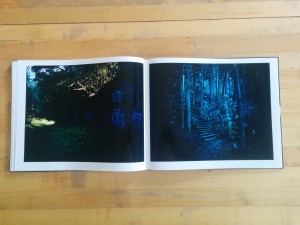

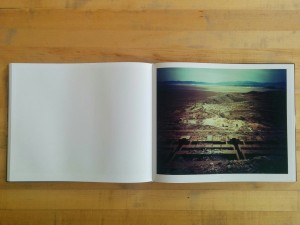

Photographing at night exposes the world in a new light. We are able to see things in ways that we cannot during daylight hours. Taewon Jang has gone out into the darkness to photograph stalled construction projects, remnants of abandoned factories and the nocturnal glow of functioning industrial sites so that we can see them, literally, in a different light.

Photographing at night exposes the world in a new light. We are able to see things in ways that we cannot during daylight hours. Taewon Jang has gone out into the darkness to photograph stalled construction projects, remnants of abandoned factories and the nocturnal glow of functioning industrial sites so that we can see them, literally, in a different light.

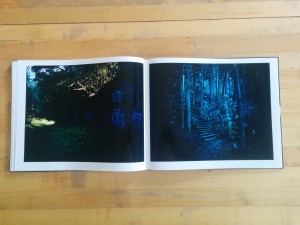

The light of the night is the opposite of the light of day. Daylight is external and falls onto the world–and does so with relative equality. At night, light jets outward from the subjects and pools close to its source leaving the rest of the world dark. By photographing at night–and by making use of the long exposures required by his large format camera, Jang traces the power relations (literal and metaphorical) of contemporary society.

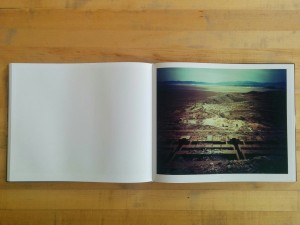

Jang began making photographs in Korea and Japan of stalled construction sites. Over the seven year period during which he photographed, he expanded his subject matter to include abandoned factories and functioning industrial sites as well as expanded his geographic area to include the United States. In total, he has photographed almost 400 different sites. Seventy-seven of these appear in Stained Ground.

Jang began making photographs in Korea and Japan of stalled construction sites. Over the seven year period during which he photographed, he expanded his subject matter to include abandoned factories and functioning industrial sites as well as expanded his geographic area to include the United States. In total, he has photographed almost 400 different sites. Seventy-seven of these appear in Stained Ground.

Distilling physical objects and their complex outer appearances into photographic form gave way to seeking evidence of the deep structures of our social contract. What is interesting is how the subjects suggest not only the social developments that begat them but also the continual development that will later consign them to obsolescence.

He describes the way his subjects evolved over the course of the seven year project in an interview with Suejin Shin included in the book: “In the beginning, I concentrated on the specific topography or the architecture, or perhaps a structure, or construction equipment, thinking that these elements could reveal the strange tension I felt at the site[s]… But then as I continued working on this project for a long time, I came to realize that what I saw was only a very small part of a larger picture… the places I photographed have changed beyond recognition or have even vanished from the map.”

He describes the way his subjects evolved over the course of the seven year project in an interview with Suejin Shin included in the book: “In the beginning, I concentrated on the specific topography or the architecture, or perhaps a structure, or construction equipment, thinking that these elements could reveal the strange tension I felt at the site[s]… But then as I continued working on this project for a long time, I came to realize that what I saw was only a very small part of a larger picture… the places I photographed have changed beyond recognition or have even vanished from the map.”

The light that illuminates these subjects and suffuses the photographs with an ethereal glow is itself a product of the development that these photographs trace. Likewise, Jang’s ability to photograph is a product of the development. Without the progress of the first and second industrial revolutions (and that continues in the third industrial–or technological, revolution of the present day) these photographs could not exist and their subjects would not exist. The advancements of each revolution bring about new technologies and new industries while leaving behind the old and setting the foundation for the next.

