On October 26th, Sangyon Joo of Datz Press came by KPB HQ to talk about her experiences as a publisher, curator and photographer. We’d first met during Printed Matter’s Art Book Fair at PS1 when I stopped by the Datz Press booth. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

On October 26th, Sangyon Joo of Datz Press came by KPB HQ to talk about her experiences as a publisher, curator and photographer. We’d first met during Printed Matter’s Art Book Fair at PS1 when I stopped by the Datz Press booth. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

MNM: Sangyon, thank you so much for making the time to come out to Brooklyn for this conversation. I am delighted to have you here and looking forward to the conversation.

SYJ: This is the fifth issue in our magazine, Gitz. Our conversation reminds me of somebody we profiled in the magazine, a Korean book collector who collects books about Korea. The books he collects were made by Western people who came to Korea in the early years, a hundred years ago. They saw the Korean people and culture and archived their observations in books. They collected and spread exotic cultures in their home countries. He goes to Western bookstores to collect these books about Korea and brings them back to Korea to show to us. It says a lot to me about how books work and how books can go around sharing culture. I think it is a very interesting job mixing Western views of Korea—we can see ourselves through their eyes and can find ourselves through their eyes. Something really great can be done with books.

MM: It’s interesting this idea of seeing Korea through these Western eyes and getting different perspectives. Books like these are oftentimes as much about the culture that they come out of and indirectly describe the culture that produced them as much or more than the culture that they are purportedly about. In a sense, collecting all of those books makes Korea into a constant and allows comparisons of who is saying what and how they are saying it.

SYJ: It is interesting to see all of the different views from inside to outside but also outside to inside. All of this mixing together is how we learn about the world and the arts. It is special to me to do this interview because I know Korean photography and film society very well. I’ve been doing my own work there since my late twenties—almost fifteen years have passed already. After 10 years in Korea art society I left. I went to San Francisco to study because I learned the history of photography as a history of Western photography. I wanted to know what it really means so I decided to study overseas in San Francisco.

I studied photography at HongIk University, where I did graduate studies in photography after getting my under-graduate degree in graphic design from Seoul University. I learned photography through books. That was important for me—I saw all the history and the photos through books rather than through exhibits.

MM: So you’re looking through these books, are they books of Korean photography?

SYJ: No, history books of famous photographers from Europe and the US–not very much Korean photographers’ work. I very much admired the work [of the Western photographers] that I saw and wanted to experience more closely that photography. That is why I chose to study in the US. One of my favorite photographers was Minor White. Minor White was a teacher at the San Francisco Art Institute and there are photo groups that are centered on the School—so Ansel Adams and nature, etc…

I went to the school. I met Linda Connor there, and she acted as my mentor. She saw something in my photography and encouraged my to bring it out. I came to nature photography in the US. I had lived in an apartment in Seoul, so I wasn’t close to nature there. When I moved to San Francisco I was amazed. As a human I was reborn with the nature. I bought a small house. I made a garden. My photography changed greatly. I spent four years after graduating working with Linda. There is a very good photography community there. They were encouraging to one another and organized many lectures and artist talks. I experienced a lot there and feel very blessed. I got inspiration from many people: colleagues, friends and teachers. Four years there made me very rich and happy.

Through that time I started learning how to make books. It’s all connected: my story, my work and Datz Press. I want to show you this first…

This is the first book that I made when I had a show in Korea after my graduate degree. This is just a catalogue for me. I was concerned about the paper and the printing, but at that time, 1999, it was not very common having this kind of catalogue. But, I thought that the show would be gone quickly while the book would remain. As a photographer, I thought it was important to publish a book so that the work would last in a timeless way.

This is the first book that I made when I had a show in Korea after my graduate degree. This is just a catalogue for me. I was concerned about the paper and the printing, but at that time, 1999, it was not very common having this kind of catalogue. But, I thought that the show would be gone quickly while the book would remain. As a photographer, I thought it was important to publish a book so that the work would last in a timeless way.

MM: Was this book through a publisher or self-published?

SYJ: Self published. I made a connection with a very good printing company and made it myself. This next book was made one year later after another solo show at the museum. It is a similar kind of catalogue.

SYJ: Self published. I made a connection with a very good printing company and made it myself. This next book was made one year later after another solo show at the museum. It is a similar kind of catalogue.

MM: This one feels less like a catalogue. It is full bleed…. There are gatefolds…

SYJ: Right, I wanted to make the space into a book. This show was more like an installation. There were 14 pieces on the wall and it was all about space. So I wanted to have a similar feel in the book. This is still a little like a catalogue, but less so. This is from 2000.

