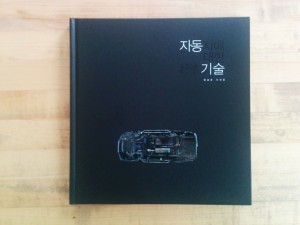

Yoon Seungjun’s Automatic Description is a book of car photographs. These photographs are not your everyday glossy advertisement for this years latest iteration of automotive desire. There is no glitz, no sparkle, no sex appeal. These cars are dead.

Yoon Seungjun’s Automatic Description is a book of car photographs. These photographs are not your everyday glossy advertisement for this years latest iteration of automotive desire. There is no glitz, no sparkle, no sex appeal. These cars are dead.

These cars are literally dead. Yoon has photographed junked junkers in junkyards. It would be a mistake to label this as ruin porn and set it aside with disdain. Yoon’s working method is more in line with the socially conscious impulses of Sebastião Salgado or Edward Burtynsky, though without Salgado’s humanity or Burtyksky’s grand scale. His photography is a critical examination of “the space and environment of modern society,” here that is specifically the junkyard behind the façade of contemporary automobile culture in South Korea. If it also happens to be visually arresting and aesthetically appealing so much the better.

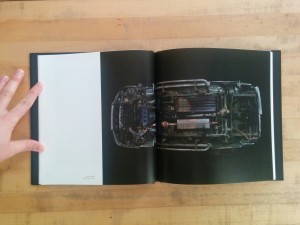

Automatic Description is broken into chapters that build one upon the other. The book begins with “Anatomical Chart – appropriation,” a typological series of images of individual car’s under carriages shot against a black ground. These photographs reduce the automobile to its basic structural form, minus wheels. We see the body frame with the suspension structures, transmission, driveshaft, and exhaust systems hanging from it. With their wheels removed and reoriented in space, these automobiles are no longer vehicles but rather abstract forms. Looking closely, one can find narratives in the abstraction: oil leaks, broken drive shafts, scrapes, rust and burn (?) marks. There are stories in these forms however banal they might be.

Automatic Description is broken into chapters that build one upon the other. The book begins with “Anatomical Chart – appropriation,” a typological series of images of individual car’s under carriages shot against a black ground. These photographs reduce the automobile to its basic structural form, minus wheels. We see the body frame with the suspension structures, transmission, driveshaft, and exhaust systems hanging from it. With their wheels removed and reoriented in space, these automobiles are no longer vehicles but rather abstract forms. Looking closely, one can find narratives in the abstraction: oil leaks, broken drive shafts, scrapes, rust and burn (?) marks. There are stories in these forms however banal they might be.

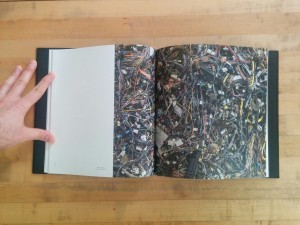

Chapter two, “Anatomical Chart – combination,” moves from individual vehicles to the aggregation of them. Vehicles are no longer individual stories. Instead, they interlock in stacks and heaps. Crumpled cars are crumpled in a pile. Hundreds of gas tanks are mounded together. Wiring harnesses are enmeshed in a chaotic singular mess. Pipes of every description writhe together like so many snakes in a pit. The singular story has given way to a history of multitudes. Yoon brings his camera in close for these photographs. We see no ground; the subject fills the frame. We are again seeing this automotive wreckage as abstraction.

Chapter two, “Anatomical Chart – combination,” moves from individual vehicles to the aggregation of them. Vehicles are no longer individual stories. Instead, they interlock in stacks and heaps. Crumpled cars are crumpled in a pile. Hundreds of gas tanks are mounded together. Wiring harnesses are enmeshed in a chaotic singular mess. Pipes of every description writhe together like so many snakes in a pit. The singular story has given way to a history of multitudes. Yoon brings his camera in close for these photographs. We see no ground; the subject fills the frame. We are again seeing this automotive wreckage as abstraction.

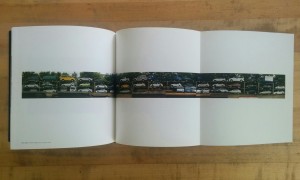

“Scraped Car Chart – parade” is the third chapter and takes us off into the new territory of documentary context. Yoon has pulled back to show us the space in which these cars are resting. We see the rows of racks and risers on which the cars rest. Some of the vehicles are half dismantled; others seem as shiny as new. Sunlight glints off of chrome and polish, still. In the middle of the chapter a gatefold presents a long panoramic image of column after column of junked cars. There are obvious joints in the image; it is not a singular panorama. Yoon has constructed this image–no different than we have constructed this entire infrastructure of disposal (such as it is). Just as the infrastructure of roads, highways and city streets has been built to accommodate the relentless drive of automobile culture so has an infrastructure been built to support the end stage inherent in consumerism. When millions are buying cars, millions are inevitable discarding them as well.

“Scraped Car Chart – parade” is the third chapter and takes us off into the new territory of documentary context. Yoon has pulled back to show us the space in which these cars are resting. We see the rows of racks and risers on which the cars rest. Some of the vehicles are half dismantled; others seem as shiny as new. Sunlight glints off of chrome and polish, still. In the middle of the chapter a gatefold presents a long panoramic image of column after column of junked cars. There are obvious joints in the image; it is not a singular panorama. Yoon has constructed this image–no different than we have constructed this entire infrastructure of disposal (such as it is). Just as the infrastructure of roads, highways and city streets has been built to accommodate the relentless drive of automobile culture so has an infrastructure been built to support the end stage inherent in consumerism. When millions are buying cars, millions are inevitable discarding them as well.

Yoon pulls back, once again, in the last chapter, “Scrapped Car Chart – Goryeojang.” Goryeojang refers to a historical custom in the Goryeo period of taking one’s elderly parents into the mountains and leaving them there to die. There was a movie with this title as well in the early 1960’s in which a son takes his mother to the mountains but breaks the custom by returning home with her. The photographs in this chapter are of cars junked in quasi-wild places. Cherry blossoms bloom above one wrecked SUV. A tangle of scrubby bushes grows up through a bright red wreck of a coupe. A luxury sedan has settled into repose on a hillside; it is surrounded by leafless trees of brownest autumn. A white SUV sits upended into a ditch; we see only its tail end with barren trees towering above it. In the chapter’s final photograph the wrecked hulks of a Bongo and Porter intermingle in the background; they are nearly obscured by the thick tangle of branches and new buds in which they have become buried. The organized infrastructure of the preceding chapter is nowhere to be seen. Instead, automobile culture has intruded upon nature. This intrusion marks a breakdown in order that, perhaps, signifies a culture losing its traction and sliding out of control.

As a member of the photography collective Dream Flower Factory (mentioned here), Yoon shares the collective’s socially minded conscious. This conscious is evident in these photographs. Yoon lures us in with the abstract beauty of the first chapters but is never himself seduced. The title of the fourth chapter makes his concerns crystal clear. Not only are we uncomfortable with the custom he references, but we then must transfer this discomfort to our car culture. We no longer leave our elders in the mountains to die; perhaps one day we will no longer leave our vehicular refuse in the woods to rust away either. If this comes to pass, it will not be a kindness to our elders that drives us, but instead a kindness to future generations.

Automatic Description

Yoon Seungjun

Publisher: Park Seonsoon

Published by: Photodot

July 1, 2014

Photo Edited by: Yoon Seungjun & Choi Yeonha

Written by: Choi Yeonha

Translation to English: Jaeeun Kwak & Grace Yoon

Designed by: Han Jeongyeon

Printed by DaeHyun Printing & Publishing