Bright Shadow opens with a photograph of the Mongolian steppe. The horizon line is low in the frame, marked by mountains in the blue distance. The brown of dry grassland stretches out to meet the mountains. The land is receding; it is falling out of focus. A cloud filled blue sky dominates the picture, or would if a pair of truck mirrors in the foreground weren’t breaking the frame. The mirrors mar and distort the steppe caught in their surfaces.

We come to the city. It is seared by sunlight. The sky is blue and dark. There is no ground; buildings seem to sprout from their own concrete. A billboard advertising an apartment complex, still under development, promising elegance and luxury, dominates the photograph. We are in Mongolia.

A bolt of yellow: a woman in a yellow shirt and large white sunglasses is transformed by the photographer’s flash, which overpowers the sun. The background is dark (a trick of balancing the ambient and flash exposures in favor of the flash). More portraits of people picked out of their surroundings by the photographer’s flash follow: a middle aged, large bellied, man in a dress shirt; security guards; a young man with a hip haircut and popped collar; three young women, one looking away; two soldiers in their fatigues; a rancher in his chaps; construction workers; businessmen (or gangsters). The portraits are full of strong color and hard light. They bring to mind Hein Kuhn Oh’s ajumma portraits as well as Philip Lorca Dicorcia’s strobe lit street portraits and Bruce Gilden’s aggressive street photography.

The portraits are interrupted by a series of full bleed double truck urban landscapes in grainy black and white. Cars commingle. Cranes loom over rising buildings. A fountain’s spray dissipates into a gust of wind. The flash lit portraits continue: a man in uniform; a young man, hip; a young couple; a boy and a teen.

And then there comes a break: a black and white portrait of a young girl in some sort of costume–Mongolian? Korean? Play?. A second black and white portrait follows: an older, heavy set Native American woman with blotchy skin and thick fingers. Another portrait, this one in color: a Native American woman (neither young nor old) who looks away from the camera. We return to black and white: another woman, cropped tightly, her collar bones and upper chest are bare. And then color: a stark portrait of a Korean woman wearing a nurses uniform sitting before an off-white wall and staring intently into the lens. Three Korean boys look uneasily into the camera. A Mongolian family, four people covering three generations, stands on a plaza before what appears to be a government building; they stand erect. The husband’s face is marked with anxiety; he pulls his son in towards himself. The son looks off to his left away from the camera. The mother smiles; there is pride mixed with bemusement. The grandmother, leaning on her cane, wears a traditional costume with two government medals pinned to it. She looks towards the lens but not into it–perhaps she is looking beyond it. This family is followed by a group portrait of Korean healthcare workers; or maybe they are Mongolian.

The book ends with a final portrait: a tightly cropped photograph of an older Native American woman’s softly lit, wrinkle-etched, face. Her eyes are moist. In them we see the photographer’s reflection.

Interspersed throughout the book are roughly printed pages with multiple black and white documentary photographs. They are not only of Mongolians but also of the Korean diaspora and Native Americans. They depict daily life, rituals, landscapes, and portraits. In these mash-ups Sohn plays his hand.

When I say that Sohn has played his hand, I mean that this book engages his broader interest in the historical, societal and economic stories of the Mongoloid race told through the visual arts. (This is paraphrased from his bio. As this parenthetical note probably makes clear, I am uncomfortable with the word “Mongoloid”.) Sohn’s work is interpretive rather than documentary. Though this book is ostensibly about the effects of rapid economic expansion in Mongolia, the mash-ups and closing sequence present tangential forays into origin myths, the Korean Diaspora, racial affiliation and historical or colonial injustices. How could one talk about the effect of rapid economic expansion without also speaking to these other ideas? They feed one another.

As noted in Kay Jun’s essay that concludes the book, Sohn is both a photographer and an anthropologist by training. His previous books, The Circle Never Ends and Close Encounters of the Fourth World, pair photographs with essays and seek to bring into the light the stories of Native Americans. In “Bright Shadow” Sohn drops all text and “attempt[s to] touch on [the] complexity of history of humanity only through the prism of photographed images” according to Kay. This is a particularly photographic endeavor, and one that steps away from an objective stance. This is apparent from the first image of the out of focus landscape that comes into focus in the mirrors’ reflections. Though in focus, this reflection is distorted by the curves of the mirror. With this opening, Sohn is stating that he is no more objective than the mirrors. His perspective and his interests inform (or distort) what is before his camera.

Sohn is entirely transparent in this. His camera is not invisible. Instead, it makes itself known in the pop of the flash. The portraits are stories that build within a larger Story. When we come to the crux of the narrative, rapid economic development creating unforeseen societal consequences, we shift into black and white. Our world goes gritty. When we’re following his free associates between parallel stories not only does the aesthetic style shift into a traditional documentary mode but also the paper selection, printing and design shifts. These shifts are too rapid in the final sequence where they feel awkward, heavy handed. I find that the ending presents a tangle compared with the puzzle that the rest of the book puts forth.

As an object, Bright Shadow is lovely. It’s cover boards are beautifully wrapped in some kind of rice (?) paper with metallic flecks. The cover is bare except for the Aprilsnow Press logo embossed in the lower right corner. The photographer’s name, the book’s title and the publisher’s name are embossed on the spine. The printing quality is very good. The design is sparse and yet entirely appropriate to the themes that run through the book. There a few design flourishes such as the red, yellow and black ribbon page markers. Kay’s essay is enlightening, if not perfectly translated. There is a discussion between Sohn, Lee Young June and Kim Nam Soo, as well, though it is not translated into English.

