic cleats and red knee high socks. We can see that they are knee high socks because his loose-cut blue dress slacks are short, ending just below his knee. His pin-striped blue dress shirt has decorative stitching on the collar. Covering this shirt is a red lumberjack plaid sports coat; a mis-tied pink and gold necktie juts out from the jacket (with its tail spilling out below). He wears oversized round glasses and a blue and white bubble (floral?) patterned beret (or is it a shower cap?). His body is twisted in mid-gesture, and his face is screwed into the lead-in of another gesture. His hands are held gracefully, as though taken from a tai-chi pose or lifted from a Renaissance painting of saints.

This image, as well as any other from the project, brings to bear the full emphasis of joyful visual expression that the contestants parade before the camera. These folks are having a good time and they want you to see it.

It would be naive to imagine that not one of these contestants harbors hope of fame or fortune through the contest, but it is entirely the joy of the performance that drives the photographs. If one were to shoot a similar project here in America, it would likely by tinged by an ironic sadness of the desperation for fame or the mocking overtones of the ‘loser edit.’ In contrast, Cheol’s lens affectionately finds antic joy.

It would be naive to imagine that not one of these contestants harbors hope of fame or fortune through the contest, but it is entirely the joy of the performance that drives the photographs. If one were to shoot a similar project here in America, it would likely by tinged by an ironic sadness of the desperation for fame or the mocking overtones of the ‘loser edit.’ In contrast, Cheol’s lens affectionately finds antic joy.

The portraits are generally full page, one to a spread and captioned on the opposing page with the location and year each was created. The oversized volume is nicely printed and well designed, though the materials are hardly sumptuous. One wishes that the visual antics of the portraits might have made their way into the design, at least a little–Martin Parr’s Life’s a Beach comes to mind as an example of a publication in which the physical design took its cues from the photographs.

One might be tempted to label and dismiss Choel’s National Song Contest as camp, but this would be a mistake. The loose typographical framework, reminiscent of August Sanders’ expansive People of the 20th Century, becomes a cipher through which Choel is able to decode the breadth of “Korean-ness”. It is not only the contestants and their personas that transmit this information, but also the details of landscape and location that are the backdrop of the portraits. Likewise, it would be a mistake to forget that the photographs are a cacophony of crazy performances being conducted in enthusiastic ernest for the camera. The photographs are, quite simply, a lot of fun.

One might be tempted to label and dismiss Choel’s National Song Contest as camp, but this would be a mistake. The loose typographical framework, reminiscent of August Sanders’ expansive People of the 20th Century, becomes a cipher through which Choel is able to decode the breadth of “Korean-ness”. It is not only the contestants and their personas that transmit this information, but also the details of landscape and location that are the backdrop of the portraits. Likewise, it would be a mistake to forget that the photographs are a cacophony of crazy performances being conducted in enthusiastic ernest for the camera. The photographs are, quite simply, a lot of fun.

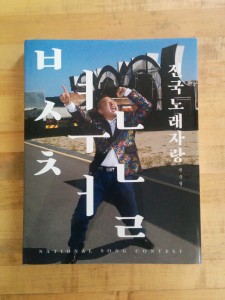

National Song Contest

Byun Soon Cheol

Published by G Colon

2014

Yoon Seungjun’s Automatic Description is a book of car photographs. These photographs are not your everyday glossy advertisement for this years latest iteration of automotive desire. There is no glitz, no sparkle, no sex appeal. These cars are dead.

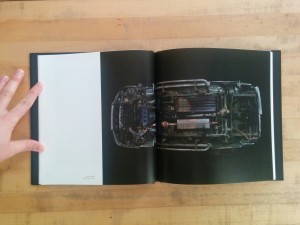

Yoon Seungjun’s Automatic Description is a book of car photographs. These photographs are not your everyday glossy advertisement for this years latest iteration of automotive desire. There is no glitz, no sparkle, no sex appeal. These cars are dead.  Automatic Description is broken into chapters that build one upon the other. The book begins with “Anatomical Chart – appropriation,” a typological series of images of individual car’s under carriages shot against a black ground. These photographs reduce the automobile to its basic structural form, minus wheels. We see the body frame with the suspension structures, transmission, driveshaft, and exhaust systems hanging from it. With their wheels removed and reoriented in space, these automobiles are no longer vehicles but rather abstract forms. Looking closely, one can find narratives in the abstraction: oil leaks, broken drive shafts, scrapes, rust and burn (?) marks. There are stories in these forms however banal they might be.

