Does Spring Come to Stolen Fields fairly brims with nuanced intent. It is a book with a mission.

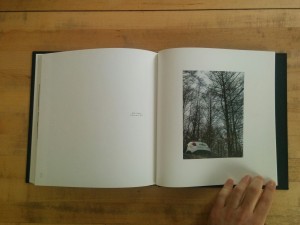

The photographs in Does Spring Come to Stolen Fields are, for the most part, lyrical pastoral scenes taken in Fukushima and its surrounds in the year after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. There is a quiet that descends over the mostly depopulated scenes. In much the same way that the poem from which this book takes its title is a poem of protest only in its opening and closing lines, it is only in the foreword and afterword that this book makes its clearest protests. The photographs may be at once beautiful and unsettling, but they are indirect. It is only through the thoughtful polemics by Han Hong-koo and Suh Kyung-sik that the full weight of their protestation becomes evident.

Two photographs in particular bring the book’s main theme into clear focus: In the first, a persimmon tree dominates the foreground with an orchard spreading out behind it. Dozens of ripe fruits hang heavy on the tree. In the background, dozens, perhaps hundreds, of equally ripe fruits await a harvest that will never come. The midday sun of everyday, any day, highlights the tree’s tangle of branches and the carpet of unmown grass below it. In the second, a ruffled beach recedes into the distance. Round stones and bits of small debris litter the sand. Two hardscrabble pine trees stand resolutely in the center of the frame. Waves roll in without end from the left. An empty, low and brown field extends from the trees right out to the background. In the far distance, straight out the shoreline, sit the boxy shapes familiar from newscasts of the Fukishima disaster.

What future do these lands have? Even as the disaster recedes into the past, its effects remain present. The news cameras may have moved on but despite significant clean up efforts the fallout of the disaster will not disappear any time soon.

In his afterword, Suh Kyung-sik recounts a young farmer stopping the group that he and the photographer were traveling with to berate them for coming to make their pictures but not doing anything to help the people who have been most directly affected. This highlights a central problem with a book like this: It’s impact will likely be limited. However good a photographer’s intentions, however strong the photographs, however horrific their subject it is difficult for photographs alone to move people to create change. Photographers have been showing us in detail the horror of war for a century and a half and yet we’re no closer to ending war.

Chung counters this problem in two ways. This book is not a one off exercise. It is part of the photographer’s ongoing interest in and concern with the peace movement’s opposition to the nuclear industry. Chung has previously published two books on the topic of nuclear power. His earlier publications were meant to show the insidious threat that we have become complacently inured to. Does Spring Come to Stolen Fields is a tragic extension of these earlier projects. More importantly, Chung partners with others working in the peace and non-proliferation movements. His photographs and books are meant to be bricks in a larger struggle.

And, struggle or protest is exactly what these photographs are. The book’s title is drawn from the poem Does Spring Come to Stolen Fields that was published in 1926 by Lee Sang-hwa. The poem led to the shuttering of the magazine Gaebyeok in which it was first published and in Lee’s arrest for anti-Japanese activities. The poem was an absolutely anti-colonial protest against the Japanese occupation.

At first glance, a Korean poem protesting the Japanese occupation of Korea a century earlier might seem an odd or even errant choice as a primary reference point for a book calling attention to the fallout from a present day natural disaster in Japan. Han and Suh both take pains to elucidate how the reference is both valid and useful. Suh in particular teases out interesting inferences from the comparison.

By TEPCO and the Japanese government’s estimates, it will take decades for the Fukushima Daiichi reactors to be fully shut down. Radiation will be a problem for decades longer, if not centuries. The fallout from this disaster will long reverberate–much as the fallout from the Japanese occupation of Korea has reverberated in national politics and personal histories for the last 100 years. In this mirroring of long-term fallout, Suh sees the seeds of dialogue towards the finding of common ground.

