A package arrived from Korea yesterday. New SSE Zines! And stickers and postcards to boot.

SSE Project is an online gallery; each exhibit is also printed as SSE Zine. Given that SSE-P and SSE Zine are a single project in their own right I’m writing this review of the whole venture. While I certainly might have my favorite issues, it is the overarching consistency of SSE-P that I am enamored of. This review, then, is of Young Pil Yoo’s efforts to “offer a wide perspective to the public and help communication between artist and audience.”

In the New York Times a couple of days ago, Holland Cotter had a piece describing “a collection of complaints and a few (very few) ideas for change” that he has regarding the arts in New York City. In his view, big money (the art industry) has again come to the fore in the art world (though one could certainly argue that it is always at the fore) and is distorting the art world in terms of “what kind of art is made, and how art is presented in the media and in museums.” He closes his article with this:

But when the rents get too high, or the economy fails, or art buying falls out of fashion, and the art industry decides to liquidate its overvalued assets and leave? Artists, the first and last stakeholders, will have themselves to fall back on. They’ll learn to organize and agitate for what they need, to let City Hall know, in no uncertain terms, that they’re there. They’ll learn to share, not just on special occasions, but all the time. They’ll learn that art and politics are inseparable, and both can be anything and everything. They’ll learn to bring art back from the brink of inconsequence.

As someone long on questions and short on answers, let me ask: Why not start now?

YP (as Young Pil presents himself in SSE-P and his social media channels) started SSE Project six years ago. He understood Cotter’s concerns (though without the New York City specifics) in 2008 and has created a platform through which young artists can share their work. SSE-P strikes a fine balance between the new world flattening of distribution opportunities presented by the web and old school print media that exists as objects in the real world. YP is putting artists into the world. He is helping them to share all of the time.

SSE-P is a distant less commercial cousin of Jen Bekman’s 20×200. While Bekman’s endeavor aims to make art accessible by way of affordability, YP is looking to make art simply accessible. The website presents each exhibit in full. Social media channels trumpet the exhibits in conjunction with real world launch parties. Artists are linked to directly from the SSE-P site. The only thing SSE-P sells is the zine (and SSE-P stickers and postcards…), and these are priced so cheaply that I suspect they simply cover the cost of printing the next zine. (In Seoul bookstores the zines are generally priced between $6 and $10; online ordering with international shipping is slightly pricier.)

Without a clear metric, it is hard to evaluate how successfully SSE-P is fulfilling its mission–and that isn’t my job, really. However, so as not to be one of those critics writing only to “broadcast names and contribute to fame,” I’ll make a go of it anyway.

“Wide perspective” seems like a good place to start. The latest issue is #48; I have 12 issues on hand. I’ve acquired issues dealing primarily with photography, though of those on hand two are painting and another illustration. The remaining 36, many of which I’ve seen in person and others which I’ve seen only online, are a mixture of painting, drawing, illustration and multimedia. The artists are mostly Korean, though a number of western artists have also worked with SSE-P. The aesthetic range of the presented work is, well, wide: black and white grit from Novo and Yourim Kim documenting tattoo culture; young women in the flush of life from Yina Kim; rough aggressive political paintings from VS; “simple and still” subtle color from Ye Rin Mok. Nam Ji Yeon’s paintings are fucking weird–I’m clearly missing something. Hasisi Park shows and conceals.Son Dong Joo photographs a love letter. SSE-P hits the wide mark.

It is harder to evaluate how well the projects is helping communication between audience and artists. YP has a following of nearly 800 on Twitter. The last opening drew nearly 100 yes RSVPs through Facebook and pictures show a well attended opening. Beyond that weak evidence, I can only guess based on anecdotal evidence: my experience is that the zines are everywhere, though often hard to find: many sell out quickly. My evaluation? Forget the numbers; it is the intent that is most important. YP is trying, and I would say (am saying) that trying is succeeding in this endeavor.

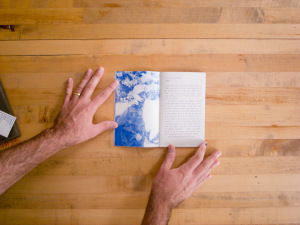

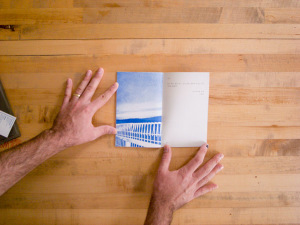

Once again, to no one’s surprise, I’m taken by a small publisher ( / online gallery). YP designs each (or at least most) of the zines himself. The zines are roughly 28 pages, well printed on matte paper, saddle stitched, either 5 3/4″ x 8 1/4″ or 5″ x 7 1/4″ and in an edition of either 500 or 1000. The design is understated, generally, so that the art is front and center. A couple include an accompanying poster.

Lest anyone think I’m gushing here, I’ll note that I skipped the two volumes of Boys on Film and Girls on Film. These publications didn’t do it for me. For completeness’ sake I ought to have simply purchased them through gritted teeth; but, they’re just empty photo calories, and I passed.

If you’re in Seoul, swing by The Book Society, Your Mind or the design shop on the ground floor of the Sangsang Madang building in Hongdae and check out a couple of the zines. Elsewhere in Korea, check in at your nearest hip art shop; you’ll probably find SSE Projects publications. If you’re not in Korea, check out the SSE-P site, follow Young Pil on Twitter (@yp_art) or have a couple of zines shipped to your door. SSE Projects is hot. I’m hooked. You will be too.