This review is late. Not because it was supposed to be last week’s missed post (or yesterday’s for that matter) but because I had intended to write about this book back in June immediately after the post on On The Line. That post was published the weekend that Memorial Day was observed here in the United States. On the Line‘s examination of the lasting impact of the still simmering Korean War presented photographer’s observations of the political, social, cultural and personal effects that the war has had.

While it is important to acknowledge that military conflict has a role in shaping the world (in a larger sense if not an immediate personal sense) and to acknowledge those who form these militaries, it would be a mistake to forget that there are plenty of tumultuous non-military events, national, local and personal that have shaped the current state of the world and more locally of Korea. Not all of these events are military. Some, certainly, are tied to the branches that spread from military conflicts, but many more are tied to broad struggles for individual autonomy and opportunity within national and local politics and economic structures. Much of this struggle has been by ordinary people, united.

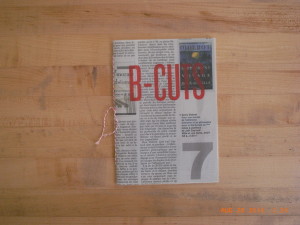

DongPhil Shin has traced the buds and branches of social upheaval that has marked Korea over the past decades. Documentary 1985-2005 brings together 5 discrete projects plus an overarching view of street protest in Korea in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s. Throughout these projects is a sense of the individual’s role in shaping larger narratives. At the root of any confrontation, social change or economic shift are individuals who march in the streets, pull lumps of rock from hillsides, maintain and affirm that “this is what I believe” or simply live their lives day by day.

Shin’s photographs are starkly documentary in form while constantly laying bare his own social and political views. At first glance they would appear to be pulled from newspaper or magazine articles (and indeed they may have first been published in these outlets). They are, however, more than simply journalistic images meant to feed a hungry and fickle press. Shin studied philosophy before studying photography. His photographs are intensely personal and mine a deeper emotional current that runs beneath their surface and of the social fabric which they depict.

Bong-Lim Choi, in the book’s introductory text, describes Shin’s photography as “evocations of the imperialism, capitalism and authorization [sic] rules that completely deprived the public of their individual life [sic].” His photographs are angry even when they are quiet. Taking the “suffocating age of oppression” as their subject, the photographs depict those under the boot of history taking defiantly to the street or maintaining a quiet quotidian dignity through their suffering.

On the flap of the dustjacket is a portrait of Shin. He gently cradles his Mamiya 7 with Metz flash against his chest. A Contax G2 hangs from his shoulder. He stares coolly out at the viewer. A two tone wall is behind him–though half of it dissolves to nothing. His face and clothing is covered in the soot of the street. The portrait perfectly encapsulates Choi’s closing thoughts from his introductory text: social engagement is critical to Shin’s sense of humanity and that his photographs adopt an ideological standpoint shared by, in his view, the majority of our society. Shin’s photographs are as much participants in the upheaval that they depict as they are a documentation.

The book begins and ends with photographs of street protests–both close and personal and pulled back to abstract crowds. These opening and closing images announce Shin’s intentions. The five projects book ended by these sets of street protest photographs bring into focus personal stories that lay bare the wounds inflicted by an imperfect world; it is this world that the protests are aiming to change for the better. (Nearly a decade on from the last image being made, there is a fair debate to be had on whether or not the improvements sought have been achieved and what opportunities, if any, were missed. This review will steer clear of making any such historical judgement.)

The five series are: People Who Didn’t Change Their Political Faith and Went Back to North Korea; A Coal Town; A School in Japan Run by the Pro-North Korean Residents’ League in Japan; Korean Victims of the Atomic Bomb; and The Korean Residents in Kyoto. One photograph from each:

People Who Didn’t Change Their Political Faith and Went Back to North Korea: A elderly man lays in bed en-robed in quilts, blankets and bedding. A pool of light, like a death mask, illuminates his face, catching on the gray hair at his temples and his white beard. His clothing has fallen off of his left shoulder, which is bare. He looks up and out of the frame. It is hard to read his emotion: disappointment? expectation? hope? stoic resignation? regret?

A Coal Town: A man sits eating lunch. He is shirtless. A yellow plastic miner’s helmet is perched on his head, its lamp illuminating his lunch. The flash of the camera separates him from the dark tunnel stretching out behind him. A pair of railroad tracks lead back into the gloom. This could be any ajashi anywhere in Korea taking a break for lunch save for the setting. The darkness is all encompassing except the pool of light the miner sits in.