Lee’s poem was a protest against the occupation–in particular the theft of Korean lands in the name of increased productivity. The Fukushima disaster might not be a colonial occupation, but it presents a situation in which the national government in cahoots with powerful industrial lobbies has stolen peoples’ lands. There is right and there is wrong. When wrongs are perpetrated against the people, the powerful, whether working through the guise of a foreign or domestic government, must be held accountable to the people.

Accountability is a tricky endeavor, however. Chung, Han and Suh are all aligned against the nuclear industry and its supporters in government. The nuclear industry goes back to World War II. In this way the Japanese become the first victims of the nuclear industry–as well as the perpetrators of gross human rights violations throughout Asia. Han and Suh both point out that the deaths of hundreds of thousands in Nagasaki and Hiroshima do not excuse the country for its brutal actions that led to the deaths of millions throughout Asia. Conversely, the wrongs perpetrated against Korea during the occupation do not allow Koreans to wash their hands of what has happened at Fukushima and to ignore the present day victims of this present nuclear disaster. However fraught a relationship might be, a natural/nuclear disaster cannot in good conscience be read as retribution, though nor should it absolve a country of past wrongs or obviate the need for apology.

(As a side note: the intended audience for this book is primarily domestic, i.e. Korean. When I write that Koreans cannot wash their hands of what has happened at Fukushima, it would be equally fair to read that as “the international community cannot wash its hands of the disaster.” This is a disaster for all humanity. Likewise, the threat and opportunity of nuclear energy is a something that must be considered by all humanity.)

All of this cannot be communicated by the photographs alone. Chung’s photographs show the landscapes stolen by the disaster: fields that can no longer be tilled, orchards that cannot be harvested, homes that cannot be lived in, highways that cannot be followed and beaches that cannot be enjoyed. Nature herself continues on. Weeds poke through the pavement of a bridge. Birds wheel overhead. Flowers erupt from beneath frost. The ocean rolls and rolls and rolls onto the beach.

In one photograph of a nursing home interior, the high water line reaches nearly to the clock mounted high on the wall. The paint above the line is clean, except where water has splashed. Below, the wall is a fractal mess of dried mud, and the floor is coated in silt left by the receding water. Suh relates his experience of seeing this photograph for the first time and of Chung relating that the clock continued to run as if nothing had happened. This building can no longer accommodate human activity and yet time has gone on. The clock continues to run. Even once its battery gives out, time will still flow.

Spring will come to the fields in Chung’s photographs, but it will matter little to those from whom they’ve been stolen.

Does Spring Come to Stolen Fields

Chung Ju-ha

Essays: Han Hong-koo and Suh Suh Kyung-sik

Published by Noonbit Publishing Co.

2012

My last visit to Seoul came at an interesting time. My own country had just elected an orange-hued charlatan (but much loved by some, apparently) to its highest office, sparking immediate protests. Seoul was in the midst of weekly and growing protests each Saturday against an expanding presidential scandal. And multiple elections were approaching in Europe with right-wing parties gaining ground in polls. There are many people marching in the streets lately who want to see change. With all of this as a background, I came across Park Seung-hwa’s Protest published by Listen to the City in The Book Society’s stacks.

