After interviewing the crew at Corners, Jimin and I took a cab over to The Book Society. During the brief taxi ride I tried to describe what made a book interesting to me. The essentials of my explanation was that I liked highly idiosyncratic personal photographic visions published in object like book form. At The Book Society, she pulled a small volume off of the small publishers and self-published shelf and, holding it out, said, “I think you’ll like this one.”

Continue reading

Category Archives: Landscape

Blocks, Chanmin Park

Every time that I have gone to Korea I have been absolutely astounded by the pace and the sheer volume of hi-rise apartment construction. While most of this astonishment has been a general sense of enormity suggested by the breadth of this construction, over my last several visits I have been able to watch one particular development being built across from my mother in law’s apartment complex. What was once a small tangle of streets forming a neighborhood is now a construction site from which half a dozen towers are rising. (Alan, the post office from which we sent the DIY first issue letter is now gone and its postmark now rare, if not valuable.) This development sits directly between two existing developments and within spitting distance of at least three other new developments.

Continue reading

A Forest Three Meters Squared, Yuri An

As the youngest descendant of all dying things

I

am here.

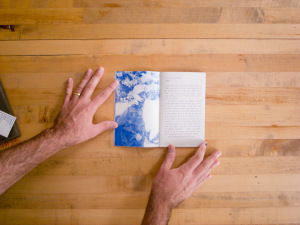

This is the last line from Yuri An’s poem “I Will, I Was / For My Death” and an apt summation of A Forest Three Meters Squared. The poems and photographs in the book are heavy with worry. An anxiety is pervasive–and yet there is also hopeful desire and affirmative longing.

The photographs worry at the edges of the quotidian and find dark images beneath the surface. A dark dock stretches out into a lake, the light in the sky reaching down in a delta shape echoing and refuting the darkness of the dock. A dark frame with an circular image fragment at its center, below it a sunset with the circular fragment missing from its center. A tangle of dense greenery bursting forward. The mottled reflection of light on water, a dark band of shadow cutting across it. The red moon hangs in a dark sky partly obscured by tree branches. A plane screams across the sky leaving a dark contrail to trace its path inevitably bound to dissipate and disappear. All the images underscored with the tessellated jaggedness of a video grab–suggestion of a continuity interrupted.

The photographs sit at the book’s center. From one direction the poetry can be read in Korean. Flip the book over and from the opposite direction the poetry can be read in English. Either way, one ends at the photographs in the center. At the center is the visual image.

An asks in the book’s preface, “when all people shared the same language did they understand each other? Did they share the same dream?” Living in a strange place, away from home and distanced by language, An’s fears spring from opportunity and possibility as much as from strangeness. Complete homogeneity no more guarantees intimacy than does the foreign guarantee alienation. A shared language is not understanding. An image shared is not an idea conveyed. A memory shared is not forever; how does the tree share your secret?

From “Irreconcilable Time,” the first poem in the book:

For some time, I

have locked up time

instilled your memories in my room

Sealed traces, airtight

Living moments, captured, freshly picked

What you and I exchanged

breath

air

I can’t say that I understand the poems (that is as likely my own failing as any issue with the translation) or that I have understood the book’s particulars. I do understand the longing and the fear. I have my own room in which I seal traces. The moments once living, once freshly picked, now captured. But, they’ll be gone soon enough.

A Forest Three Meters Squared

Written, photographed and designed by An (email)

2012

Proofread by:

Kyoung mee choi (sic)

Eunsoo Lee

Jinah Lee

Andrew McCullough

Noga Harel

Production: Gerrit Rietveld Academie

In Between, Taeyoung Kang

As usual, I returned from Seoul with a suitcase full of books. Because of my limited time for browsing for books during my brief trips, I generally err on the side of caution and buy a book if I see some detail that I think bodes well: a design flourish, a single image that catches my eye, a weight or density. This generally works well for me. Sometimes it doesn’t.