A School in Japan Run by the Pro-North Korean Residents’ League in Japan: Four students sit at their desks besides windows. The windows have been blocked with newspapers to block the glare of sunlight (?). The students are bent over school work that they are writing out in notebooks. Their bags hang beside their desks. There is light outside the windows, but it is muted, grayed, and blocked by the newspapers’ printed text. The light is mediated. (On the following page three students look out an opened window. It is not blocked with newspapers. They all smile at the photographer. One girl pokes her head out of the window and into the light, wind sweeps through loose strands of her hair.)

Korean Victims of the Atomic Bomb: An older middle aged man sits cross legged on the floor; he faces to his right exposing his left side to the camera. Behind him is a wall papered with a floral pattern. A soft gray infuses the photograph; a light from the right illuminates a scar that runs down his side. The man’s hair is disheveled. His eyes look down and away. There is stubble on his face. His expression is not pained but shows the trace of pain long endured.

The Korean Residents in Kyoto 1987 – 2004: a man, his eyelids heavy and drooping, almost closed, sits on a pile of blankets. His face is in luminous shade. He is warming his hands over an electric hot plate or small gas grill. A suit and white shirt are hanging on the pull of an armoir behind him. Through the glass panes of the door we can see towels or blankets. Kitchen utensils clutter the left foreground. From the right a draped window casts a soft gray light across the scene.

The protest picture that closes the book: Night time; a large public square seen from above. We are looking down on a field of myriad light sources–candles most likely. Each is held by a person though we cannot see the people in the dark of the night except a few silhouettes or along the periphery of the crowd where it comes beside a major roadway’s street lights. What we see is the light that they bring: hope, determination, belief, willingness to action.

As the world seems to be fragmenting and falling apart today before our very eyes in the newspapers and on the news channels, Shin’s photographs remind of us two things: it is real people who bear the brunt of suffering and it is the union of individuals acting in concert that brings about change. In the photographs light becomes a halo or a salve for those who have been wronged and points like an arrow so that the viewer might see. Light, too, is held by the individual and in the massing of individuals it fills the frame with light. DongPhil Shin wields his camera like a torch; he is not so much recording light as directing it with a political eye towards illuminating the imperialist, capitalist and authoritarian wrongs that the State has brought to bear on individuals. Shin shows not only the wrongs that have been wrought but also offers a path of action for ameliorating these wrongs–at the center of both is the individual.

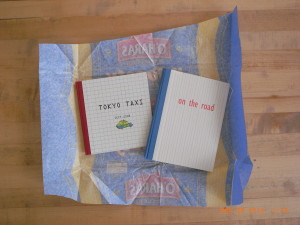

Documentary

Photographer: DongPhil Shin

Essay: Bong-Lim Choi

Publisher: Cana Books

Copyright DongPhil Shin 2006

Addendum:

Collecting Side Note

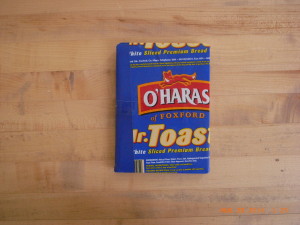

While I usually shop for Korean photo books in Korea (obviously), I happened across this book in Alabaster Books, a small New York book shop on 4th Avenue. I was killing time between appointments and stopped into the shop on a whim. As I set down a collection of A.D. Coleman essays I noticed the Korean lettering on the spine of Documentary. I haggled a little with the proprietor on the price and then bought the book.

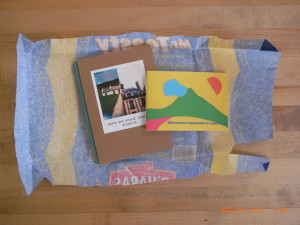

Flipping through the book later I came across a handful of details that lay out a provenance to the book that make it moderately interesting as a historical object, though they certainly don’t make it valuable.

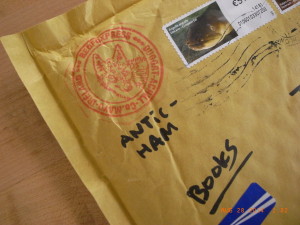

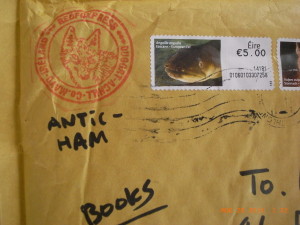

Tucked into the title page is a shipping label. This copy of the book was sent by the photographer to the “Stefan Stux Gallery”. I assume the book was part of a submission by the photographer to the gallery.

Below the colophon is a stamp with a handwritten edition number (83/200) with a red stamp over this (it appears to be the photographer’s stamp). The quality of the printing suggests that the book was probably printed in a larger edition than 200 (though I could certainly be wrong), and I wonder if this book hadn’t originally accompanied a print as a sort of special edition.

At the back of the book, in the margin of the profile/C.V. of the photographer is a hand drawn self portrait of the photographer in ink.

It is discovering small details like this that make seeking and collecting fun.