After this my work continued to develop. I was interested more in philosophy—my work shifted over these three years. This is work from 2004; I had a show at the Hanmi Museum in Korea. It was a nice opportunity to have a solo at such a young age. I decided to make this book without words. I wanted the images to float. I wanted to make something like music. I designed this book to be about floating—just images without explanation. I wanted somebody to feel what this was about: the fragments from my daily life. From this book on I was very hungry in regards to bookmaking.

This next book was published by Noonbit. It was the first book we did together. I did all of the design and went to the printing company to see the printing went correctly. I was unsatisfied after all of this. It was published in an edition of 1000 copies; Kyusang Lee was very brave to publish this with me.

MM: This is outside the usual style of photography that they publish.

SYJ: I know, but he felt that he could sell these books in 10 years. He thinks in long timeframes. [laughter] If he can sell maybe 500 or 600 it breaks even. So he can wait. He said very positive things about it. I saw our situation as bad at that time. I knew it.

MM: When you say “our situation,” you mean what?

SYJ: As a photographer, making a book and selling it isn’t working well.

MM: You’re not going to make money?

SYJ: No, not at all. As a publisher I admire what [Kyusang]’s doing. He was brave enough to do this kind of experiment with a not so popular young artist.

After we published the book—it was only $15, I saw it in Kyobo. I felt weird. First, I didn’t want this kind of quality. I had wanted to use different paper and…

MM: The paper here is a fairly thin, coated paper.

SYJ: Yes, given the budget they can afford this one. They set the options, and I had to follow them: this coating, this medium. I found a designer at this time who did all the typography, design and everything on the Macintosh computer. I gave [Noonbit] the PDF file, and they changed it into Word files and then published from these. At that time they didn’t have an “art book” mindset. They were more academic.

MM: They don’t make books as objects…

SYJ: No. They are limited to this kind of subject matter and design.

MM: And they’ve taken that idea of keeping their books accessible and affordable to a new level with their recent Collection of Korean Photographers’ Works. They want them to be affordable and accessible in the same way that people can buy paperback novels or poetry. But I can see how the limits necessary in doing so would be frustrating.

SYJ: I was not fully satisfied with the quality. And the book was published in 1000 copies. It was not reasonable, for me at least. This work was valuable for me as a person and as a young artist. I realized later that I should have made this book in a limited edition with only 100 copies and in a very special way. But, at the time I didn’t have any options for that. So, I saw this book at Kyobo and felt very put off. It was very strange there. This was not the way I wanted to make my books. I really questioned, “Is there any other way I can make my books and work in a very consistent way over a long journey?” I knew that my work, when I make photographs, when I make a series my mind is geared towards making a book every time. I am editing and arranging and making a book finally. That is what I want to do with photography. I want to keep making my books.

MM: You realized this before coming to study at the San Francisco Art Institute?

SYJ: I knew it but I didn’t know how. This book was the turning point for me in realizing that I needed to find a new way to show my work. I can go very small editions but want high quality. The book can be my work, the finished piece.

MM: Would you have made that realization or that leap in your work if you had not made this book in this way with Noonbit?

SYJ: I found that my thoughts were clear after making the book in a way that they weren’t before. I didn’t know the difference between making a book of 1000 copies versus 10 copies. After making this book I realized that there should be many ways of bookmaking and that I can find my own way to make it and keep going. Beyond that, I still didn’t know how. At the San Francisco Art Institute I I took a class on artist book making.

MM: Do you remember who taught that class?

SYJ: John DeMerritt. He is a famous book arts figure in the Bay area. He makes all of the famous artists’ books. He was a good teacher, and I very much enjoyed the class. I learned that there was a field of artist books and that I can make my own books in small amounts. That was still not satisfying because the editions were very limited and very expensive. So after that, after I graduated, I found my colleague Ben Zlotkin’s Edition One.

He’s a good friend; we were the same class. He lived in Berkeley, and my house was in Berkeley. So I watched him from the beginning of his small book studio that he started. I went, and we worked together. I worked part time for him for a few months. I really loved it. Just watching him was really amazing. This was one way that I could publish my own books. With the digital offset process we can do whatever: hundreds of copies and right away.

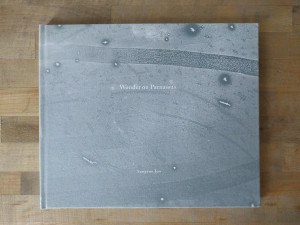

I made this, Wonder of Parnassus; it is the work from my two years in the MFA program. First I made this book with inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle paper and bound with glue and box cases made with John DeMerritt.

