This book is an escape, and I need one. I am in Kings County Superior Court serving on Jury Duty. Thus far, I am doing little more than sitting and waiting. Having brought Oh SeBeom’s 31 Days 807.3km was a good decision as it provides welcome distraction.

31 days 807.3km is a small volume, roughly the size of a Moleskin notebook, chronicling a 31 day 801.3km trip across northern Spain. This book is one part of a larger project that includes web and video components as well. The project as a whole is one part again of Oh’s overarching one man project: World of DDanjit I cannot read any of the site’s text, but it seems to be a cataloging of the world, something to which I can relate.

31 days 807.3km is broken into roughly three equal sections. The first is a reproduction of Oh’s Moleskin journal pages written during the trip. It is from these journals that the book takes its size and shape, imitating a Moleskin notebook. This section has feeling. The handwriting has smudged and we can see text bleeding through from the backside of each page. As we read one experience we anticipate what is to come and reflect on what happened previously. This text is, obviously enough, in Korean with bits of copied text and web URLs in English. As I cannot read this text, I will say only that the reproduction of the notebook pages feels right; I feel like I’m being stealing into someone’s private thoughts (that were left laying about so I might buy them…). I assume that if I could read the text, this is what I would find, the starts and stops of experience.

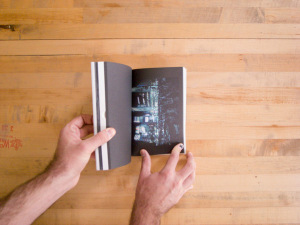

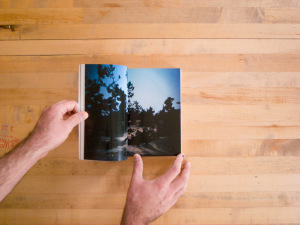

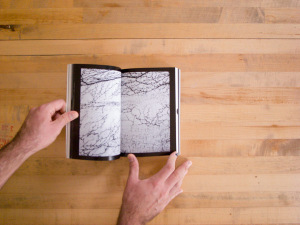

The second section is a series of photographs that reprise the travelogue in visual form. The bulk of the photographs are landscapes; many are the well worn trope of a road or track receding towards the horizon. There are few people or buildings. The photographs are like walking: one foot in front of the other, slowly building into a journey of 807.3 kilometers. Several photographs do stand above and are absolutely beautiful in their atmospheric quality. One, in particular, grabs my attention: in the foreground there are mounds of dirt that look like Korean tombs but are nothing more than piles of fill, in the middle ground a line of trees extends halfway across horizon with the last few trees wind blown back, and in the background half screened by the trees a small town gives way to a blue horizon beneath a blue sky. The photographs are all horizontal, printed full page, two to a spread so that one must turn the book sideways to see them properly. There are two exceptions to this: a vertical of a church is run halfway (and could have been edited out) and the closing horizontal image of the sea that is run double truck also and forces the reader to turn the book back to its normal orientation. It is a nice transition.

The third section we return to text. Days, dates, locations and distances are in large blue lettering overlaid on top of background text describing the journey. Facts and figures; cold and hard. The design amplifies the content. We end with a blue map dotted with (Google) map pins.

We have three travelogues that reinterpret the same trip through different filters. We begin with the personal experience: direct, smudged, imperfect, tangential. One event or thought bleeding between past and future experiences. Our journey is next mediated by a machine eye. We have facts and visual clues but truth is still elusive. These facts are up for interpretation and reinterpretation. The suggest but cannot define. We end with a journey distilled into fact: distances traveled, cities visited, dates, times.

The journal pages I cannot understand, but I understand the idea of a journey that they embody. When I travel, I keep similar notebooks. The photographs present less a specific place for me than a rich suggestive vein of possibility. The facts and figures leave me cold and I can do little but flip through. It is the hand written notes and photographs that hold my attention. Neither provides me literal facts but each presents a journey taken and suggests journeys yet to be taken.

It all makes sitting in this windowless, fluorescent lit, cavernous room more bearable.

31 days 807.3km

Oh SeBeom

world-of-ddanjit.tistory.com/

*

*