Oksun Kim’s Happy Together has been on my mind lately. And not because my wife and I aren’t smiling lately. We’re fine, thank you. It’s been on my mind because I’ve been thinking about the state of our interconnected world at large and the way its ripples affect peoples’ daily lives.

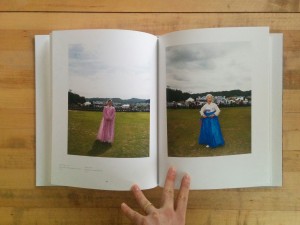

The photographs in Happy Together are portraits of mixed race couples set in domestic spaces. The Asian partner stares into the camera lens while the Western partner looks away. No one smiles. The most positive of the women betray the barest hint of satisfaction. There are male Asian partners only as part of a handful of gay couples and just one female Western partner in a lesbian couple.

Kim maintains the even keel of contemporary photography’s dispassionate, detached bathos. The subjects give little hint of what they are thinking. They seem posed, or more accurately forced. It cannot be that all intermarried couples so glum. I can’t help but wonder if a more humanistic documentary approach might not have better explored the questions and concerns Kim begins with regarding the challenges of intermarried couples in Korea.

Yael Ben-Zion’s Intermarried takes this more documentary approach and broadly explores similar ground that Kim has explored narrowly. Ben-Zion’s approach places a broader range of intermarried couples at the center of a web of interactions, artifacts and offspring. There is a wholeness to this approach and still a contemporaneous aspect in its archival research.

In Kim’s photographs, it is only the cracks in her posed facade that allow us to see who these people may be and the lives they lead: a bowl of ceramic fruit and pastries on a kitchen table; two horseshoe crabs swimming alone along a wall; the drudgery of a pile of laundry waiting to be folded; the blur of a child not frozen by the camera’s strobe; a meal waiting to be shared.

In both approaches there is a kind of underlying current of unease. Kim’s unease is evident in the question that leads to the work: “Are you happy.” And Ben-Zion’s unease is present in her tracing intermarriage through archives; she may be looking to the future but can’t help taking glimpses behind.

Ben-Zion’s subtle looks back over her shoulder don’t seem unreasonable. The world is undergoing a kind of retrenchment domestically (in many countries) and internationally. The depths and the degrees of these retrenchments are yet to be defined. For those who thought that we were on the cusp of a new tomorrow it might be time to re-examine assumptions (and redouble our efforts).

Kim’s photographs are a useful reminder that while “Are you happy?” may be a silly question to start with it is never silly to look at and to show an unvarnished (if perhaps less posed) look at what togetherness is. It is not the fairytale that wedding photographs suggest. There is inevitably complication and toil. This is true no matter who one’s partner is. And it is no less true for countries and alliances as it is for individuals and marriages. It is through partnerships that we find strength and support.

Happy Together

Kim, Oksun

2006

Support from the Arts Council Korea

Intermarriage

Yael Ben-Zion

2013

Kehrer Heidelberg Berlin

Photographs are rich in physical facts: what someone wore, where someone stood, who they stood beside, what they were doing. Snapshots serve to jog our memories of why the physical world was in this state and how we felt about the experience of being in that place at that time. Unmoor snapshots from the personal memories that give them specific meaning and they become mysteries open to interpretation and invention.

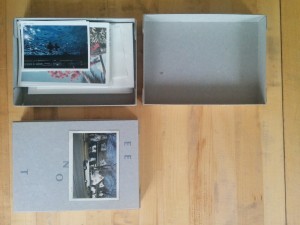

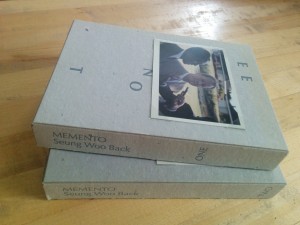

Photographs are rich in physical facts: what someone wore, where someone stood, who they stood beside, what they were doing. Snapshots serve to jog our memories of why the physical world was in this state and how we felt about the experience of being in that place at that time. Unmoor snapshots from the personal memories that give them specific meaning and they become mysteries open to interpretation and invention. This is a conceptual performance of sorts. Back poses a question and allows his chosen editors and then we, the readers, to work out the answer to it. Back collected over ten thousand vintage personal snapshots from across the US and selected 2,700 to print. These prints were then presented to eight people (one being Back himself) who were asked to select a set of eight images. These people were invited to add text to photographs if they wished. Memento One and Two are each a cardboard box containing half of the selected photographs. The “prints” are snapshot sized offset reproductions, but their varying paper base colors and surface textures mimics the feeling of flipping through a stack of old photographs. Some photographs are annotated with dates or captions in English or Korean while others are unadorned with text. Several images repeat–often with different text on them. One image of two men skeet shooting towards the ocean appears three times. As readers, we are free to rearrange and mix and match our own sets of images.

