I’m out of town this week and part of next, so we’ll be on hiatus for this week and next. Reviews will return the second week of January.

Thanks for reading! A very Happy New Year to everyone.

I’m out of town this week and part of next, so we’ll be on hiatus for this week and next. Reviews will return the second week of January.

Thanks for reading! A very Happy New Year to everyone.

Kyusang Lee described Traces of Life: Seen Through Korean Eyes, 1945-1992 to me as being central to understanding Korean Photography. He felt so strongly about this that he literally chased after me following our interview to give me the book. Published in conjunction with a 2012 exhibit at The Korea Society in New York curated by Chang Jae Lee, the book outlines the post-World War II beginnings of a nascent autonomous Korean photographic tradition.

Photography first came to Korea through missionaries and other Western travelers and was later used by the Japanese as a tightly controlled political tool during the colonial period in Korea. Photographic representation of Korea and its people before 1945 was thus defined by an external perspective even when created by Koreans. In the politically charged environment of post-liberation Korea, the shift to self-representation by Korean photographers was dramatically felt and marked stylistically by an adoption of “life-realism”. This shift meant that “Koreans could finally see themselves from their own perspective,” according to Sun Il. Continue reading

On October 26th, Sangyon Joo of Datz Press came by KPB HQ to talk about her experiences as a publisher, curator and photographer. We’d first met during Printed Matter’s Art Book Fair at PS1 when I stopped by the Datz Press booth. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

On October 26th, Sangyon Joo of Datz Press came by KPB HQ to talk about her experiences as a publisher, curator and photographer. We’d first met during Printed Matter’s Art Book Fair at PS1 when I stopped by the Datz Press booth. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

MNM: Sangyon, thank you so much for making the time to come out to Brooklyn for this conversation. I am delighted to have you here and looking forward to the conversation.

SYJ: This is the fifth issue in our magazine, Gitz. Our conversation reminds me of somebody we profiled in the magazine, a Korean book collector who collects books about Korea. The books he collects were made by Western people who came to Korea in the early years, a hundred years ago. They saw the Korean people and culture and archived their observations in books. They collected and spread exotic cultures in their home countries. He goes to Western bookstores to collect these books about Korea and brings them back to Korea to show to us. It says a lot to me about how books work and how books can go around sharing culture. I think it is a very interesting job mixing Western views of Korea—we can see ourselves through their eyes and can find ourselves through their eyes. Something really great can be done with books.

Continue reading

As I’ve mentioned before this blog is a side project for me and a labor of love. Sometimes the day to day of being a working photographer gets in the way of writing reviews for this site. New content will be up soon, including a conversation with Sangyon Joo of Datz Press.

A related note: Datz Press is one of many publishers at the Unlimited Edition 7th Annual Seoul Art Book Fair happening right now. If you’re in Seoul check it out.

This review is being written to the clack of steel on steel as I ride Amtrak from Charlottesville, VA to New York City. My origin and destination stations today are practical rather than civic architecture. Train stations that proclaim civic greatness and interconnectedness such as Washington, DC’s Union Station or New York City’s former Pennsylvania Station (demolished in 1963) are from a past era. Today scant political weight is given to the civic value of this country’s physical plant. And yet, public buildings have not ceased to carry enormous cultural freight and communicate copious civic meaning.

Jumping geographic and cultural tracks: Though no longer functioning as a train station, as civic architecture the Old Seoul Station remains a politically and culturally potent structure. Designed by Tsukamoto Yasushi and finished in 1925, the station stood as both a product and a symbol of the Japanese occupation. While some civic buildings from this period were demolished, in 1947 the station was very practically renamed and continued to function as Seoul’s main rail hub until 2004 when Korail’s new Seoul Station* was completed. In 2011 the old station reopened as Culture Seoul Station 284, a cultural center with space for performances, exhibits and events. The name alludes to the station’s position as an intersection of historical, spatial, cultural and civic symbolism.

