Half a lifetime ago at NYU, I took a film class on post-colonialism. I remember few specifics of the course other than watching The Battle of Algiers and reading Franz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth. What has stuck with me was the idea that societal systems create tiers of privilege. Reading theories of the way oppression works and seeing this play out in real life through film made privilege, and it’s cousin bias, very real to me. To this day I am aware of my own biases and the privileges that I enjoy–as well as the discomfort that they can elicit.

Hein-Kuhn Oh’s Cosmetic Girls elicits just such a discomfort related to bias and privilege. I’d seen the book on the shelves of bookstores for a couple of years before I could bring myself to purchase it. It seemed like a book I ought to have on my shelves, but I feel dirty looking through it. The photographs don’t sexualize the girls in them but certainly do objectify those girls. The photographs make these girls into something to be looked at–and the photographer has done so meticulously and mercilessly. The photographs are unflinching. No detail goes unnoticed. (And it is entirely proper to refer to the subjects as girls; none are older than 23, most much younger.) There is an apparent male gaze.

Let it be said, though, that this is not the male gaze of Miroslav Tischy or Terry Richardson. It would be a mistake to lump Oh in with these two. Oh’s interest is anthropological inquiry–he is primarily fascinated by the value Korean society places on girls and young women. His intentions are more to do with representation than with the girls themselves. Read that again; it is the minor chords that run through his work that are discomfiting rather than an explicit raunchiness or misogyny.

His earlier Ajumma project (past review here) was a humorous but nonetheless direct and unflinching examination of middle aged Korean women. One might read the photographs as simply a look at “ajumma style” if not for the the central hot spot lighting that focuses attention on the women’s faces and the confrontational gaze of the women makes these works far more about the women than any overarching concern with style.

Consider the street style books Fruits by Shoichi Aoki or Scott Schumann’s The Sartorialist: in these books the photographs are about fashion on the streets. The subjects are generally smiling or upbeat; they seem to be enjoying being photographed. The photographs themselves are nearly style-less; there is no obvious hand of the photographer at work. Both photographers seem genuinely enthusiastic and excited by their subjects. The photographs are endearing and fun if somewhat vacuous.

In contrast, Oh’s photographs are brutal. He controls absolutely the environment in which the photographs are made. He controls the space. He controls the background. He controls the lighting. He controls the framing. The subjects are found on the street and invited to the studio to be photographed (an assistant not Oh himself makes these invitations). The subjects may have come to the studio willingly, but they look at the camera uneasily. None of the girls wear shoes (except in three photographs made outside of the studio). In some photographs the photographer has closed in on small details or just the girl’s legs. There is a kind of implicit misogyny.

Oh himself says that the kind of typological method that he has employed is “highly unethical” and a “cruel field”. He has chosen this means of representation because his subjects have chosen entertainers as their role models. He in turn makes his choices in regards to “a certain lighting, viewing angle and convention of photographic representation.” Nevermind that the convention he has chosen bears little resemblance to the highly stylized and idealized convention of photographic representation employed with celebrities.

Never mind that nowhere in Cosmetic Girls do we see the “numerous middle aged male fans known as samchon (Korean for ‘uncle’) and obba (Korean for ‘older brother’) [who] are enchanted by a variety of sexy girl groups that have gained popularity….” Instead it is the “sensitive girls” who “learn girliness from [these girl groups]” who are spread through the pages of Cosmetic Girls. Oh concludes his statement with this line: “The girls we can recognize are merely their facade and images.”

The photographs indeed depict a facade, but it is not that of the girls. These girls may wear make up, they may have had petit surgeries, and they may be conspicuously conscious of their appearances, but the facade here is not theirs. Whatever ten dollar words Oh wants to trot out talking about the photographs, it is in his use of typological processes and his stylistic decisions that he has constructed the most apparent facade: that of his own male gaze. In young women’s choice of entertainers as role models he sees a crevice in the societal facade and is picking at that crevice. As we peer through the crevice he has worried open, however, what we see is a male artist staring back.