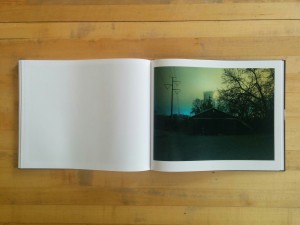

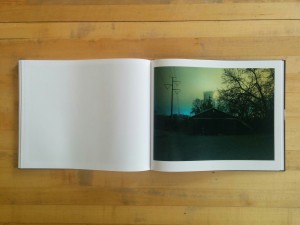

The last three photographs of Stained Ground can be read as a coda for understanding the book: In “SG U #415, 2013”, a vast windfarm spreads across the frame. Each windmill is marked off by the red glow of its warning light. The movement of some of the turbines’ blades over the course of the long exposure has blurred them into nothingness. In the background a miasma of green light sets off the dark and skewed horizon. Our own technology appears as “other.” The scene suggests both a technological miracle and an apocalypse brought about by the chain of changes these machines are intended, at least in part, to solve. The next photograph, “SG U #321, 2007,” is of a small, low industrial building. It’s garage door is dark but open–we can see the dim form of a white chair inside. To the right, the bare spindly branches of a tree loom over the building as if about to collapse onto it.  In the background the cooling towers of a power plant hover in a haze of brackish yellow clouds. Running from the foreground to the background in the left of the frame are high-tension power lines. They run straight back to a patch of blue cloud along the far horizon. The path to our current state has run along a line of iterative steps. Each successive revolution has brought the next. Photographically, the book ends with “SG K #420, 2007”. This photograph is one of only a handful that includes people and is the only photograph in which people are central. A group of 9 men (I assume they are men) are in a line in the center of the frame. They are dwarfed by the night around them. Five stand while four crouch or sit huddled on the ground. A line of hills run along the horizon and are dark against a multicolored sky. The ground on which the men are set is orange and indistinct. It is unclear if this is where perhaps some original industrial beginning occurred or where and how we’ll be left at some point in the future after our industry has run us to ground.

In the background the cooling towers of a power plant hover in a haze of brackish yellow clouds. Running from the foreground to the background in the left of the frame are high-tension power lines. They run straight back to a patch of blue cloud along the far horizon. The path to our current state has run along a line of iterative steps. Each successive revolution has brought the next. Photographically, the book ends with “SG K #420, 2007”. This photograph is one of only a handful that includes people and is the only photograph in which people are central. A group of 9 men (I assume they are men) are in a line in the center of the frame. They are dwarfed by the night around them. Five stand while four crouch or sit huddled on the ground. A line of hills run along the horizon and are dark against a multicolored sky. The ground on which the men are set is orange and indistinct. It is unclear if this is where perhaps some original industrial beginning occurred or where and how we’ll be left at some point in the future after our industry has run us to ground.

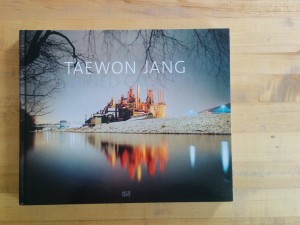

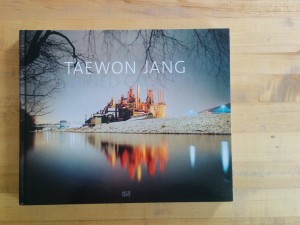

This is beautiful work and powerfully moving–in spite of the book’s humdrum design. As an object, Stained Ground is disappointing. As a point of comparison with another recent Hatje Cantz, Bae Bien-U’s Windscape‘s design pays attention to small details like the use of different papers for the text and plates and the use of a translucent matte dust-jacket that evokes the soft light of the photographs within. By comparison, Stained Ground lacks these small book maker’s touches. The cover is a good example of this: it is a garish glossy wrap with the title lost in the tones of the photograph over which it is set. Looking at Jang’s previous book, Black Midday, one sees a somewhat lower production value but a significantly greater attention to the design.

