This isn’t a review of a single book but rather a first look at a publishing initiative. Noonbit has embarked on an ambitious project of releasing a broad series of affordably priced books that expand the audience for photo-books in Korea: Noonbit Collection of Korean Photographer’s Works. The intent is for these books to be accessible, approachable and readable in the same way that novels or books of poetry are. These are nice but not lavishly produced softcover volumes with straight forward design. In late 2014 they released the first set of ten books. These ten will be followed with additional sets of ten books.

The first series of ten books is:

- 01 DMZ, Koo Bohnchang

- 02 The Southern Line of East Coast, Kim Geum-Soon

- 03 On the Road, Kim Moon-Ho

- 04 The Reason of Affection for a Walk / Zoology, Kim Bien-hun

- 05 Daily Reduced Special Rate, Kim Jeeyoun

- 06 Snow, Min Byun Hun

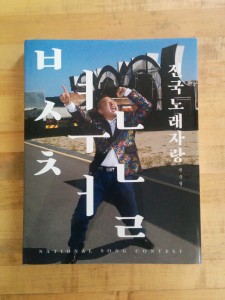

- 07 National Song Contest, Byun Soon-Cheol

- 08 Beach Kamami in YeongGwang, Shin Eun-Kyung

- 09 Pumgeolri in Soyangho (lake), Im Jay Cheon

- 10 Hands, Jun Min Cho

As may be apparent from the titles and photographers chosen, this series goes beyond simply making photography accessible: it plants a flag for a certain kind of photography: straight documentary. It also lays out an over-arching examination of “Korean-ness.” The following Wright Morris quote opens an unrelated book on landscape photography I’ve just begun reading: “The camera eye is the one in the middle of our forehead, combining how we see with what there is to be seen.” Here we have ten Korean photographers documenting different locations or subjects throughout Korea; the “how we see” extending across these books is the publisher’s vision. At a meta level, the totality of this series is (or will be) is Noonbit’s vision of Korean-ness and Korean photography. (It will be interesting to see the overlaps and divergences with the Korean photography overview project that Suejin Shin is working on.)

In a way, this series is a product of the digital age. It can be seen as a traditional media outlet’s response to websites and blogs like Lenscratch, Feature Shoot, burn or 500 Photographers. These sites present an even more affordable (free) and accessible (online, immediate) selection of photography that reaches across cultures, borders and styles. One might wonder why Noonbit didn’t make its initiative in digital space. Why not make this a long-running digital property like 500 Photographers except focused on Korean photographers? Why not make this a blog like Conscientious that presents critical context for the work?

Noonbit offers photographers the status conferred by the lasting nature of a physical book. A blog post may live forever in the cloud, but it is ultimately ephemeral, replaced endlessly by new content. A thousand (or a million!) people may see a blog post, but only as part of a flow of content. A book is an artifact in the physical world; its journey may touch only a few people but it will be a continuing fact for those people. Its physical state makes its impact longer lasting.

Both the digital and the physical have their value and their uses. I believe that an opportunity may have been missed in not making this series a marriage between the two. What rich opportunities for interaction could have been presented between the physical book and an expansive digital mirror? What kind of a community might have grown around the books? What conversations might have been sparked? How many more people might have been reached and touched by these works? The likelihood of the physical books making it to the West is slim, but a multi-lingual web platform or an app presented in conjunction with the physical books could have reached outside Korea creating a richly interactive environment to explore these photographers, their works and the contexts within which they exist.

As they are, the books are a wonderful introduction to Korean photography, or at least a subset of Korean photography. It would be wonderful if a retailer like Photo-Eye, Dashwood or the ICP’s bookshop saw fit to bring them to the US.

I’ll be writing about some of these books individually in greater detail at a later date.

(This post will be updated with images.)