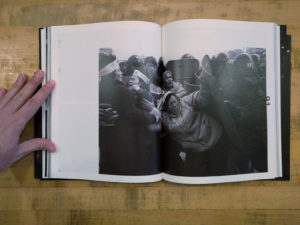

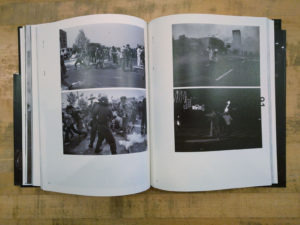

My last visit to Seoul came at an interesting time. My own country had just elected an orange-hued charlatan (but much loved by some, apparently) to its highest office, sparking immediate protests. Seoul was in the midst of weekly and growing protests each Saturday against an expanding presidential scandal. And multiple elections were approaching in Europe with right-wing parties gaining ground in polls. There are many people marching in the streets lately who want to see change. With all of this as a background, I came across Park Seung-hwa’s Protest published by Listen to the City in The Book Society’s stacks. The photographs run the gamut from dramatic confrontation to quiet determination. There are individuals acting alone and huge crowds of people acting in concert. We are shown moments of grace and moments of violence. On one page protesters look down from a rooftop at the police below. On the next page it is the police who are on the roofs looking down on the people below. The one constant is a sense of confrontation and anger, at turns explosive and subdued. The content of the photographs is mirrored by the divided compositions in contrasty and grainy yet richly rendered black and white.

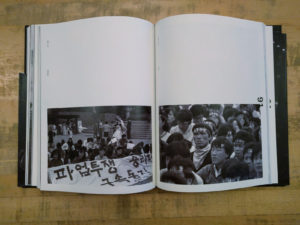

The photographs run the gamut from dramatic confrontation to quiet determination. There are individuals acting alone and huge crowds of people acting in concert. We are shown moments of grace and moments of violence. On one page protesters look down from a rooftop at the police below. On the next page it is the police who are on the roofs looking down on the people below. The one constant is a sense of confrontation and anger, at turns explosive and subdued. The content of the photographs is mirrored by the divided compositions in contrasty and grainy yet richly rendered black and white.  Park draws from his own work as well as the work of the four other photographers who formed the National Photography Research Society (민족사진연구회). These five photographers, Kwon San-Ki, Park Seung-hwa, Song Hyeok, Lee Sohye, Lim Seok Hyun, came together photographing the protests. They gathered around an older photographer, Park Yong-su. Their efforts, specifically as culminated in the publication ofProtest, are a kind of extension of Park Yong-su’s 1989 book The Road of the People (민중의 길), in which he documented the events between the 1985 sit-in demonstration at the American Cultural Center in Seoul and Chun Doo-hwan’s going to Baekdamsa in 1988. Despite this added context, a straight documentary reading remains problematic.

Park draws from his own work as well as the work of the four other photographers who formed the National Photography Research Society (민족사진연구회). These five photographers, Kwon San-Ki, Park Seung-hwa, Song Hyeok, Lee Sohye, Lim Seok Hyun, came together photographing the protests. They gathered around an older photographer, Park Yong-su. Their efforts, specifically as culminated in the publication ofProtest, are a kind of extension of Park Yong-su’s 1989 book The Road of the People (민중의 길), in which he documented the events between the 1985 sit-in demonstration at the American Cultural Center in Seoul and Chun Doo-hwan’s going to Baekdamsa in 1988. Despite this added context, a straight documentary reading remains problematic.  Park’s introduction to Protest is helpful in reframing these photographs. He reveals that the contemporary making of the book, was an effort to “uncover [his] faded passion and shell of belief” represented by photographs made over two decades earlier. These photographs are personal. They project “a kind of political intention” and come from a “‘biased’ point of view.” The photographs are at once “records, commemorations and, in a way, propaganda.”

Park’s introduction to Protest is helpful in reframing these photographs. He reveals that the contemporary making of the book, was an effort to “uncover [his] faded passion and shell of belief” represented by photographs made over two decades earlier. These photographs are personal. They project “a kind of political intention” and come from a “‘biased’ point of view.” The photographs are at once “records, commemorations and, in a way, propaganda.” Protest then is a lament or reckoning rather than a dry documentation. It is a sober reconsideration of that time and where the flow of time has ultimately led. Despite having “walked so far away from the days of the photos…the day [Park] has dreamed of during those old days has yet to come.” He asks that the there be no mention of a “legendary saga” when reading these photos and notes that “the past [is] often glorified under the astute compromise.” We all, in order to live our lives in some measure of comfort, make compromises in our beliefs and actions; Park subtly suggests that if we are honest with ourselves, perhaps our compromises are really betrayals of our convictions.