Stained Ground is a nice book to have on the shelf but not a necessary one. It doesn’t elicit delight. While it may seem odd to suggest that this should be the goal of a book whose subject matter is so somber, art books ought to be as much an object of delight as a carrier of content. One could imagine and certainly desire that design might have better served as mirror and amplifier to the content of Stained Ground. None of this is meant to discount the power of the photographs which are necessary and ought to be seen.

Stained Ground

Taewon Jang (site)

Edited by Suejin Shin and Markus Hartmann

Copyediting: Leina Gonzalez

Graphic Design and Typesetting: Andreas Platzgummer, Hatje Cantz

Production: Nadine Schmidt, Hatje Cantz

Typeface: Thesis, The Sans

Reproductions: Jan Scheffler, prints professional

Paper: Galaxi Keramik

Printing and Binding: DZA Druckerei zu Altenberg GmBH, Altenberg

2014

***

A brief post-script: A couple of American photographers making work contemporaneously with Jang are brought to mind by this book. Jang’s “SG U #405, 2013” recalls Mitch Epstein’s, American Power (as well as State of the Union, also published by Hatje Cantz). Epstein’s photographs examine the relationship of American society with industry, primarily in the form of energy production. Epstein places industry as ever present in the background of everyday life. Industry is there, but it remains, just barely, secondary to the human lives that it supports. Like Jang, his photographs are hesitant in passing judgement but present a troubling view. Less ambivalent is Will Steacy. Like Jang, Steacy spent long nights photographing America at night with a large format camera. In Down These Mean Streets, Steacy brought an agitprop sensibility to depicting the plight of the American City–in its archetypal and specific forms. The light in Jang’s photographs may hint at apocalypse and dystopia, but it has none of Steacy’s firebrand anger.

My last visit to Seoul came at an interesting time. My own country had just elected an orange-hued charlatan (but much loved by some, apparently) to its highest office, sparking immediate protests. Seoul was in the midst of weekly and growing protests each Saturday against an expanding presidential scandal. And multiple elections were approaching in Europe with right-wing parties gaining ground in polls. There are many people marching in the streets lately who want to see change. With all of this as a background, I came across Park Seung-hwa’s Protest published by Listen to the City in The Book Society’s stacks.

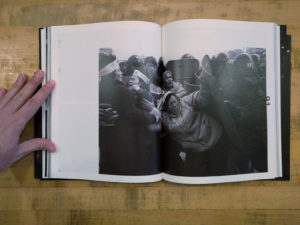

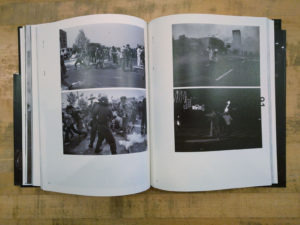

My last visit to Seoul came at an interesting time. My own country had just elected an orange-hued charlatan (but much loved by some, apparently) to its highest office, sparking immediate protests. Seoul was in the midst of weekly and growing protests each Saturday against an expanding presidential scandal. And multiple elections were approaching in Europe with right-wing parties gaining ground in polls. There are many people marching in the streets lately who want to see change. With all of this as a background, I came across Park Seung-hwa’s Protest published by Listen to the City in The Book Society’s stacks. The photographs run the gamut from dramatic confrontation to quiet determination. There are individuals acting alone and huge crowds of people acting in concert. We are shown moments of grace and moments of violence. On one page protesters look down from a rooftop at the police below. On the next page it is the police who are on the roofs looking down on the people below. The one constant is a sense of confrontation and anger, at turns explosive and subdued. The content of the photographs is mirrored by the divided compositions in contrasty and grainy yet richly rendered black and white.