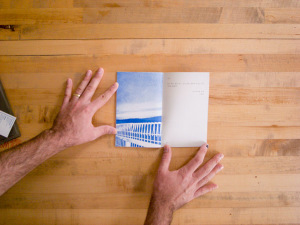

Taeyoung Kang’s In Between is full of promise. The simple and distinctive Aprilsnow Press’ cover design with a photo tipped into the bright red linen is an opening salvo. It calls out from the book shelf. On a cursory glance through, there are numerous wonderfully composed and engaging photographs.

A WB Yeats quote from “Sailing to Byzantium” sets the book’s tone: “Whatever is begotten, born and dies.” The first several pictures take this cue and run with it. The first picture is two empty shell sitting beside several small plants in loose soil; the caption tells us this is in a cemetery. It is followed by a pair of landscapes of the tombs in Gyung-ju; in the first, two boys wearing white back to back stepping away from one another as though dueling; in the second, picture there is only one boy, crouching. The next picture is a boy playing in a ruin; he appears to levitate off the ground, his head poking into a window in the ruin. From this strange and slightly unsettling opening, the book begins to wander.

The wandering is literal and figurative. We are brought to France, back to Korea, then on to Mauritius, Switzerland, Hong Kong, the US, Turkey, Jordan, Italy, Germany, Syria and England. All are revisited throughout the book. It is a whirlwind world tour of the everyday: street scenes, still life vignettes, grand landscapes and portraits.

Though we may travel the world, we are not among a family of man. This is not some grand statement of unity. Instead we are in a space of “between-ness”. In our shifting location we are never “here”; we are always moving between. The photographs hover between light and dark: a young girl on the edge of a pool of light steps out into the dark surround; a boy hides behind a lamp post’s silhouette before a luminous background of dirt; a man directly under a light in a restaurant covers his face; a young woman at a bar sits in a pool of light looking out at the crowd surrounding her recede into darkness. We are often divided from the subjects we view: they are half hidden by other objects in the scene; they are partly erased by reflections in glass; or they are covered by shadow. Or the we catch a moment between moments: a pair of people in mid-step, their weight neither still on the top step or yet on the bottom step; a man leaning over to lift a brazier of coals, his hand pulling on its handle but not yet taking its weight.

This is a book that I wanted to like it and expected to. There are many lovely images and as an object the book is nicely designed, printed and put together. It looks great on my book shelf. Any number of the photographs would look wonderful framed on the wall. However, the wandering is too great. We cover too much territory. A third of the images could have been left on the editing table. Flipping through the book too many images pull me from the rhythm and disrupt the flow. I can’t find reason for transitions between images; I’m not sure what I am meant to come to understand through reading this book.

In Between

Taeyoung Kang

with text by Kay Jun

Edited and Designed by Kay Jun, Jeong Jae-wan

Proofread by Kang Young-gyu

Translated by Angelina Gieun Lee

Printed by Munsung Printing

Published by Aprilsnow Press

First edition January 2013

The Tedious Landscape II, Kim Yunho

Workroom does good design. Every photobook I’ve come across that was designed by them feels right. Kim Yunho’s The Tedious Landscape is from Workroom’s Lájka Series. In Korean, the name reads phonetically as “Lah Ee Ca Series”; Leica Series. I’m not sure how or why it has re-transliterated to “Lajka.” Odd.

Moving on.

The Tedious Landscape II is, as might be obvious, the second in a series of projects. In The Tedious Landscape, Kim explored the outskirts. What does the country look like outside of the major cities?

The photographs in this book are of pageants, which often have the underlying goal of celebrating and promoting local specialty products. As most of these products are natural products or produce, these pageants tend to be put on in more rural regions or smaller towns or villages. As Kim Kyewon notes in the essay that closes the book, “Major cities do not have particular specialty products, and if they did, they would not need to promote them in such a way.” The Tedious Landscape II, then, extends Kim’s exploration of the periphery.