Protest then is a lament or reckoning rather than a dry documentation. It is a sober reconsideration of that time and where the flow of time has ultimately led. Despite having “walked so far away from the days of the photos…the day [Park] has dreamed of during those old days has yet to come.” He asks that the there be no mention of a “legendary saga” when reading these photos and notes that “the past [is] often glorified under the astute compromise.” We all, in order to live our lives in some measure of comfort, make compromises in our beliefs and actions; Park subtly suggests that if we are honest with ourselves, perhaps our compromises are really betrayals of our convictions.  In a similar vein, the book presents a kind of critique of photo-journalism and documentary photography. Park defines photographs as a “record of facts.” And yet he goes on to say that a myriad of photos can be created of a single scene. “These photos are all based on facts but far away from the truth.” Park does not claim to be publishing any kind of definitive view of these events. He goes so far as to call attention to the other photographers who were photographing these same events and whose photographs, if they could have been included in the book, would have made for “a finer and richer record.”

In a similar vein, the book presents a kind of critique of photo-journalism and documentary photography. Park defines photographs as a “record of facts.” And yet he goes on to say that a myriad of photos can be created of a single scene. “These photos are all based on facts but far away from the truth.” Park does not claim to be publishing any kind of definitive view of these events. He goes so far as to call attention to the other photographers who were photographing these same events and whose photographs, if they could have been included in the book, would have made for “a finer and richer record.”  These photographs and Park’s view of their creation and value are appropriate to consider here in America in light of the protests happening in the present day. As may be self evident but certainly worth reiterating: protest in and of itself won’t bring about change. Those bodies in the streets lifting their voices may create the changes they seek or may simply gratify their desire to speak their piece. In order to effect change there must be concrete political action being taken before and after the marches, protests and demonstrations. Desiring change does not necessarily create change. It requires long years of hard work. It is equally likely that in thirty years we will look back and wonder where it all got them. Compromises for our own comfort will leave us “wandering around, or rather drifting away.”

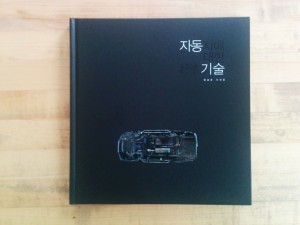

These photographs and Park’s view of their creation and value are appropriate to consider here in America in light of the protests happening in the present day. As may be self evident but certainly worth reiterating: protest in and of itself won’t bring about change. Those bodies in the streets lifting their voices may create the changes they seek or may simply gratify their desire to speak their piece. In order to effect change there must be concrete political action being taken before and after the marches, protests and demonstrations. Desiring change does not necessarily create change. It requires long years of hard work. It is equally likely that in thirty years we will look back and wonder where it all got them. Compromises for our own comfort will leave us “wandering around, or rather drifting away.”  Yoon Seungjun’s Automatic Description is a book of car photographs. These photographs are not your everyday glossy advertisement for this years latest iteration of automotive desire. There is no glitz, no sparkle, no sex appeal. These cars are dead.

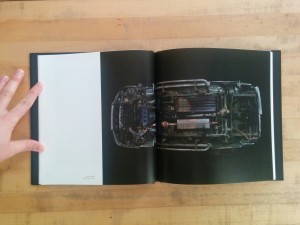

Yoon Seungjun’s Automatic Description is a book of car photographs. These photographs are not your everyday glossy advertisement for this years latest iteration of automotive desire. There is no glitz, no sparkle, no sex appeal. These cars are dead.  Automatic Description is broken into chapters that build one upon the other. The book begins with “Anatomical Chart – appropriation,” a typological series of images of individual car’s under carriages shot against a black ground. These photographs reduce the automobile to its basic structural form, minus wheels. We see the body frame with the suspension structures, transmission, driveshaft, and exhaust systems hanging from it. With their wheels removed and reoriented in space, these automobiles are no longer vehicles but rather abstract forms. Looking closely, one can find narratives in the abstraction: oil leaks, broken drive shafts, scrapes, rust and burn (?) marks. There are stories in these forms however banal they might be.