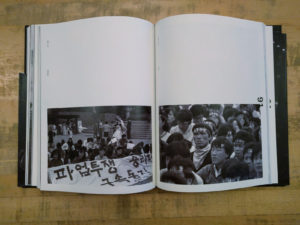

The photographs run the gamut from dramatic confrontation to quiet determination. There are individuals acting alone and huge crowds of people acting in concert. We are shown moments of grace and moments of violence. On one page protesters look down from a rooftop at the police below. On the next page it is the police who are on the roofs looking down on the people below. The one constant is a sense of confrontation and anger, at turns explosive and subdued. The content of the photographs is mirrored by the divided compositions in contrasty and grainy yet richly rendered black and white.  Park draws from his own work as well as the work of the four other photographers who formed the National Photography Research Society (민족사진연구회). These five photographers, Kwon San-Ki, Park Seung-hwa, Song Hyeok, Lee Sohye, Lim Seok Hyun, came together photographing the protests. They gathered around an older photographer, Park Yong-su. Their efforts, specifically as culminated in the publication ofProtest, are a kind of extension of Park Yong-su’s 1989 book The Road of the People (민중의 길), in which he documented the events between the 1985 sit-in demonstration at the American Cultural Center in Seoul and Chun Doo-hwan’s going to Baekdamsa in 1988. Despite this added context, a straight documentary reading remains problematic.

Park draws from his own work as well as the work of the four other photographers who formed the National Photography Research Society (민족사진연구회). These five photographers, Kwon San-Ki, Park Seung-hwa, Song Hyeok, Lee Sohye, Lim Seok Hyun, came together photographing the protests. They gathered around an older photographer, Park Yong-su. Their efforts, specifically as culminated in the publication ofProtest, are a kind of extension of Park Yong-su’s 1989 book The Road of the People (민중의 길), in which he documented the events between the 1985 sit-in demonstration at the American Cultural Center in Seoul and Chun Doo-hwan’s going to Baekdamsa in 1988. Despite this added context, a straight documentary reading remains problematic.  Park’s introduction to Protest is helpful in reframing these photographs. He reveals that the contemporary making of the book, was an effort to “uncover [his] faded passion and shell of belief” represented by photographs made over two decades earlier. These photographs are personal. They project “a kind of political intention” and come from a “‘biased’ point of view.” The photographs are at once “records, commemorations and, in a way, propaganda.”

Park’s introduction to Protest is helpful in reframing these photographs. He reveals that the contemporary making of the book, was an effort to “uncover [his] faded passion and shell of belief” represented by photographs made over two decades earlier. These photographs are personal. They project “a kind of political intention” and come from a “‘biased’ point of view.” The photographs are at once “records, commemorations and, in a way, propaganda.” Protest then is a lament or reckoning rather than a dry documentation. It is a sober reconsideration of that time and where the flow of time has ultimately led. Despite having “walked so far away from the days of the photos…the day [Park] has dreamed of during those old days has yet to come.” He asks that the there be no mention of a “legendary saga” when reading these photos and notes that “the past [is] often glorified under the astute compromise.” We all, in order to live our lives in some measure of comfort, make compromises in our beliefs and actions; Park subtly suggests that if we are honest with ourselves, perhaps our compromises are really betrayals of our convictions.

Protest then is a lament or reckoning rather than a dry documentation. It is a sober reconsideration of that time and where the flow of time has ultimately led. Despite having “walked so far away from the days of the photos…the day [Park] has dreamed of during those old days has yet to come.” He asks that the there be no mention of a “legendary saga” when reading these photos and notes that “the past [is] often glorified under the astute compromise.” We all, in order to live our lives in some measure of comfort, make compromises in our beliefs and actions; Park subtly suggests that if we are honest with ourselves, perhaps our compromises are really betrayals of our convictions.  In a similar vein, the book presents a kind of critique of photo-journalism and documentary photography. Park defines photographs as a “record of facts.” And yet he goes on to say that a myriad of photos can be created of a single scene. “These photos are all based on facts but far away from the truth.” Park does not claim to be publishing any kind of definitive view of these events. He goes so far as to call attention to the other photographers who were photographing these same events and whose photographs, if they could have been included in the book, would have made for “a finer and richer record.”