MNM: And that’s a lot of work…?

SYJ: Yes, a lot of work. But it was really well made; like an art piece. I exhibited the book at the graduation show, and many people loved it. But, it cost $1000 just to make. So that was just for the show. After, I made two more copies. One I gave to Linda Conner and one I gave to a dear friend and I have one copy. And that was it.

MNM: This book that we’re looking at isn’t that book?

SYJ: No, I made this version with a print on demand system with Ben Zlotkin. I went to his studio, Edition One, with the design I had made. This cover—they had only very limited options at that tim, I printed the covers on my printer and brought all of the covers and made this myself.

SYJ: No, I made this version with a print on demand system with Ben Zlotkin. I went to his studio, Edition One, with the design I had made. This cover—they had only very limited options at that tim, I printed the covers on my printer and brought all of the covers and made this myself.

MNM: So you wrapped the prints on boards and did this all by hand?

SYJ: Yes. And then they printed it and used their binders. I made 50 copies for myself and I have my book published as a result.

MNM: I understand the making process and the thought process of making it this way. What was your intent in terms of distributing this or selling it or sharing it with people? How did that work?

SYJ: I just made it for myself. If I have a show I can then introduce my work through the book and sell the book through the show. That was my wish: to have it as a portfolio for myself. So I made these 50 copies and I knew all the processes. At that point, after four years here, I had to go back to Korea. I felt that I should bring this process to Korea.

MNM: This is 2010?

SYJ: 2010, correct. 2009, in October, I went back to Korea. I had to set up a new place. And then in the spring of the new year, of 2010, I started. I had many friends there. Many were my students or had been my students. I had taught at the University so I had many friends and students and colleagues, photographers and designers. At first 11 people gathered together, and I taught them how to make books.

MNM: Was this a workshop or a class? Through a university?

SYJ: No, we were just groups of people who loved books and photography.

MNM: Do you remember who was in these groups?

SYJ: Most were my students or ex-students. After I had to register as a business to be able to open the book studio. Everything goes so fast. And at the same time it is my personal thing.

My father had a lodge for 30 years. It is a retreat center in the country side. When I went back, my father wanted me to run a small gallery there. He’d begun building one. At that time I didn’t have any idea how it works. I just helped my father build the gallery. So that gallery was… it looks like the San Francisco Art Institute. I designed it with an architect. This was my wish: I got many inspirations from San Francisco Art Institute and I wanted to start something based on my inspiration. So I wanted a small courtyard and pond there. It’s like SFAI.

MNM: It’s a very Spanish-colonial kind of vibe, yeah.

SYJ: It’s odd to have this kind of building in the countryside of Korea, but personally it is very meaningful for me that I started something here and rooted something here from the inspirations and visions I brought back from the Art Institute. At the same time, it was not my intention—the museum—we got permissions as a museum. It’s a very small size, but a big lodge. And we have small book studios in Seoul area. We had to have printers and binders and everything—so my money just went out. [laughter] Everything was really unexpected at that time.

MNM: A lot of learning as you went?

SYJ: Yes, after six months people all left. And new people came in. We had some struggles for a year or two years.

MNM: This is staff leaving?

SYJ: Yes, staff. Eventually they became employees.

MNM: This is the museum and book studio?

SYJ: Correct. I was just an artist and teacher and didn’t know anything about business. That three year period of my life was really kind of dark. I went through a very difficult situation with everything. I was an idealist and visionary.

MNM: The day to day nitty gritty details had to be taken care of…

SYJ: I am really glad that over those three years everything became very concrete and that we got very faithful people back. After three years I started to clearly see some visions of what we are doing. I could make my own book through our press and the artist and photographers in Korea started slowly to notice our existence.

MNM: How did you promote this? Did you reach out to people? Did you have openings or events?

SYJ: We did, but we’re really bad at that. We’re working hard and we’re happy with what we’re doing. It’s hard to be outgoing and to preach what we’re doing; and social things—I’m bad at that. That influenced our business and everything. At that time that’s why I had a struggle with the situations I was working through. I was really sad because I started all of the business because I wanted to do my work but because of the business and museum I had to stop—I almost couldn’t do my work at that period. I was sad, but I had some vision that I was really—I think that what I learned and got inspired from Western photography was really broadened and not focused on some styles or some popular things but its really various. Everybody, each of them doing their own work. It seems abandoned. Abandoned?

MNM: What seems abandoned?