Corners (interview, review 1, 2), has undertaken a “Railway Library” of three books. The first book in this series is 경성역 (Gyeongseong Station). It is focused on a nuts and bolts representation of the Old Seoul Station. It begins with an essay, describing the physical building and the history of its construction and use, followed by a barebones timeline of the station from the construction of the first station building in 1900 through the renaming of the 1925 building in 1947. The blurb on Corner’s website describes using the railroad as a filter for critical cultural and historical examination.

Corners (interview, review 1, 2), has undertaken a “Railway Library” of three books. The first book in this series is 경성역 (Gyeongseong Station). It is focused on a nuts and bolts representation of the Old Seoul Station. It begins with an essay, describing the physical building and the history of its construction and use, followed by a barebones timeline of the station from the construction of the first station building in 1900 through the renaming of the 1925 building in 1947. The blurb on Corner’s website describes using the railroad as a filter for critical cultural and historical examination.

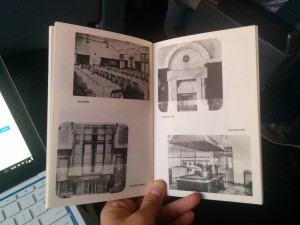

The meat of the book is archival photographs of the station that detail the ostentatious grandeur and Western influence of its multitudinous architectural styles. The building is clearly a statement. Like any colonial architecture, the function of the building was as much cultural and political as practical. The same can be said of the photographs. It is telling that only a single train appears in any of the photographs and then only incidentally; nor are there any photographs of any of the functional aspects of the building: switches, signals, or other mechanical infrastructure. There are only two photographs showing the tracks of the station; these are, like the single train, incidental to the architectural view behind them. The importance of the building was not in its function as transportation infrastructure but in its function as a cultural and political symbol.

We are shown the station as a particular set of physical facts; we are not shown the base function of the building or the complex web of human interaction that sustains it. It is a grand, modern and industrial physical fact. We do not see any planning sessions nor a groundbreaking ceremony. We do not see workers constructing the building nor installing the interior decoration. We do not see people manning (nor patronizing) the barber’s chair. We do not see people sitting down to dinner in the restaurant nor anyone in the kitchen preparing meals. With exception of the first and last photographs in the book we see no people; in these we are shown two crowds. In the first we see a crowd facing away seated inside the main dining room during the dedication or opening ceremony. In the second we see the hoi polloi stretching to Namdaemun and facing us; the caption ambiguously describes “citizens” filling the street outside the station without describing the purpose or occasion of their doing so. The cultural implications of this representation were certainly as intentional as the architecture itself.

We are shown the station as a particular set of physical facts; we are not shown the base function of the building or the complex web of human interaction that sustains it. It is a grand, modern and industrial physical fact. We do not see any planning sessions nor a groundbreaking ceremony. We do not see workers constructing the building nor installing the interior decoration. We do not see people manning (nor patronizing) the barber’s chair. We do not see people sitting down to dinner in the restaurant nor anyone in the kitchen preparing meals. With exception of the first and last photographs in the book we see no people; in these we are shown two crowds. In the first we see a crowd facing away seated inside the main dining room during the dedication or opening ceremony. In the second we see the hoi polloi stretching to Namdaemun and facing us; the caption ambiguously describes “citizens” filling the street outside the station without describing the purpose or occasion of their doing so. The cultural implications of this representation were certainly as intentional as the architecture itself.

Photographs are not simple carriers of absolute fact. Photographers make a host of decisions about what to record and how to do so. These photographs are not the simple documents that they purport to be. They are as much a depiction of the colonial system of which they are a functional aspect as the station they show. The decisions of what is shown and how it is shown are made by editors and designers as well. The designer, Jo Hyo Joon, made a conscious decision to use these particular photographs and to present them in the way that he has. It is an interesting decision to choose to situate a process of reconciliation or reclamation on such contested ground. It is as though Jo is letting us know that every square inch of the conversation will be contested ground.