In a similar vein, the book presents a kind of critique of photo-journalism and documentary photography. Park defines photographs as a “record of facts.” And yet he goes on to say that a myriad of photos can be created of a single scene. “These photos are all based on facts but far away from the truth.” Park does not claim to be publishing any kind of definitive view of these events. He goes so far as to call attention to the other photographers who were photographing these same events and whose photographs, if they could have been included in the book, would have made for “a finer and richer record.”  These photographs and Park’s view of their creation and value are appropriate to consider here in America in light of the protests happening in the present day. As may be self evident but certainly worth reiterating: protest in and of itself won’t bring about change. Those bodies in the streets lifting their voices may create the changes they seek or may simply gratify their desire to speak their piece. In order to effect change there must be concrete political action being taken before and after the marches, protests and demonstrations. Desiring change does not necessarily create change. It requires long years of hard work. It is equally likely that in thirty years we will look back and wonder where it all got them. Compromises for our own comfort will leave us “wandering around, or rather drifting away.”

These photographs and Park’s view of their creation and value are appropriate to consider here in America in light of the protests happening in the present day. As may be self evident but certainly worth reiterating: protest in and of itself won’t bring about change. Those bodies in the streets lifting their voices may create the changes they seek or may simply gratify their desire to speak their piece. In order to effect change there must be concrete political action being taken before and after the marches, protests and demonstrations. Desiring change does not necessarily create change. It requires long years of hard work. It is equally likely that in thirty years we will look back and wonder where it all got them. Compromises for our own comfort will leave us “wandering around, or rather drifting away.”

Corners (

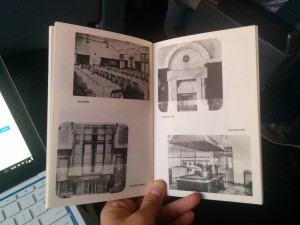

Corners ( We are shown the station as a particular set of physical facts; we are not shown the base function of the building or the complex web of human interaction that sustains it. It is a grand, modern and industrial physical fact. We do not see any planning sessions nor a groundbreaking ceremony. We do not see workers constructing the building nor installing the interior decoration. We do not see people manning (nor patronizing) the barber’s chair. We do not see people sitting down to dinner in the restaurant nor anyone in the kitchen preparing meals. With exception of the first and last photographs in the book we see no people; in these we are shown two crowds. In the first we see a crowd facing away seated inside the main dining room during the dedication or opening ceremony. In the second we see the hoi polloi stretching to Namdaemun and facing us; the caption ambiguously describes “citizens” filling the street outside the station without describing the purpose or occasion of their doing so. The cultural implications of this representation were certainly as intentional as the architecture itself.

We are shown the station as a particular set of physical facts; we are not shown the base function of the building or the complex web of human interaction that sustains it. It is a grand, modern and industrial physical fact. We do not see any planning sessions nor a groundbreaking ceremony. We do not see workers constructing the building nor installing the interior decoration. We do not see people manning (nor patronizing) the barber’s chair. We do not see people sitting down to dinner in the restaurant nor anyone in the kitchen preparing meals. With exception of the first and last photographs in the book we see no people; in these we are shown two crowds. In the first we see a crowd facing away seated inside the main dining room during the dedication or opening ceremony. In the second we see the hoi polloi stretching to Namdaemun and facing us; the caption ambiguously describes “citizens” filling the street outside the station without describing the purpose or occasion of their doing so. The cultural implications of this representation were certainly as intentional as the architecture itself.  Photographs are not simple carriers of absolute fact. Photographers make a host of decisions about what to record and how to do so. These photographs are not the simple documents that they purport to be. They are as much a depiction of the colonial system of which they are a functional aspect as the station they show. The decisions of what is shown and how it is shown are made by editors and designers as well. The designer, Jo Hyo Joon, made a conscious decision to use these particular photographs and to present them in the way that he has. It is an interesting decision to choose to situate a process of reconciliation or reclamation on such contested ground. It is as though Jo is letting us know that every square inch of the conversation will be contested ground.