Cosmetic Girls

Hein-Kuhn Oh

Edited by Jeong-eun Kim

Editorial Assistants Mi-rae Song, Vo-ram Lee

Designed by studio Dwyane Wade

Translation Jee-sun Park, Young Kang, Meeky Song, Cecilia J. Park

Printed and bound in Korea by Munsung

Digital Image Calibration Tae-yoon Kim, Kyung-sub Shin, Jae-woo Choi, Sang-kyun Ahn, Won-jung Jun, Hyo-joong Yoon, Hein-kuhn Oh

Published by IANNBOOKS

Published on the occasion of the exhibition Hein-kuhn Oh, <Cosmetic Girls>, Kukje Gallery

Catalogue planning by Kukje Gallery

© 2010

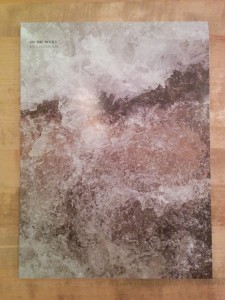

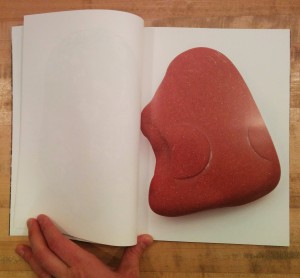

Let’s start with the conclusion: Kyoungtae Kim’s On the Rocks is an amusing, clever and honest book but not a grand one. That conclusion can be drawn from its subject matter: close-up macro photographs of small, everyday stones–roughly 2cm to 10cm in length. The bulk of the book is single pages in which each stone, floating in studio limbo, is enlarged to fill the page. Every singular stone is richly textured, wonderfully abstract and evocative–and yet humdrum.

Let’s start with the conclusion: Kyoungtae Kim’s On the Rocks is an amusing, clever and honest book but not a grand one. That conclusion can be drawn from its subject matter: close-up macro photographs of small, everyday stones–roughly 2cm to 10cm in length. The bulk of the book is single pages in which each stone, floating in studio limbo, is enlarged to fill the page. Every singular stone is richly textured, wonderfully abstract and evocative–and yet humdrum. Those three facts make me think the book came out of two questions: 1. When I travel to Europe, what can I bring back with me? 2. Now that I’ve got all these stones and pebbles sitting around, what can I do with them?

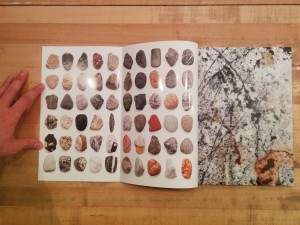

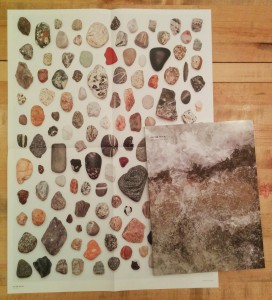

Those three facts make me think the book came out of two questions: 1. When I travel to Europe, what can I bring back with me? 2. Now that I’ve got all these stones and pebbles sitting around, what can I do with them? The photographs are also placed in grids in which the stones are seen relative to one another. On the inside covers, the stones are scaled to a single uniform size and printed in grids. In a nice touch, one must open the inside flap of the cover (onto which the full bleed cover image does not extend) to reveal the grids. A similar gridded spread follows the colophon page; on this grid the stones are scaled relative to one another and there is a scale so that one can determine how large each stone is in reality. This grid is repeated on a pull out poster on which the stones are printed life size (at 1:1 scale).

The photographs are also placed in grids in which the stones are seen relative to one another. On the inside covers, the stones are scaled to a single uniform size and printed in grids. In a nice touch, one must open the inside flap of the cover (onto which the full bleed cover image does not extend) to reveal the grids. A similar gridded spread follows the colophon page; on this grid the stones are scaled relative to one another and there is a scale so that one can determine how large each stone is in reality. This grid is repeated on a pull out poster on which the stones are printed life size (at 1:1 scale).

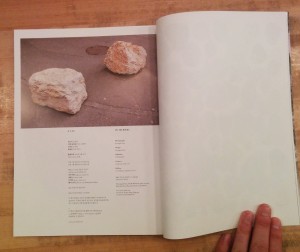

There is one outlier image. At the top of the colophon page is a photograph of two rocks sitting heavily on a paved street. These are

There is one outlier image. At the top of the colophon page is a photograph of two rocks sitting heavily on a paved street. These are