Good photography. Dark, rough printing. Off white paper. Small design flourishes. Wonderful object-ness.

Given my predilections I ought to like this book. I don’t.

My impression is that more and more photo books being made in Korea lately are exquisite objects that mirror and enhance the photography contained within. (Next week’s review will be of one of these.) In the past, I found that many photo books in Korea were simply exhibition catalogs (often beautifully made but still catalogs). Like a Program on a cursory examination appears to be a wonderful object, and it is, but this object-ness is out of whack to the photography within and overwhelmed by the all you can eat buffet of an exhibition catalog that it truly is.

It may be unfair to judge an exhibition catalog for failing as a photo book. Oh well.

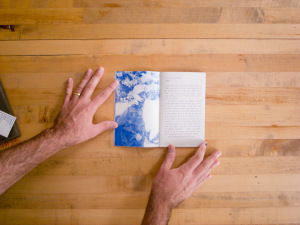

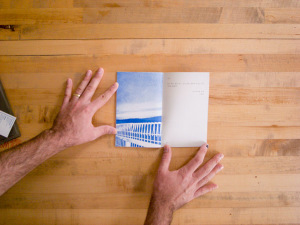

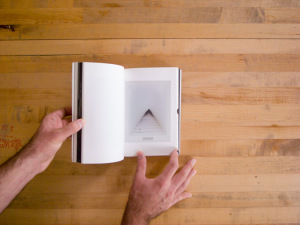

Kim Sang-Gil’s photographs limn a porous boundary between artifice and sincerity. Like a Program contains three of Kim’s projects that approach this boundary from different directions and a fourth that is about something (else). The moments in “Motion Picture” appear to be caught from life, but their captions reveal them to be staged. The subjects are models and actors between or in the midst of takes. “Off-line” depicts communities that have come together around shared interests. These interests can be as simple or shallow as brand affiliation and yet the group identity or sense of community is no less sincere than in any other group or community. “Re-model” is photographs of empty commercial interior spaces either waiting to be used or in the process of being made ready for use but that lack the qualities that actually being used will embue them with. An empty space might be intended as an office, but until it is used it is little different than an unused mall interior. The final series in the book is “Display.” This is comprised of details of building design features: a handicap lift rail; an elevator door; a revolving door; a parking elevator system. I do not know how these four photographs relate to the previous three series.

The work in the book, while having a loosely unifying theme, is too broad. Moving from one project to the next is jarring.

The choice to print all of the work in the book in low contrast black and white is odd given that Kim Sang-Gil works in color. The printing is actually quite beautiful in its way, but it is wrong for almost all of the work.

“Off-line_burberry internet community” offers the opportunity for a direct comparison between Like a Program’s grayscale printing and a color presentation. The image appears in glorious glossy color on the cover (and in the interior) of the 2009 exhibition catalog Chaotic Harmony (Museum of Fine Arts Houston and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2009).The flat gray tones in Like a Program dull the image, make it boring.

The images from “Motion Picture” are similarly dulled to death by the monotone printing. These images have subtle color and a cinematic presence–which makes sense given how they were made. Looking at these photographs I am reminded of Philip-Lorca Dicorcia’s Hustlers with their seemingly natural light that bathes everything in the frame with a kind of heightened sense of being real. This heightened sense of the real is at the heart of what “Motion Picture” is about. It is a physical trace of Kim’s capital “I” Idea. Why strip that from the photographs?

This is not a knock on the photography or the photographer (though the buck has to stop somewhere). Motion Picture_inquiry and Motion Picture_the message and Motion Picture_hand clapping are all weirdly wonderful. Off-line_burberry internet community, Off-line b&w sneakers internet community and Off-line_the sound of music internet community are likewise beautifully bizarre. I imagine that large prints from Re-Model would have an amazing presence on the wall. This is good work.

This is a knock on the book: There was obvious care made in the design and printing and yet somehow the design choices are mismatched to the content. The design and printing are good (in and of themselves at least); the photography is good; the combination is not good.

If one has nothing nice to say, we are often told, say nothing at all. Ah… Well. I don’t think my writing this criticism of a book published eight years ago will put any kind of dent in Kim’s reputation. I’m just some dude and he’s an internationally known artist. I have no ax to grind here; I like Kim’s photographs and bought the book because I wanted to like it. It is disappointing that Like a Program occupies the no man’s land that it does: it has lovely object qualities and yet is primarily an exhibition catalog.

Like a Program

Kim Sang-Gil

Project Space Sarubia, Seoul

2005