Photographs are not simple carriers of absolute fact. Photographers make a host of decisions about what to record and how to do so. These photographs are not the simple documents that they purport to be. They are as much a depiction of the colonial system of which they are a functional aspect as the station they show. The decisions of what is shown and how it is shown are made by editors and designers as well. The designer, Jo Hyo Joon, made a conscious decision to use these particular photographs and to present them in the way that he has. It is an interesting decision to choose to situate a process of reconciliation or reclamation on such contested ground. It is as though Jo is letting us know that every square inch of the conversation will be contested ground.

Corner’s continued use of the Risograph printing process is another interesting choice. Taken in the first half of the twentieth century, the photographs in this book appear to have been shot and printed with a variety of techniques. The clipped corners suggest dry plate negatives (dry plate materials were certainly used by the Japanese authorities at this time). The odd shapes of some images suggest albumen prints, and silver gelatin materials were almost certainly used for the later photographs. These photographic processes create richly beautiful objects. The Risograph printing eliminates the differences between these techniques’ visual styles. They become artifacts; their creation as functional government documents is emphasized.

경성역 is not so much a book of photography as a book of political and cultural critique that uses photography to make its argument. It is clear that these photographs are telling us something about the world but it is up to the reader to examine these facts critically in order to come to terms with the Old Seoul Station and its past, present and future meaning in the fabric of Korean culture and history. The stage is set for additional books in the Railway Library.

디자인 : 조효준

년도 : 2014

출판사 : 코우너스

크기 : 12 x 18.8 cm

인쇄 : 리소그라프

제본 : 실 가격

*The new Seoul Station represents a contemporary example of exactly the kind of civic-minded architecture discussed above.

The New York Public Library has a wide-ranging (sprawling one might say) show up right now entitled “public eye“. The show, the first such large scale retrospective survey of photography undertaken by the NYPL, is intended to explore the ways in which photography is and has always been both widely shared and encouraged such sharing. The ubiquity of the medium and its ability to be transmitted has made it uniquely able to move ideas between locations and over time. Photography was a sharing medium before social media.

Of the numerous books in the show, three caught my eye as being relevant to this blog. In KPB’s review of Lee Deugyoung’s Two Faces I noted that his book referenced Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip. Ruscha’s book is included in the NYPL exhibit beside a similar book published in Japan in the mid-1950s: Ginza neighborhoods & eight subdivisions of Ginza by the photographer Yoshikazu Suzuki (edited by Kimura Shohachi and published in Tokyo by Toho-Shuppan in 1954). A few steps away was a book that predated Ruscha’s and Suzuki’s books by almost a century: Eadweard Muybridge’s 13 panel panorama of San Francisco (in book form).

What struck me seeing these three books and thinking of Lee’s book was the way that variations of a single form could emerge in such different times and places, drawn from such different concerns and used with such differing intents. The cross-pollination that occurs between cultures, over time and across distance is difficult to map or to measure.

There are almost certainly other such connections to be made from the NYPL’s show. A single point of connection opens one up to potentially numerous connections. “public eye” is well worth seeing if one is in New York City.

Last month KPB crossed the two year mark. Yea!

While posting has been been a little irregular the last couple of months, there are plenty of books in the queue and a couple of interviews in the works. I’m looking forward to the coming year.

Two weeks ago I was in Greece hopping from island to island. On the high speed catamarans that ferried us from port to port sea spray would drive against the windows of the cabin in which we were ensconced. We did not feel the spray nor smell the salt in the air. Skipping from beach to beach we were likewise ensconced in a fantasy of idyllic island living. We looked at a great many things, but hardly saw the lives of those around us. We did very little of the concerted looking that leads to seeing.

Oh Jin Tae’s Sound of Sea [sic] is the polar opposite. Continue reading

Printed Matter’s NY Art Book Fair opens this afternoon at MoMA’s PS1 (actually it opened last night with a VIP Preview).

Red Fox Press, several of whose books have been reviewed here, will be in attendance, and I’m looking forward to seeing Francis and Hye Mee again at this year’s fair.

Also exhibiting is the Seoul based Datz Press. This publisher is new to me. I can’t wait to meet them and to see what they’ve brought.

KPB is going on vacation. To Greece.

A couple of reviews are in the works and will go up on my return.

I’ll leave you with this photograph.