SYJ: The styles and photos by a young generation. Young photographers doing like wet plates and gum prints or digital—60/70 year old photographs are doing digital. It’s all mixed up. The scene is really wide and abandoned and free. I saw that. It’s out of the frame—really wide. You can do anything you want.

MNM: In the West?

SYJ: Yeah. I found that from the community I was part of in the Bay Area. I started to figure out why this culture is so deep and so mature. The art scene of photography seems really inspired to me. In Korea there are certain types of photography that are really getting popular—they had to all go together with one scene.

MNM: That seems to me to be a culture thing in Korea across the spectrum, not just photography. If you look at music or fashion, when something becomes popular everything becomes that. And then something else comes to replace the trend and then that becomes huge.

SYJ: And every small differences and points of view are neglected. They are invisible. For me that’s not the maturity of art. I found that it’s because we don’t have roots and deep history of something classic inside. That’s the kind of fertile ground that we need. I started to see all of the systems behind the artist. One interesting personal story for me was: I had been friends with Josh Partridge, the grandson of Imogen Cunningham. We’d been very good friends and spoke about photography often. I admired the deepness of Western photography. He was a printer of his grandmother’s work. He made beautiful digital and platinum prints of her work. He told me that Imogen had respected Asian cultures and asked why I wasn’t proud of that. I don’t know that we have that kind of richness in our photography culture because in photography history of 160 years, we just have 60 years of photography of photography history. We got photography 100 years after its invention. We got photography not through the West but through the Japanese. Mostly our academic system comes through the Japanese.

MNM: Which creates a whole set of cultural, um, difficulties.

SYJ: Right. That’s what I saw to be the problem. Especially the name: The origin of the word “photography” in English is “light drawing”. In Korean, “사진” [sajin], derives from Chinese characters meaning “copy of looks” or “copy of the thing”. It came through the Japanese language into Korean. It’s a very technical word. I found that from the origin of the word itself the meaning is very different. In Western culture it can be art. We’re just copying something.

MNM: Sure, it emphasizes the mechanical aspect of the medium rather than the art aspect.

SYJ: Many academic courses in Korean schools have the same assumptions. In Korean universities—they have the photography major in technical college not in art school. One of the best art schools in Seoul is Seoul University; they don’t have a photography major.

MNM: HongIk University doesn’t have a photo major?

SYJ: No, they have a graphic design major. Students can learn photography through that, but they don’t have a photography major. There are photography teachers there but they are in the graphic design school. The MFA program just started a photography degree. The tradition of Korean [photography] education starts with a 2 year course at the technical college. They have separate photography schools. That is the basic roots of where photography came from. Very different.

What I learned from SFAI–it is 130 years old, it’s an old art school–SFAI is the first art school to have a photography major in an art school in the US. That tradition is very important. The first professor of photography there was Ansel Adams. That’s the beginning of how photography engaged with art not as a scientific technology or some other aspect. That’s a really different origin. I think these historical directions are made present. I found education, publishing and the galleries—everything influenced photography and artists. I consider that as a ground that has some richness. If the ground is very good, if the artist is a seed than they can grow into big trees. They can become a beautiful forest and art scenery. But, I found that our publishers, in my experience, have some limitations on that. Iann wasn’t there before. And other publishing companies were not focused on photography. There were none.

MNM: Youlhwadang published a few books in the 1980s, and Noonbit told me they were the first focused solely on photography.

SYJ: Right, in a more academic way—not as a visual book as much. They presented very limited possibilities for publishing photography in Korea. I saw many major photography publishing companies, like Nazraeli, Radius and recently Mack. It’s kind of an ideal to me to have those kind of publishers but I couldn’t find any in Korea. So that’s why…

MNM: You started your own.

SYJ: Yeah. That happened. I’m not sure that I can be an influence in Korean photography or society. I didn’t have any big vision for that; just for me.

MNM: Did you have a plan when you were starting it? How did starting it happen? What did starting it look like?

SYJ: It wasn’t planned very well. I was just following my own path: what I need and what I want and what I can do. Is there anyone who can do this together with me? And we just gathered together. I just knew we needed this kind of thing. If I wanted to go back to Korea and keep working, if I don’t want to just wander around looking for who can show my work; I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to create a long marathon like career for my whole life. If I wanted to do that I needed to be able to do my own books myself.

MNM: Create the structure where you can make work, publish work…

SYJ: If I’m not showing my work very often at least I can make my own books and keep going. That was my non-aggressive way of making my own work. That’s how it started. Through the museum and through the book I was trying to find the right content. Some photographers came by and wanted to publish their own work through us. But, I think there is particular content that is right for photography books. Some works are more about words; some can be just a catalog. As a photo book it can be the gathering of thoughts and scenes and vision and stories and more; and you have to create more space.