This is a conceptual performance of sorts. Back poses a question and allows his chosen editors and then we, the readers, to work out the answer to it. Back collected over ten thousand vintage personal snapshots from across the US and selected 2,700 to print. These prints were then presented to eight people (one being Back himself) who were asked to select a set of eight images. These people were invited to add text to photographs if they wished. Memento One and Two are each a cardboard box containing half of the selected photographs. The “prints” are snapshot sized offset reproductions, but their varying paper base colors and surface textures mimics the feeling of flipping through a stack of old photographs. Some photographs are annotated with dates or captions in English or Korean while others are unadorned with text. Several images repeat–often with different text on them. One image of two men skeet shooting towards the ocean appears three times. As readers, we are free to rearrange and mix and match our own sets of images.

Memento One & Two

Memento One & Two

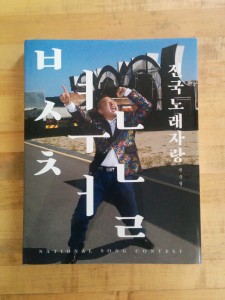

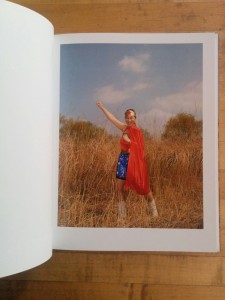

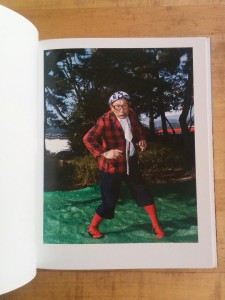

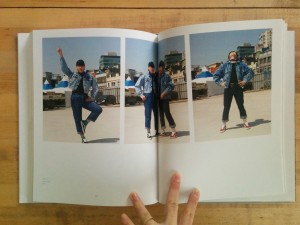

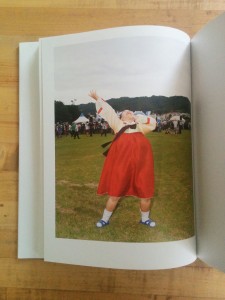

The nominal subject of National Song Contest is contestants of the television show of the same name. Running for over thirty years, the show’s premise is much like “America’s Got Talent,” if that show were combined with a comedic circus act. Choel’s subjects are full of ardor; each is a uniquely live wire. Choel does not hold them back. He seems rather to push them into hamming it up for the camera–pushing them in such a way that their acts become archetypes.

The nominal subject of National Song Contest is contestants of the television show of the same name. Running for over thirty years, the show’s premise is much like “America’s Got Talent,” if that show were combined with a comedic circus act. Choel’s subjects are full of ardor; each is a uniquely live wire. Choel does not hold them back. He seems rather to push them into hamming it up for the camera–pushing them in such a way that their acts become archetypes.

It is hard to reduce the project to a representative sample, so I’ll simply note one image that makes me smile. A

It is hard to reduce the project to a representative sample, so I’ll simply note one image that makes me smile. A  It would be naive to imagine that not one of these contestants harbors hope of fame or fortune through the contest, but it is entirely the joy of the performance that drives the photographs. If one were to shoot a similar project here in America, it would likely by tinged by an ironic sadness of the desperation for fame or the mocking overtones of the ‘loser edit.’ In contrast, Cheol’s lens affectionately finds antic joy.

It would be naive to imagine that not one of these contestants harbors hope of fame or fortune through the contest, but it is entirely the joy of the performance that drives the photographs. If one were to shoot a similar project here in America, it would likely by tinged by an ironic sadness of the desperation for fame or the mocking overtones of the ‘loser edit.’ In contrast, Cheol’s lens affectionately finds antic joy.  One might be tempted to label and dismiss Choel’s National Song Contest as camp, but this would be a mistake. The loose typographical framework, reminiscent of August Sanders’ expansive People of the 20th Century, becomes a cipher through which Choel is able to decode the breadth of “Korean-ness”. It is not only the contestants and their personas that transmit this information, but also the details of landscape and location that are the backdrop of the portraits. Likewise, it would be a mistake to forget that the photographs are a cacophony of crazy performances being conducted in enthusiastic ernest for the camera. The photographs are, quite simply, a lot of fun.

One might be tempted to label and dismiss Choel’s National Song Contest as camp, but this would be a mistake. The loose typographical framework, reminiscent of August Sanders’ expansive People of the 20th Century, becomes a cipher through which Choel is able to decode the breadth of “Korean-ness”. It is not only the contestants and their personas that transmit this information, but also the details of landscape and location that are the backdrop of the portraits. Likewise, it would be a mistake to forget that the photographs are a cacophony of crazy performances being conducted in enthusiastic ernest for the camera. The photographs are, quite simply, a lot of fun.