Another astute observation in Kim Kyewon’s essay is that though these photographs are of beauty pageants (whether the contestants are female, male, old or young), there are no beauties in the photographs. The scenes are photographed from a distance. In each, there is the whole stage filled with the full complement of contestants as well as other participants in the pageants–judges, audience members, photographers and assorted hangers-on. There is little action; the contestants in most of the photographs seem to be simply standing there, waiting.

In an earlier post, I spoke about the challenge of writing about work that I can’t fully understand as an outsider. There will always be aspects that are not apparent to me. An essay like Kim Kyewon’s can be invaluable in coming to a more complete understanding of a photographer’s intentions. I note this because I am going to steal (but attribute) an idea from Kim’s essay that is important to the work but that I would not have come up with myself.

The goal of these pageants is to promote the local specialty good. The contestants become double symbols not only as the most beautiful but also as a stand in for the local product. The pageant winners from one region are indistinguishable from the pageant winner from the next region. “The form in which they serve as symbols is repeated nationwide and results in a tedious [landscape].” (Kim uses the word “destiny” here, but as he earlier invoked the idea of topography, I think “landscape” is more appropriate.)

While in total the photographs may describe a tedious landscape, the individual images are rich with cultural detail, daily life and comedy. One of my favorite images is 395-800: 16 women stand on a rain slicked stage, one of them is speaking at the microphone, the others are standing in near identical poses and watching with a smile. The audience is hidden by their scrum of umbrellas. In another image, #355-601, 10 bodybuilders stand around on stage while a photographer and video crew record the winner being awarded his trophy. The non-winners stand around more or less awkwardly; the scene has ended but they’ve not been released from it yet. The audience here is only an ajashi with a camera and a handful of children fascinated by the spectacle before them. In #534-801 the audience is again huddled in the rain, this time wearing ponchos. On stage, six older women stand before drums as part of a traditional performance; a photographer crouches stage right. The front of the stage is draped with a mural of a field of flowers; at the image’s horizon line we are suddenly onto the stage. The top of the frame is kaleidoscopic tumble of lights, trusses and risers.

The book itself is roughly octavo sized, perfect bound with plain board covers glued front, rear and on the spine, and with a 3/4 height dust jacket with a panoramic image that wraps the book (technically this might be a belly band, but it feels more like a short dust jacket). The pages are heavyweight, nearly cardstock, which combined with the perfect binding allows them to lay flat but puts stress on the binding. The layouts are a mix of paired images across from one another and double truck spreads. Both layouts push the images right to the top where they bleed off of the page. Kyewon Kim’s essay comes after the plates and is on a different lighter paper stock. It is in both Korean and English. After the essay comes a list of plates and the artist’s C.V..

This is a tightly designed book of well considered and well made photographs. The clear and concise essay that gives context and added meaning to the photographs is a welcome bonus.

The Tedious Landscape II

Kim Yunho

Published by workroom press

Edited and Designed by workroom

Essay by Kim Kyewon

Translation by Kim Jeimin

First published 1 August 2008

Printed in Korea

Five Views From Korea @ Noorderlicht Photo Gallery

The Noorderlicht Photogallery will be showing Five Views from Korea February 8th through April 13th. Work from Seung Woo Back, Jaegu Kang, Insook Kim, Suntag Noh and Xuezhe Shen is brought together to examine “the discomfort and nagging feeling of an unending cold war since the division of the Korean peninsula.”

From Guest Curator Sujong Song:

Every day, the papers are flooded with news heralding tension on the Korean Peninsula. Perhaps because they are in the eye of the storm, but the people living in the southern half are largely skeptical of an outbreak of war. The feeling closest to fear they experience is annoyance, as if they’ve been reminded of a particularly stubborn splinter that might never be removed. Guest curator Sujong Song presents with Five Views from Korea five projects from photographers, which are the result of these frustrations felt in everyday life by this reality.