MNM: There has to be a reason for it to be a book. What it is that makes a book worthwhile for Datz? What is it that makes a project interesting for you as a publisher and that makes it right to do a book with you?

SYJ: It should be more than three dimensional. A photo itself is 2 dimensional. It can reach deeper meanings, but it is two dimensional. Gathering all the images together is like a novel or writing of a whole book. It can incorporate time and concepts and philosophical thinking, process and space and everything. It can be more, can be beyond time and space through the structures in it. I want to make interesting content. I think book making is like architecture. It’s like building a house. We can assume things about the people who are in it and their life and we can see and read and hear the stories. I want sequencing—the photo is like one jewel in a necklace…

MNM: ..being strung together…

SYJ: Yes. All is connected with the sequences and everything can be one whole, one connection.

MNM: That’s an interesting metaphor: stringing jewels together in a necklace. At least in the three Datz books that I have (your Grace and Gravity, Younghae Kim’s A Scenery of Consolation and Yoonjean Lee’s Still-Life), there’s this emotional, almost musical thread that runs through them and ties them together. Each photograph is rich and colorful, sort of jewel like. They seem to be almost the opposite of, say, documentary work. Is that abstractness something that is important for you, or is that a misread on my part from only seeing so many books?

SYJ: I think that is only seeing those three Datz Books [laughter]. I am pretty open with other kinds of contents including documentary. In my library, like my brain, there are different kinds of interests that I have in many different kinds of photography. It is very broad, and I don’t have any preference of specific styles or specific roles for photography.

MNM: Is there anything that guides your decision, besides it being good photographs that are more than just themselves. Beyond that, what is it that you look for in a project? What is it that your goal is with the press; what’s the mission and the intent for your publishing program?

SYJ: I want to have the very classic and traditional work alongside very new and fresh contemporary work. I don’t prefer any styles or any other things. I don’t like to show just beautiful images with photo books–I’m searching for values and meanings and good and beauty and truth all together. I don’t think there are any answers or any one way that can be reached. Right now we’re working with very limited hands.

MNM: How many hands are at Datz Press? Is it just you? two of you? three of you?

SYJ: No! No! I will just initiate and gather all the projects.

MNM: You’re the executive?

SYJ: Yes. I say, “Let’s do this” and there are trusted expert book makers working, too. At Datz Press there are three people. They are in their twenties and thirties and really into it.

MNM: Do you want to give them a shout out?

SYJ: Oh, yeah: Juyoung Jung is the producer and manager. Jeongin Kim is project manager. Yonghae Kim is a designer and bookmaker. At the Museum there is Jinyoung Park, Sungju Youn and Hang-A Kim

MNM: …And also you’ve published Yonghae’s work.

SYJ: Yeah, this is what I intended to do before. I really liked the system of Edition One. After he started his business, graduate students who graduated from the SFAI MFA Photo Program all wanted to work there because they are artists and they really wanted a job. It was an ideal place for artists who loved books to work. So I saw that and as I taught many students I thought about how they would become artists. We needed good jobs for artists so that they can keep going with their work. Datz Press can be an ideal place [for artists].

MNM: So it’s a jobs program also?

SYJ: Yeah. Artists can work there and we can share many inspirations together. So those three young women are also photographers and designers. They are doing their own work as well. That’s really ideal and makes me happy right now: that I can offer that place and those jobs to them to be able to keep going with their work.

MNM: You noted that they are “three young women;” is it important also to give opportunities to women in the art scene—broadly or specifically in Korea? Is that an important factor or is it just happenstance that it is that way?

SYJ: Just happened. But there’s not so many opportunities—the same for men or women. It doesn’t matter. There’s not so many opportunities for artists who can survive. So I think it’s a great place for work as an emerging artist, having their daily routine.

MNM: And seeing art and being involved, but also…

SYJ: They can grow together.

MNM: …of being involved in the process of having to make things. I think when I was younger, and I’m not sure I’m over this yet, but I think there was a definite disconnect in terms of the thinking about making work and the making of work and then the finishing of work.

SYJ: Yup. [laughter] Each of us are providing good influences for one another. This is ideal so they can keep going. Isolated young artists are struggling and having difficylty being alone. We have three more people at the Museum, the two curators and one as a workshop manager. So we are, altogether including me, seven people working right now.

MNM: What kind of workshops are you running at the museum?