Much like Jaeyu Lee’s Fragments in Scene, I find this book a wonderful agglomeration of anthropological process and visual communication. While it is highly conceptually driven like much contemporary Korean photography, Sohn’s integration of cross-practice methodologies and reliance on purely visual storytelling (leaving aside Kay’s essay and the discussion) gives the viewer rich opportunities to make broad connections and find their own insights from the work. It’s conceptual drive is expansive rather than reductive. In the end, this overwhelms the book, which falls apart in its final sequence. None-the-less, it is an interesting and engaging book.

Bright Shadow

Sohn Sung Hyun

texts: Sohn Sung Hyun, Lee Young June, Kim Nam Soo, Kay Jun

Edited and Designed by Kay Jun, Jeong Jae Wan

Proofread by Kang Young-gyu

Translated by Angelina Gieun Lee

Transcribed by Lee Hyunsong

Printing and Binding by Munsund Printing

Published by Aprilsnow Press

2013

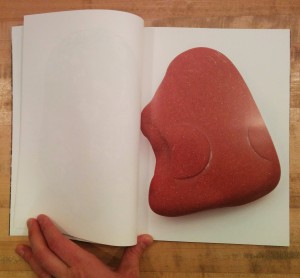

Let’s start with the conclusion: Kyoungtae Kim’s On the Rocks is an amusing, clever and honest book but not a grand one. That conclusion can be drawn from its subject matter: close-up macro photographs of small, everyday stones–roughly 2cm to 10cm in length. The bulk of the book is single pages in which each stone, floating in studio limbo, is enlarged to fill the page. Every singular stone is richly textured, wonderfully abstract and evocative–and yet humdrum.

Let’s start with the conclusion: Kyoungtae Kim’s On the Rocks is an amusing, clever and honest book but not a grand one. That conclusion can be drawn from its subject matter: close-up macro photographs of small, everyday stones–roughly 2cm to 10cm in length. The bulk of the book is single pages in which each stone, floating in studio limbo, is enlarged to fill the page. Every singular stone is richly textured, wonderfully abstract and evocative–and yet humdrum. Those three facts make me think the book came out of two questions: 1. When I travel to Europe, what can I bring back with me? 2. Now that I’ve got all these stones and pebbles sitting around, what can I do with them?

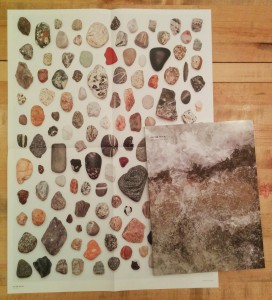

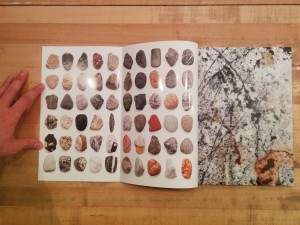

Those three facts make me think the book came out of two questions: 1. When I travel to Europe, what can I bring back with me? 2. Now that I’ve got all these stones and pebbles sitting around, what can I do with them? The photographs are also placed in grids in which the stones are seen relative to one another. On the inside covers, the stones are scaled to a single uniform size and printed in grids. In a nice touch, one must open the inside flap of the cover (onto which the full bleed cover image does not extend) to reveal the grids. A similar gridded spread follows the colophon page; on this grid the stones are scaled relative to one another and there is a scale so that one can determine how large each stone is in reality. This grid is repeated on a pull out poster on which the stones are printed life size (at 1:1 scale).

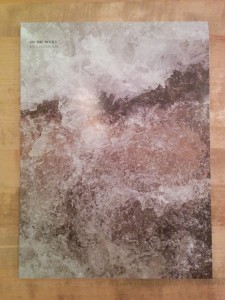

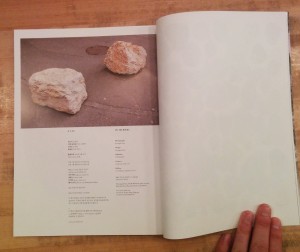

The photographs are also placed in grids in which the stones are seen relative to one another. On the inside covers, the stones are scaled to a single uniform size and printed in grids. In a nice touch, one must open the inside flap of the cover (onto which the full bleed cover image does not extend) to reveal the grids. A similar gridded spread follows the colophon page; on this grid the stones are scaled relative to one another and there is a scale so that one can determine how large each stone is in reality. This grid is repeated on a pull out poster on which the stones are printed life size (at 1:1 scale). There is one outlier image. At the top of the colophon page is a photograph of two rocks sitting heavily on a paved street. These are rocks not stones. They’re large, roughly a meter square. This is entirely unlike any other photograph in the book and yet this photograph is the key stone supporting the entire structure or the rosetta stone that rearranges our understanding of the preceding photographs. We have spent the book looking and looking at these small stones as aesthetic objects divorced from any context. In this one image we are brought back into the world. We are shown two rocks. They have not been made by the photograph into anything more than they are. And yet one’s first impulse is to lean in close to look at them, to examine them. What magic is hidden in these most quotidian of objects?

There is one outlier image. At the top of the colophon page is a photograph of two rocks sitting heavily on a paved street. These are rocks not stones. They’re large, roughly a meter square. This is entirely unlike any other photograph in the book and yet this photograph is the key stone supporting the entire structure or the rosetta stone that rearranges our understanding of the preceding photographs. We have spent the book looking and looking at these small stones as aesthetic objects divorced from any context. In this one image we are brought back into the world. We are shown two rocks. They have not been made by the photograph into anything more than they are. And yet one’s first impulse is to lean in close to look at them, to examine them. What magic is hidden in these most quotidian of objects?