‘Ultimately, these are narratives regarding five perspectives on either the nations tied to the divided Korean Peninsula or the identity of those who live within the countries’ influences. Invisible ideologies attempt to control us in whatever way possible, while we struggle to overcome that restraint. It is the things unseen that dig most deeply into our everyday lives, irrevocably bore into our skin.’

On this blog we’ve looked at some of the photographers included in the exhibit, and reviews of books that include work of at least one of the others are in the works. This looks like an interesting show. Too bad I won’t be able to get to Groningen to check it out. Hopefully there will be a catalog or accompanying book available.

Two Faces, Lee Duegyoung

Sometimes, the answers are all right in front of you. And at other times, small things obscure them.

An aside before the actual review: Lee Duegyoung’s Two Faces includes a list of notes by critic Lim Geun-jun that give detailed descriptions of his previous projects and working methods. Lim’s very clear description of Lee’s “Teheranno” as panoramic composites made from photographs taken from a helicopter with a downward facing camera to mimic satellite imagery clarifies for me the images I mentioned last week as a stand out in the 2012 Seoul Photo Festival. I had not connected them in my mind to Two Faces because Lee’s name was transliterated differently in the SPF catalog. For my part, I have always transliterated names as they are transliterated in the publication and will continue to do so despite the obvious possibility for missed connections. On to the review.

Lee Duegyoung maintains an incredible consistency of good ideas coupled with masterful execution and high-quality book design. Given his past exhibits and publications, it is little wonder that Two Faces is such a strong book. I may be faulted for wearing my heart on my sleeve here, but so be it. I like this book. Two Faces is one of the most engaging Korean photo books I have acquired recently. Both the content and design are outstanding; as a bonus the texts are clearly written and available in both Korean and English.

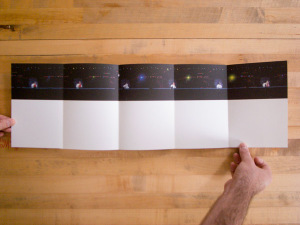

Two Faces comprises two panoramic photographs of the north and south banks of the Han River as it runs through Seoul. Lee composited roughly 13,000 photographs taken over four days from multiple river boats into two panoramic images. The two panoramas run essentially unbroken opposite from one another, top and bottom, across the accordion pages of the book. The book places the reader almost in the prow of a boat from which he can look left and right at the two banks of the Han. The “accordion” is perfect bound along one edge preventing the reader from opening it up to peruse long stretches of the panoramas.

Due to the inevitable perspective shifts caused by shooting from a moving platform, some tall buildings away from the river’s banks appear multiple times in slightly shifted positions. This gives an experiential edge to the photographs. Just as an actual viewer on a river cruise might espy the same edifice from multiple angles over the course of the journey, so too is the reader treated to this experience. Any sense of an absolute recording of the river is broken, the panoramas present a view that is spatial and temporal and hint at a continuum of possible views.

Lim notes that one of Lee’s influences is Ed Ruscha’s trilogy of artists books: Every Building on the Sunset Strip, Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations and Thirty-Four Parking Lots. This makes perfect sense to me, though the incredible breadth of Lee’s effort brings to my mind another project: Eugene Smith’s Pittsburgh. in Two Faces Lee has taken an equally ambitious target but rather than get bogged down in endless possibility has brought the work to a magnificent completion through a tightly focused conceptual framework and equally tight physical form. I’m sure there’s a jazz metaphor here, but I’m not a jazz guy.

The physical form effectively contributes to the conclusion of Lee’s Hangang trilogy by referencing the previous projects. The cover presents us with a complete foreshadowing of the work within: the panoramas have been compressed into the length of the wraparound cover. This calls to mind the time compressed video that accompanied the exhibition of Lee’s Hangang Project II – 25 Bridges. Lim notes the video, and I take take his note a step further to explicitly make the connection with Two Faces‘s cover. So too would I point out the somewhat obvious connection of the book’s accordion form to his 69 Snack Booths catalog which also employed an accordion form. These small formal and technical echoes that tie project to project create a sense of structured completeness.