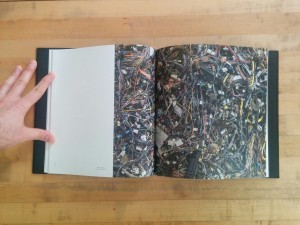

Automatic Description is broken into chapters that build one upon the other. The book begins with “Anatomical Chart – appropriation,” a typological series of images of individual car’s under carriages shot against a black ground. These photographs reduce the automobile to its basic structural form, minus wheels. We see the body frame with the suspension structures, transmission, driveshaft, and exhaust systems hanging from it. With their wheels removed and reoriented in space, these automobiles are no longer vehicles but rather abstract forms. Looking closely, one can find narratives in the abstraction: oil leaks, broken drive shafts, scrapes, rust and burn (?) marks. There are stories in these forms however banal they might be. Chapter two, “Anatomical Chart – combination,” moves from individual vehicles to the aggregation of them. Vehicles are no longer individual stories. Instead, they interlock in stacks and heaps. Crumpled cars are crumpled in a pile. Hundreds of gas tanks are mounded together. Wiring harnesses are enmeshed in a chaotic singular mess. Pipes of every description writhe together like so many snakes in a pit. The singular story has given way to a history of multitudes. Yoon brings his camera in close for these photographs. We see no ground; the subject fills the frame. We are again seeing this automotive wreckage as abstraction.

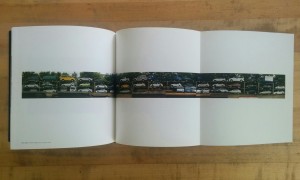

Chapter two, “Anatomical Chart – combination,” moves from individual vehicles to the aggregation of them. Vehicles are no longer individual stories. Instead, they interlock in stacks and heaps. Crumpled cars are crumpled in a pile. Hundreds of gas tanks are mounded together. Wiring harnesses are enmeshed in a chaotic singular mess. Pipes of every description writhe together like so many snakes in a pit. The singular story has given way to a history of multitudes. Yoon brings his camera in close for these photographs. We see no ground; the subject fills the frame. We are again seeing this automotive wreckage as abstraction.  “Scraped Car Chart – parade” is the third chapter and takes us off into the new territory of documentary context. Yoon has pulled back to show us the space in which these cars are resting. We see the rows of racks and risers on which the cars rest. Some of the vehicles are half dismantled; others seem as shiny as new. Sunlight glints off of chrome and polish, still. In the middle of the chapter a gatefold presents a long panoramic image of column after column of junked cars. There are obvious joints in the image; it is not a singular panorama. Yoon has constructed this image–no different than we have constructed this entire infrastructure of disposal (such as it is). Just as the infrastructure of roads, highways and city streets has been built to accommodate the relentless drive of automobile culture so has an infrastructure been built to support the end stage inherent in consumerism. When millions are buying cars, millions are inevitable discarding them as well.

“Scraped Car Chart – parade” is the third chapter and takes us off into the new territory of documentary context. Yoon has pulled back to show us the space in which these cars are resting. We see the rows of racks and risers on which the cars rest. Some of the vehicles are half dismantled; others seem as shiny as new. Sunlight glints off of chrome and polish, still. In the middle of the chapter a gatefold presents a long panoramic image of column after column of junked cars. There are obvious joints in the image; it is not a singular panorama. Yoon has constructed this image–no different than we have constructed this entire infrastructure of disposal (such as it is). Just as the infrastructure of roads, highways and city streets has been built to accommodate the relentless drive of automobile culture so has an infrastructure been built to support the end stage inherent in consumerism. When millions are buying cars, millions are inevitable discarding them as well.