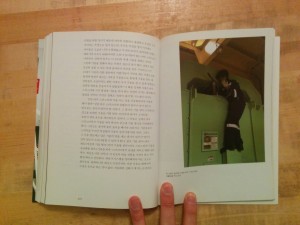

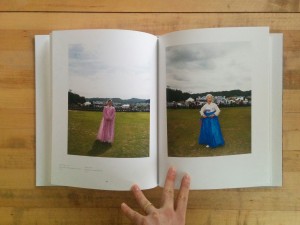

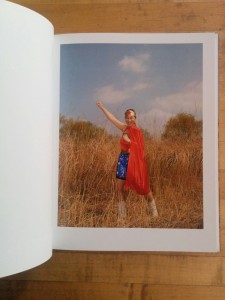

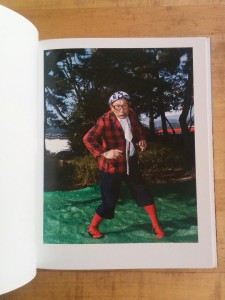

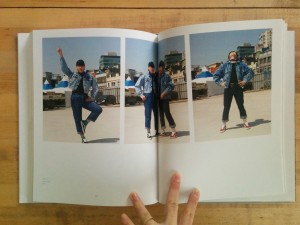

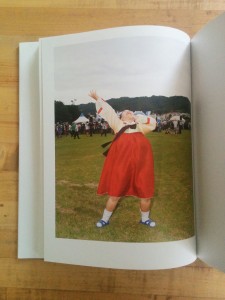

The nominal subject of National Song Contest is contestants of the television show of the same name. Running for over thirty years, the show’s premise is much like “America’s Got Talent,” if that show were combined with a comedic circus act. Choel’s subjects are full of ardor; each is a uniquely live wire. Choel does not hold them back. He seems rather to push them into hamming it up for the camera–pushing them in such a way that their acts become archetypes.

The nominal subject of National Song Contest is contestants of the television show of the same name. Running for over thirty years, the show’s premise is much like “America’s Got Talent,” if that show were combined with a comedic circus act. Choel’s subjects are full of ardor; each is a uniquely live wire. Choel does not hold them back. He seems rather to push them into hamming it up for the camera–pushing them in such a way that their acts become archetypes.

It is hard to reduce the project to a representative sample, so I’ll simply note one image that makes me smile. A

It is hard to reduce the project to a representative sample, so I’ll simply note one image that makes me smile. A  It would be naive to imagine that not one of these contestants harbors hope of fame or fortune through the contest, but it is entirely the joy of the performance that drives the photographs. If one were to shoot a similar project here in America, it would likely by tinged by an ironic sadness of the desperation for fame or the mocking overtones of the ‘loser edit.’ In contrast, Cheol’s lens affectionately finds antic joy.

It would be naive to imagine that not one of these contestants harbors hope of fame or fortune through the contest, but it is entirely the joy of the performance that drives the photographs. If one were to shoot a similar project here in America, it would likely by tinged by an ironic sadness of the desperation for fame or the mocking overtones of the ‘loser edit.’ In contrast, Cheol’s lens affectionately finds antic joy.  One might be tempted to label and dismiss Choel’s National Song Contest as camp, but this would be a mistake. The loose typographical framework, reminiscent of August Sanders’ expansive People of the 20th Century, becomes a cipher through which Choel is able to decode the breadth of “Korean-ness”. It is not only the contestants and their personas that transmit this information, but also the details of landscape and location that are the backdrop of the portraits. Likewise, it would be a mistake to forget that the photographs are a cacophony of crazy performances being conducted in enthusiastic ernest for the camera. The photographs are, quite simply, a lot of fun.

One might be tempted to label and dismiss Choel’s National Song Contest as camp, but this would be a mistake. The loose typographical framework, reminiscent of August Sanders’ expansive People of the 20th Century, becomes a cipher through which Choel is able to decode the breadth of “Korean-ness”. It is not only the contestants and their personas that transmit this information, but also the details of landscape and location that are the backdrop of the portraits. Likewise, it would be a mistake to forget that the photographs are a cacophony of crazy performances being conducted in enthusiastic ernest for the camera. The photographs are, quite simply, a lot of fun.  Yoon Seungjun’s Automatic Description is a book of car photographs. These photographs are not your everyday glossy advertisement for this years latest iteration of automotive desire. There is no glitz, no sparkle, no sex appeal. These cars are dead.