I’ll end with a small personal detail that I enjoy: in the panorama that tracks the north bank of the Han, Lee has photographed my mother-in-law’s apartment building under construction shortly before she would have moved in.

Singular concept.

Tight design.

A work fully thought through.

Two Faces

Lee Duegyoung

Written by: Lim Guen-jun and Rhee Z-Won

Translated by: Choi S. Min and Kim Sung

Edited and Designed by: Suki and Min

Specter Press, Seoul

Edition of 700

2010

Like a Program; Kim Sang-Gil

Good photography. Dark, rough printing. Off white paper. Small design flourishes. Wonderful object-ness.

Given my predilections I ought to like this book. I don’t.

My impression is that more and more photo books being made in Korea lately are exquisite objects that mirror and enhance the photography contained within. (Next week’s review will be of one of these.) In the past, I found that many photo books in Korea were simply exhibition catalogs (often beautifully made but still catalogs). Like a Program on a cursory examination appears to be a wonderful object, and it is, but this object-ness is out of whack to the photography within and overwhelmed by the all you can eat buffet of an exhibition catalog that it truly is.

It may be unfair to judge an exhibition catalog for failing as a photo book. Oh well.

Kim Sang-Gil’s photographs limn a porous boundary between artifice and sincerity. Like a Program contains three of Kim’s projects that approach this boundary from different directions and a fourth that is about something (else). The moments in “Motion Picture” appear to be caught from life, but their captions reveal them to be staged. The subjects are models and actors between or in the midst of takes. “Off-line” depicts communities that have come together around shared interests. These interests can be as simple or shallow as brand affiliation and yet the group identity or sense of community is no less sincere than in any other group or community. “Re-model” is photographs of empty commercial interior spaces either waiting to be used or in the process of being made ready for use but that lack the qualities that actually being used will embue them with. An empty space might be intended as an office, but until it is used it is little different than an unused mall interior. The final series in the book is “Display.” This is comprised of details of building design features: a handicap lift rail; an elevator door; a revolving door; a parking elevator system. I do not know how these four photographs relate to the previous three series.

The work in the book, while having a loosely unifying theme, is too broad. Moving from one project to the next is jarring.

The choice to print all of the work in the book in low contrast black and white is odd given that Kim Sang-Gil works in color. The printing is actually quite beautiful in its way, but it is wrong for almost all of the work.

“Off-line_burberry internet community” offers the opportunity for a direct comparison between Like a Program’s grayscale printing and a color presentation. The image appears in glorious glossy color on the cover (and in the interior) of the 2009 exhibition catalog Chaotic Harmony (Museum of Fine Arts Houston and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2009).The flat gray tones in Like a Program dull the image, make it boring.

The images from “Motion Picture” are similarly dulled to death by the monotone printing. These images have subtle color and a cinematic presence–which makes sense given how they were made. Looking at these photographs I am reminded of Philip-Lorca Dicorcia’s Hustlers with their seemingly natural light that bathes everything in the frame with a kind of heightened sense of being real. This heightened sense of the real is at the heart of what “Motion Picture” is about. It is a physical trace of Kim’s capital “I” Idea. Why strip that from the photographs?

This is not a knock on the photography or the photographer (though the buck has to stop somewhere). Motion Picture_inquiry and Motion Picture_the message and Motion Picture_hand clapping are all weirdly wonderful. Off-line_burberry internet community, Off-line b&w sneakers internet community and Off-line_the sound of music internet community are likewise beautifully bizarre. I imagine that large prints from Re-Model would have an amazing presence on the wall. This is good work.

This is a knock on the book: There was obvious care made in the design and printing and yet somehow the design choices are mismatched to the content. The design and printing are good (in and of themselves at least); the photography is good; the combination is not good.