SYJ: I value handwork, something very physically involved. I think the way physical labor goes together with efforts in the brain makes everything very strong. It is important to have some balance. So we have a book making class, clay workshops and also a carpentry class.

MNM: Are these aimed at artists or at lay people?

SYJ: It’s open to the public, anyone can be involved with the workshops. We have many workshop programs available.

MNM: Where is the museum?

SYJ: Gyeongi-do, it’s about 45 minutes drive from Seoul. It’s not that far but it doesn’t have any transportation besides private cars. I think that is a weak point, but it’s kind of an opportunities that we can do whatever we want. I think of this as a very positive situation. I began to make connections between publishing and exhibitions. The exhibition is time limited and then it’s gone. The physical space is far away. But, we can manage that with publications. If we archive that show with a book then we can show this everywhere.

MNM: Is every book tied to a show?

SYJ: Yes.

We are planning one major show together with this magazine. With previous issues also we had related shows. We brought this work from here and some archives from Hakyong Cha’s work and we showed all the book collection in the show.

It is very important, for me, to have connections with the Western Arts—to create a mixing together. So I found interesting artists here and brought their work to Korea; and, I am making books and bringing those here. In two weeks I’m going back to Korea with the work of Barbara Bosworth, who lives in Boston and teaches at Mass Arts, and Stefan Tourlentes, who also teaches at Mass Arts. I am bringing these two artists’ work together with that of three painters from Korea. We are curating Korean artists and US artists who I can reach easily while here [“Here” being NYC where Sangyon is temporarily based part-time]. We make books and then bring them here. So far it is going really well. The beginning of this was Linda Connor visiting Korea to see the museum.

MNM: You published a book of hers I saw.

SYJ: Yes. Of course. That was maybe three years ago. She helped me to arrange the artist show with Bay Area artists with Chris McCaw, Klea McKenna, and Ben Nixon. They were good friends of mine at that point so I brought that work to Korea and showed it. That was kind of new to Korean photo society. We were very focused on very famous Western photographers—none of the middle class artists. So I brought new content and held artists’ talks and workshops. We had for the first time a wet plate collodion workshop with Ben Zlotkin. I brought him to Korea. That kind of trial made me very brave. That kind of thing was, from the beginning, step by step. And now I’m here.

MNM: How important is cultural exchange for the Datz Press projects?

SYJ: I think it is kind of a window for us to see what is out there. If we can open the window we can get fresh air from outside. That really opens us to new visions, and I want to be a conduit for fresh air. I really admire the richness of the Western photography scene. I am happy that I can open some small window through Datz Press and a small museum space and this magazine and other publications. Half of our publications are of Western artists’s work. They really loved our process and quality of books. They’re all artists I know; they respect what we’re doing, and I respect their work. For example: Barbara Bosworth’s work, 30 years of work, she has been working in a very steady way over a really long period. Linda Connor’s work–she has been photographing the same way for forty years… It’s very steady and very classy. In Korean eyes it isn’t very new or fresh, but it is classic. And the work is very powerful. I want to show that to the Korean audience. I don’t think they know all the different kinds of middle class artists who are working so hard like this. They know only Michael Kenna or something very popular. I am very inspired by the middle class, steady, working artist whose lives are very devoted to their own work, their own way. I think they are very valuable. If I find someone like that I wish I could make books of their work.

MNM: You’re talking about the exchange, of bringing the fresh air of mid-level Western photographers to Korea, and providing a window on their work. Does the window work the other way? Do you have any goals of bringing Korean artists to the West?

SYJ: Of course. Of course. Of course. I think it’s not ready yet. We’re not ready yet. It’s more for the future. I want to introduce many good Korean photographers to the Western society. But I have found limitations because of our system.

MNM: Well, when you’re printing ten copies…it’s hard to send even five of them out.

SYJ: Yes, but we’re studying using offset printing. My book is 300 copies via offset because every time we decided the amount it is connected with the budgets. If artists can provide the budget than we can make it bigger with more options. But at this time in Korea people don’t buy books.

MNM: Did you sell many books at the Arts Book Fair?

SYJ: I sold through the Book Fair more than I sold in five years in Korea.

MNM: So, it was successful then.

SYJ: Yeah. [laughter] It was amazing.

MNM: And your books are not the cheapest books. I mean if someone is going to buy books…

SYJ: Even though our books are expensive, I was really surprised that there were so many more viewers and customers here than in Korea. I was really surprised. I mean, we make money but the way we can make money is through orders of print on demand projects from outside customers.

MNM: You’re also providing printing services?

SYJ: Yes, book making services for their own work. These aren’t our own publications.