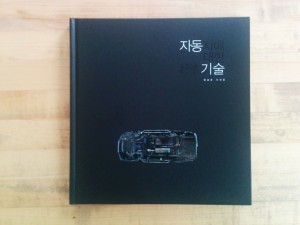

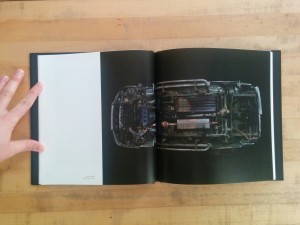

Yoon Seungjun’s Automatic Description is a book of car photographs. These photographs are not your everyday glossy advertisement for this years latest iteration of automotive desire. There is no glitz, no sparkle, no sex appeal. These cars are dead.  Automatic Description is broken into chapters that build one upon the other. The book begins with “Anatomical Chart – appropriation,” a typological series of images of individual car’s under carriages shot against a black ground. These photographs reduce the automobile to its basic structural form, minus wheels. We see the body frame with the suspension structures, transmission, driveshaft, and exhaust systems hanging from it. With their wheels removed and reoriented in space, these automobiles are no longer vehicles but rather abstract forms. Looking closely, one can find narratives in the abstraction: oil leaks, broken drive shafts, scrapes, rust and burn (?) marks. There are stories in these forms however banal they might be.

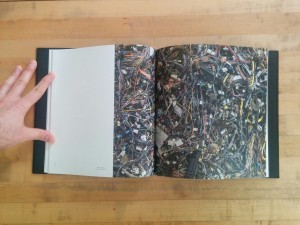

Automatic Description is broken into chapters that build one upon the other. The book begins with “Anatomical Chart – appropriation,” a typological series of images of individual car’s under carriages shot against a black ground. These photographs reduce the automobile to its basic structural form, minus wheels. We see the body frame with the suspension structures, transmission, driveshaft, and exhaust systems hanging from it. With their wheels removed and reoriented in space, these automobiles are no longer vehicles but rather abstract forms. Looking closely, one can find narratives in the abstraction: oil leaks, broken drive shafts, scrapes, rust and burn (?) marks. There are stories in these forms however banal they might be. Chapter two, “Anatomical Chart – combination,” moves from individual vehicles to the aggregation of them. Vehicles are no longer individual stories. Instead, they interlock in stacks and heaps. Crumpled cars are crumpled in a pile. Hundreds of gas tanks are mounded together. Wiring harnesses are enmeshed in a chaotic singular mess. Pipes of every description writhe together like so many snakes in a pit. The singular story has given way to a history of multitudes. Yoon brings his camera in close for these photographs. We see no ground; the subject fills the frame. We are again seeing this automotive wreckage as abstraction.

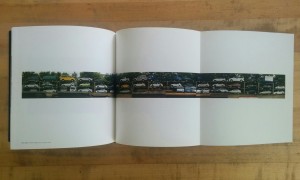

Chapter two, “Anatomical Chart – combination,” moves from individual vehicles to the aggregation of them. Vehicles are no longer individual stories. Instead, they interlock in stacks and heaps. Crumpled cars are crumpled in a pile. Hundreds of gas tanks are mounded together. Wiring harnesses are enmeshed in a chaotic singular mess. Pipes of every description writhe together like so many snakes in a pit. The singular story has given way to a history of multitudes. Yoon brings his camera in close for these photographs. We see no ground; the subject fills the frame. We are again seeing this automotive wreckage as abstraction.  “Scraped Car Chart – parade” is the third chapter and takes us off into the new territory of documentary context. Yoon has pulled back to show us the space in which these cars are resting. We see the rows of racks and risers on which the cars rest. Some of the vehicles are half dismantled; others seem as shiny as new. Sunlight glints off of chrome and polish, still. In the middle of the chapter a gatefold presents a long panoramic image of column after column of junked cars. There are obvious joints in the image; it is not a singular panorama. Yoon has constructed this image–no different than we have constructed this entire infrastructure of disposal (such as it is). Just as the infrastructure of roads, highways and city streets has been built to accommodate the relentless drive of automobile culture so has an infrastructure been built to support the end stage inherent in consumerism. When millions are buying cars, millions are inevitable discarding them as well.

“Scraped Car Chart – parade” is the third chapter and takes us off into the new territory of documentary context. Yoon has pulled back to show us the space in which these cars are resting. We see the rows of racks and risers on which the cars rest. Some of the vehicles are half dismantled; others seem as shiny as new. Sunlight glints off of chrome and polish, still. In the middle of the chapter a gatefold presents a long panoramic image of column after column of junked cars. There are obvious joints in the image; it is not a singular panorama. Yoon has constructed this image–no different than we have constructed this entire infrastructure of disposal (such as it is). Just as the infrastructure of roads, highways and city streets has been built to accommodate the relentless drive of automobile culture so has an infrastructure been built to support the end stage inherent in consumerism. When millions are buying cars, millions are inevitable discarding them as well.