If one has nothing nice to say, we are often told, say nothing at all. Ah… Well. I don’t think my writing this criticism of a book published eight years ago will put any kind of dent in Kim’s reputation. I’m just some dude and he’s an internationally known artist. I have no ax to grind here; I like Kim’s photographs and bought the book because I wanted to like it. It is disappointing that Like a Program occupies the no man’s land that it does: it has lovely object qualities and yet is primarily an exhibition catalog.

Like a Program

Kim Sang-Gil

Project Space Sarubia, Seoul

2005

SSE Project and SSE Zine; Young Pil Yoo

A package arrived from Korea yesterday. New SSE Zines! And stickers and postcards to boot.

SSE Project is an online gallery; each exhibit is also printed as SSE Zine. Given that SSE-P and SSE Zine are a single project in their own right I’m writing this review of the whole venture. While I certainly might have my favorite issues, it is the overarching consistency of SSE-P that I am enamored of. This review, then, is of Young Pil Yoo’s efforts to “offer a wide perspective to the public and help communication between artist and audience.”

In the New York Times a couple of days ago, Holland Cotter had a piece describing “a collection of complaints and a few (very few) ideas for change” that he has regarding the arts in New York City. In his view, big money (the art industry) has again come to the fore in the art world (though one could certainly argue that it is always at the fore) and is distorting the art world in terms of “what kind of art is made, and how art is presented in the media and in museums.” He closes his article with this:

But when the rents get too high, or the economy fails, or art buying falls out of fashion, and the art industry decides to liquidate its overvalued assets and leave? Artists, the first and last stakeholders, will have themselves to fall back on. They’ll learn to organize and agitate for what they need, to let City Hall know, in no uncertain terms, that they’re there. They’ll learn to share, not just on special occasions, but all the time. They’ll learn that art and politics are inseparable, and both can be anything and everything. They’ll learn to bring art back from the brink of inconsequence.

As someone long on questions and short on answers, let me ask: Why not start now?

YP (as Young Pil presents himself in SSE-P and his social media channels) started SSE Project six years ago. He understood Cotter’s concerns (though without the New York City specifics) in 2008 and has created a platform through which young artists can share their work. SSE-P strikes a fine balance between the new world flattening of distribution opportunities presented by the web and old school print media that exists as objects in the real world. YP is putting artists into the world. He is helping them to share all of the time.

SSE-P is a distant less commercial cousin of Jen Bekman’s 20×200. While Bekman’s endeavor aims to make art accessible by way of affordability, YP is looking to make art simply accessible. The website presents each exhibit in full. Social media channels trumpet the exhibits in conjunction with real world launch parties. Artists are linked to directly from the SSE-P site. The only thing SSE-P sells is the zine (and SSE-P stickers and postcards…), and these are priced so cheaply that I suspect they simply cover the cost of printing the next zine. (In Seoul bookstores the zines are generally priced between $6 and $10; online ordering with international shipping is slightly pricier.)

Without a clear metric, it is hard to evaluate how successfully SSE-P is fulfilling its mission–and that isn’t my job, really. However, so as not to be one of those critics writing only to “broadcast names and contribute to fame,” I’ll make a go of it anyway.

“Wide perspective” seems like a good place to start. The latest issue is #48; I have 12 issues on hand. I’ve acquired issues dealing primarily with photography, though of those on hand two are painting and another illustration. The remaining 36, many of which I’ve seen in person and others which I’ve seen only online, are a mixture of painting, drawing, illustration and multimedia. The artists are mostly Korean, though a number of western artists have also worked with SSE-P. The aesthetic range of the presented work is, well, wide: black and white grit from Novo and Yourim Kim documenting tattoo culture; young women in the flush of life from Yina Kim; rough aggressive political paintings from VS; “simple and still” subtle color from Ye Rin Mok. Nam Ji Yeon’s paintings are fucking weird–I’m clearly missing something. Hasisi Park shows and conceals.Son Dong Joo photographs a love letter. SSE-P hits the wide mark.