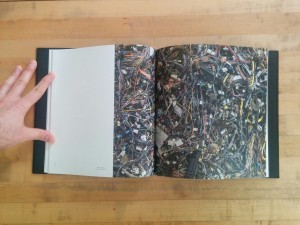

Automatic Description is broken into chapters that build one upon the other. The book begins with “Anatomical Chart – appropriation,” a typological series of images of individual car’s under carriages shot against a black ground. These photographs reduce the automobile to its basic structural form, minus wheels. We see the body frame with the suspension structures, transmission, driveshaft, and exhaust systems hanging from it. With their wheels removed and reoriented in space, these automobiles are no longer vehicles but rather abstract forms. Looking closely, one can find narratives in the abstraction: oil leaks, broken drive shafts, scrapes, rust and burn (?) marks. There are stories in these forms however banal they might be. Chapter two, “Anatomical Chart – combination,” moves from individual vehicles to the aggregation of them. Vehicles are no longer individual stories. Instead, they interlock in stacks and heaps. Crumpled cars are crumpled in a pile. Hundreds of gas tanks are mounded together. Wiring harnesses are enmeshed in a chaotic singular mess. Pipes of every description writhe together like so many snakes in a pit. The singular story has given way to a history of multitudes. Yoon brings his camera in close for these photographs. We see no ground; the subject fills the frame. We are again seeing this automotive wreckage as abstraction.

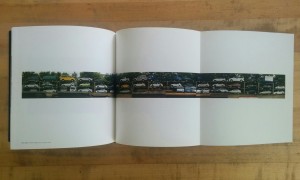

Chapter two, “Anatomical Chart – combination,” moves from individual vehicles to the aggregation of them. Vehicles are no longer individual stories. Instead, they interlock in stacks and heaps. Crumpled cars are crumpled in a pile. Hundreds of gas tanks are mounded together. Wiring harnesses are enmeshed in a chaotic singular mess. Pipes of every description writhe together like so many snakes in a pit. The singular story has given way to a history of multitudes. Yoon brings his camera in close for these photographs. We see no ground; the subject fills the frame. We are again seeing this automotive wreckage as abstraction.  “Scraped Car Chart – parade” is the third chapter and takes us off into the new territory of documentary context. Yoon has pulled back to show us the space in which these cars are resting. We see the rows of racks and risers on which the cars rest. Some of the vehicles are half dismantled; others seem as shiny as new. Sunlight glints off of chrome and polish, still. In the middle of the chapter a gatefold presents a long panoramic image of column after column of junked cars. There are obvious joints in the image; it is not a singular panorama. Yoon has constructed this image–no different than we have constructed this entire infrastructure of disposal (such as it is). Just as the infrastructure of roads, highways and city streets has been built to accommodate the relentless drive of automobile culture so has an infrastructure been built to support the end stage inherent in consumerism. When millions are buying cars, millions are inevitable discarding them as well.

“Scraped Car Chart – parade” is the third chapter and takes us off into the new territory of documentary context. Yoon has pulled back to show us the space in which these cars are resting. We see the rows of racks and risers on which the cars rest. Some of the vehicles are half dismantled; others seem as shiny as new. Sunlight glints off of chrome and polish, still. In the middle of the chapter a gatefold presents a long panoramic image of column after column of junked cars. There are obvious joints in the image; it is not a singular panorama. Yoon has constructed this image–no different than we have constructed this entire infrastructure of disposal (such as it is). Just as the infrastructure of roads, highways and city streets has been built to accommodate the relentless drive of automobile culture so has an infrastructure been built to support the end stage inherent in consumerism. When millions are buying cars, millions are inevitable discarding them as well.