MNM: You just make them… like Edition One?

SYJ: Right. Without that we can’t survive.

MNM: Your print quality is beautiful, the material quality is beautiful, the workmanship is beautiful. That’s what makes one of your books one of your books. Is that fair to say?

SYJ: Of course our prices is a little bit higher than Edition One or Blurb because our materials and other options and design service makes them really custom books.

We are focused on very small details in materials and the book itself and how it feels and how it looks. Everything goes with the content and we try very hard to develop our skills and process. We don’t mind some experimental trials. We go really custom.

I know Ben Zlotkin very well. He’s very energetic and very smart and very savvy as a businessman. He’s very focused on profit and really making it work as a business.

MNM: Sure. There’s nothing wrong with that

SYJ: No; I wish I could be like him. We know our differences. Linda Connor is a really close friend with Ben Zlotkin as well. He knows both of us. Linda always says, “Ben why don’t you use the paper Sangyon is using?” And he’ll reply “Nope, our machine is not working well with those kinds of papers.” So he keeps working with an original Xerox machine paper, so that reduces his risk of wasting of paper. His focus is really clear with every option. If he has many different options with book cloth and bindings it makes the business slow. Many options make it difficult. We do the very opposite way. We welcome many possibilities; and there are many materials we want to try. We suggest very high quality materials to customers. Every time we go for a very new development. That makes us happy. Maybe that’s a very different part of it but that’s why we don’t make money very well. We just keep going. That’s the only reason we really want to do it: for our satisfaction. Money doesn’t make us satisfied for now. Because of that we need to be happy with the quality, meaning and values that represent. I think I was really confused with each step about where should I go. Am I ok with this–business wise, money wise and everything. Right now I can make it even.

We want to keep the people and keep the size. We don’t want to expand everything. We need to keep our quality and keep going forward focused on valuable content. That is our strategy. Maybe it’s not a very smart strategy. [laughter] I think of our business more as an adventure. It’s not clearly smart.

MNM: You never know what’s going to work. Experimental seems like a perfectly reasonable way to go about it. That’s how I run my business.

SYJ: That’s why I respect you through your blog. You’re having your own path, developing your own way. I think you also are really strange because Korean photography books don’t seem very interesting to me. It doesn’t have any deep historical basis or contents so I think you’re really in a new field you can develop.

MNM: Well, that’s what seems fascinating to me: watching it. There’s such a huge history of the photo book going back to the beginning of the history of photography with folios and tipping in photos to books. Through the whole history of photography the photo book is always there. When I first starting buying the Korean photo books I kept thinking, “It’s just like any other photobook.” But then I started realizing that it’s a decade or two decades behind in the development of the photo book but its amazing, even over the last ten years of collecting them, seeing that there’s so many more publishers and so many books being published. The growth is exponential. It’s really fun.

I was recently writing about Taewon Jang’s latest book, looking at his photographs of industrial sites in Korea, Japan and America taken at night. They brought to mind Mitch Epstein’s American Power and Will Steacy’s Down These Mean Streets; two American photographs shooting the American power industry or shooting at night. Looking at how different photographers from different cultures or different generations view similar topic matters differently can make the cultural assumptions we all carry evident. And then it takes on a life of its own.

SYJ: Yeah, one can reflect other cultures through your culture. You can develop your own identity as well.

MNM: You were talking about the collector of books about Korea and through that collection of books seeing how the West views Korea. Well, it’s fascinating looking at the work of numerous Korean photographers and you get a sense of how Korean culture views everything, too.

SYJ: It was really fresh for me. I can say about my crew is that they are really isolated in Korea. When we came here for the book fair I found many in the book society here who were more encouraging and shared more feedback.

Back in Korea we don’t have any community of photo book makers; we don’t have many people to share ideas about Korean photo books. I think we are very limited to ourselves there. Sometimes we really want to hear feedback. I think we’re starting really new things. Five years ago, still, people were asking “Are you running a business?” and “Is it work?”. I still get many questions and worries about that. So, participating in this New York fair with my two staff who came and just watching so many people be interested in our books, and seeing you, who collects Korean photo books, makes us really happy that we can connect with like minded people all around the world if we do our work in a good way. So, we have hope right now. We are very positive after the fair.

MNM: Changing direction: you talk about all of this work and how much time it all takes; are you still making your own work?

SYJ: Yes. Of Course, For the first three years I couldn’t do any of my work, but with Grace and Gravity I’ve finally been able to arrange all of the works done in the Bay Area and make that book possible through Datz Press. That’s very personally meaningful.