It is harder to evaluate how well the projects is helping communication between audience and artists. YP has a following of nearly 800 on Twitter. The last opening drew nearly 100 yes RSVPs through Facebook and pictures show a well attended opening. Beyond that weak evidence, I can only guess based on anecdotal evidence: my experience is that the zines are everywhere, though often hard to find: many sell out quickly. My evaluation? Forget the numbers; it is the intent that is most important. YP is trying, and I would say (am saying) that trying is succeeding in this endeavor.

Once again, to no one’s surprise, I’m taken by a small publisher ( / online gallery). YP designs each (or at least most) of the zines himself. The zines are roughly 28 pages, well printed on matte paper, saddle stitched, either 5 3/4″ x 8 1/4″ or 5″ x 7 1/4″ and in an edition of either 500 or 1000. The design is understated, generally, so that the art is front and center. A couple include an accompanying poster.

Lest anyone think I’m gushing here, I’ll note that I skipped the two volumes of Boys on Film and Girls on Film. These publications didn’t do it for me. For completeness’ sake I ought to have simply purchased them through gritted teeth; but, they’re just empty photo calories, and I passed.

If you’re in Seoul, swing by The Book Society, Your Mind or the design shop on the ground floor of the Sangsang Madang building in Hongdae and check out a couple of the zines. Elsewhere in Korea, check in at your nearest hip art shop; you’ll probably find SSE Projects publications. If you’re not in Korea, check out the SSE-P site, follow Young Pil on Twitter (@yp_art) or have a couple of zines shipped to your door. SSE Projects is hot. I’m hooked. You will be too.

2011, 5, 24, Tuesday; Jo Hyo Joon

This book clearly illustrates the precipice along which this blog walks: sitting at the intersection of photographs and text, and as the text is only in Korean, it is beyond my full understanding. This is a flaw of this blog that I am all too aware of. Over-arching ideas, the photographs and physical books I understand. Korean Text and the nuance it might bring often eludes me. I note this because this is a book that I quite enjoy even with my understanding hobbled by my inability to fully appreciate the text. I don’t see this as a fatal flow but certainly one of which I am aware.

2011, 5, 24, Tuesday mines multiple perspectives of a single day. Each of the subjects in the book was in the same place, at the same time and doing the same task. The book is comprised of their individual accounts describing what happened that day; each account is accompanied by a portrait. Though I cannot read the text and despite the fact that the tasks were done for the military, the events described appear to be banal. It is (I assume) the small differences between their accounts that are meaningful.

Each text is accompanied by a portrait of the man who wrote it. The portraits are all snapshots: loose, familiar, affectionate but without affectation. I assume the photographs were made by Jo who designed the book and that they were shot with a point and shoot with a built in flash. They would be better considered alongside Nikki S. Lee’s “snapshots” rather than Terry Richardson’s. When a journal entry runs longer than a page, a photograph of the location sits across from the additional page of text. The opening and closing photographs are all of the location.

Published by Corners, it is no surprise that the printing is rough risograph. The photographs are all in a limited blue tonality. The clipped tones nonetheless convey much and suggest more. The next to last photograph in the book, one of the few that isn’t a portrait, is a broad sky above distant layered hills with a flash-lit fence in the foreground. The regularity of the fence–harshly lit by the flash, sets off the subtlety of the rows of hills and the glow of low clouds below a clear sky above. Where the blue ink blocks up in the dark tones of the hills there is wonderful play between the ink and the paper’s fibers. One can almost see trees, branches and pine needles.

As might be gleaned from the types of books that I have written about (and purchased before doing so) I like small books that delve into small ideas and I like quirky presses that make the most of their limits. Corners is just such a press, and this is just such a book.

2011, 24, 5, Tuesday

Jo Hyo Joon

Corners

2012, 3, 1