Photographs are not simple carriers of absolute fact. Photographers make a host of decisions about what to record and how to do so. These photographs are not the simple documents that they purport to be. They are as much a depiction of the colonial system of which they are a functional aspect as the station they show. The decisions of what is shown and how it is shown are made by editors and designers as well. The designer, Jo Hyo Joon, made a conscious decision to use these particular photographs and to present them in the way that he has. It is an interesting decision to choose to situate a process of reconciliation or reclamation on such contested ground. It is as though Jo is letting us know that every square inch of the conversation will be contested ground.  Photographing at night exposes the world in a new light. We are able to see things in ways that we cannot during daylight hours. Taewon Jang has gone out into the darkness to photograph stalled construction projects, remnants of abandoned factories and the nocturnal glow of functioning industrial sites so that we can see them, literally, in a different light.

Photographing at night exposes the world in a new light. We are able to see things in ways that we cannot during daylight hours. Taewon Jang has gone out into the darkness to photograph stalled construction projects, remnants of abandoned factories and the nocturnal glow of functioning industrial sites so that we can see them, literally, in a different light.  Jang began making photographs in Korea and Japan of stalled construction sites. Over the seven year period during which he photographed, he expanded his subject matter to include abandoned factories and functioning industrial sites as well as expanded his geographic area to include the United States. In total, he has photographed almost 400 different sites. Seventy-seven of these appear in Stained Ground.

Jang began making photographs in Korea and Japan of stalled construction sites. Over the seven year period during which he photographed, he expanded his subject matter to include abandoned factories and functioning industrial sites as well as expanded his geographic area to include the United States. In total, he has photographed almost 400 different sites. Seventy-seven of these appear in Stained Ground. He describes the way his subjects evolved over the course of the seven year project in an interview with Suejin Shin included in the book: “In the beginning, I concentrated on the specific topography or the architecture, or perhaps a structure, or construction equipment, thinking that these elements could reveal the strange tension I felt at the site[s]… But then as I continued working on this project for a long time, I came to realize that what I saw was only a very small part of a larger picture… the places I photographed have changed beyond recognition or have even vanished from the map.”

He describes the way his subjects evolved over the course of the seven year project in an interview with Suejin Shin included in the book: “In the beginning, I concentrated on the specific topography or the architecture, or perhaps a structure, or construction equipment, thinking that these elements could reveal the strange tension I felt at the site[s]… But then as I continued working on this project for a long time, I came to realize that what I saw was only a very small part of a larger picture… the places I photographed have changed beyond recognition or have even vanished from the map.”  In the background the cooling towers of a power plant hover in a haze of brackish yellow clouds. Running from the foreground to the background in the left of the frame are high-tension power lines. They run straight back to a patch of blue cloud along the far horizon. The path to our current state has run along a line of iterative steps. Each successive revolution has brought the next. Photographically, the book ends with “SG K #420, 2007”. This photograph is one of only a handful that includes people and is the only photograph in which people are central. A group of 9 men (I assume they are men) are in a line in the center of the frame. They are dwarfed by the night around them. Five stand while four crouch or sit huddled on the ground. A line of hills run along the horizon and are dark against a multicolored sky. The ground on which the men are set is orange and indistinct. It is unclear if this is where perhaps some original industrial beginning occurred or where and how we’ll be left at some point in the future after our industry has run us to ground.

In the background the cooling towers of a power plant hover in a haze of brackish yellow clouds. Running from the foreground to the background in the left of the frame are high-tension power lines. They run straight back to a patch of blue cloud along the far horizon. The path to our current state has run along a line of iterative steps. Each successive revolution has brought the next. Photographically, the book ends with “SG K #420, 2007”. This photograph is one of only a handful that includes people and is the only photograph in which people are central. A group of 9 men (I assume they are men) are in a line in the center of the frame. They are dwarfed by the night around them. Five stand while four crouch or sit huddled on the ground. A line of hills run along the horizon and are dark against a multicolored sky. The ground on which the men are set is orange and indistinct. It is unclear if this is where perhaps some original industrial beginning occurred or where and how we’ll be left at some point in the future after our industry has run us to ground.