MNM: So it comes back. The press came out of things you were seeing as being needed by other artists and now allows you to put that together.

SYJ: Yeah, that’s a positive sign for me as an artist. Right now I’m still working on landscape photography on the West Coast here and also landscapes of Korean lands. This is the work I am doing now, I had a show last year.

MNM: And you made a book of course.

SYJ: Yes. So, this is for you.

MNM: Oh, thank you.

SYJ: This is the work I’ve done in Korean landscape over the past two years.

MNM: And this is through Datz?

SYJ: Of course. [laughter]

MNM: Where was the show?

SYJ: Gagarin; it has a gallery at the back side of the building. It’s a traditional Korean hanok. I really like the space there. This show was originally arranged as a photo book show (for myself), it is a small space divided into three. So I made an installation with my book arts.

I found the new sceneries in Korea when I came back. So that’s how I re-approached the Korean landscape. I’m still doing this work. I started a project at Walden Pond as well.

MNM: Are you shooting in NYC? I mean you’re spending a lot of time here.

SYJ: A little bit, but I’m not very into the people or cities. I’m still searching.

MNM: It’s interesting this work, Light on Ground, and Grace and Gravity—the thought of a pull towards the ground. You keep talking about fertile ground and the essay in the book talks about fertile ground—it’s keeps coming back to the Earth and being grounded, tied to the land.

SYJ: You can see my history of work. My mind process. This is about the air and water. This is about earth, water, sky, wind. My work is really going through a thought process. After I made this show, Walks on Water, then the next, Wonder on Parnassus was about more airy thoughts. I was there; I was not rooted in that scenery.

MNM: You talked about “floating” in that one.

SYJ: Yes, floating. It’s kind of momentary airy things. After I went through the process I found that I needed to get along with the ground, the world I am in while I am living with my body. This was the last part of earth. I am still struggling with the earth, the body and physical parts. My thought process is a very physical presence for me struggling with the earth where I’m born. I made physical gardens there and the museum—spaces. People are there struggling day by day.

Do you know the meaning of”Datz”? “Datz” is, in Korean, an “anchor”, like roots: deep inside, not moving and strong; like faith inside; like roots of a tree. This magazine, “Gitz”, is, in Korean, feather—and also a kind of inspiration. It’s airier, lighter things that we can share and spread. All of the controversial images are together and combine in harmony. I think it’s kind of the order of this world—two controversial things: light and shadow…

MNM: The pull up and the pull down?

SYJ: I pursue one thing, not very earthly but not very feather-like. I think it all should be gathered and made into rhythms and harmonies. I think that’s life. All these concepts have symbolic meanings. Through my gardens in my backyard I was struggling with the happiness of the earth. I found the plants growing—I couldn’t control them. They’re there and naturally having their own life their own way. I was just watching that, nourished by and enjoying being there. Even if it isn’t the right scene in my perspective. Sometimes I had to just let it be. All those kinds of experiences made me start Datz Press. Where are my roots? Where should I start? So I came back and started to put all these things together. Let’s go back to Josh Partridge’s words: he said to me that Imogen Cunningham had great respect for Asian culture and philosophy and he said also that paper and inks are deep deep in the cultures of Asian art. We have used them since a long time ago. We have an art culture with paper and inks.

So when I was saying to him that Western photography is a hundred and fifty years old but that we only have sixty and that we don’t have a good enough history, he reminded me: The black and white, silver gelatin darkroom is only 100 years old; right now we are going into digital ink jet prints: ink on paper. That, he said, connects with the tradition going a thousand years back. It’s all paper. You have your own tradition there. Look at your oral history.

That thought was inspiring to me. I know that Korean history has something really sad about it. We have 500 years of the Chosun Dynasty. It was very rich in arts and culture, but because of the Japanese colonial period and right after that the Korean war–and we’re still divided into two parts, with all that was destroyed and all the disasters we built a quick society—economically, politically. It’s developed very fast. Right now we have time to look at the past and what happened. We’ve been through a difficult period but we still have hope because we have a long history before that. Maybe we can reconnect with all of the history that we had before and get our roots from that. Maybe that will make our fertile ground more abundant. That’s what I’m thinking and what my conclusion is after all: let me do what I can do and let me do my job as an artist, as a bookmaker and as a museum curator. Maybe after another ten years Datz Press will be one of the first catalysts of the field of photography books if we keep doing our work. I hope that scene can be nurtured for the next generation of bookmakers and photographers and students.

MNM: Thank you so much for making time to speak to me. I really appreciate it.

SYJ: Thank you for listening.