My last visit to Seoul came at an interesting time. My own country had just elected an orange-hued charlatan (but much loved by some, apparently) to its highest office, sparking immediate protests. Seoul was in the midst of weekly and growing protests each Saturday against an expanding presidential scandal. And multiple elections were approaching in Europe with right-wing parties gaining ground in polls. There are many people marching in the streets lately who want to see change. With all of this as a background, I came across Park Seung-hwa’s Protest published by Listen to the City in The Book Society’s stacks.

My last visit to Seoul came at an interesting time. My own country had just elected an orange-hued charlatan (but much loved by some, apparently) to its highest office, sparking immediate protests. Seoul was in the midst of weekly and growing protests each Saturday against an expanding presidential scandal. And multiple elections were approaching in Europe with right-wing parties gaining ground in polls. There are many people marching in the streets lately who want to see change. With all of this as a background, I came across Park Seung-hwa’s Protest published by Listen to the City in The Book Society’s stacks.

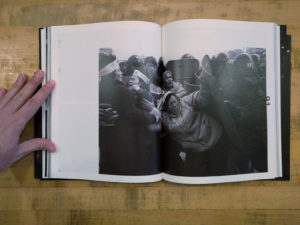

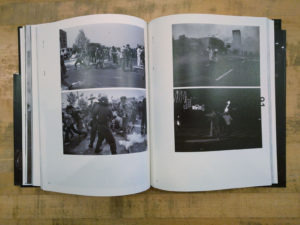

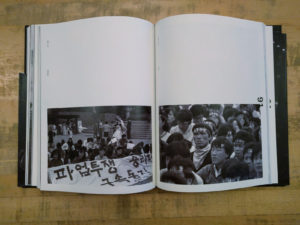

At first blush Protest appears to be straight documentary photography of the protests wracking Korea in the late 1980s and early 1990s. They have all of the gritty hallmarks of documentary and journalistic photography. However, its narrative is diffuse. It begins in the middle, goes on relentlessly for 200 pages and ends without resolution.

The photographs run the gamut from dramatic confrontation to quiet determination. There are individuals acting alone and huge crowds of people acting in concert. We are shown moments of grace and moments of violence. On one page protesters look down from a rooftop at the police below. On the next page it is the police who are on the roofs looking down on the people below. The one constant is a sense of confrontation and anger, at turns explosive and subdued. The content of the photographs is mirrored by the divided compositions in contrasty and grainy yet richly rendered black and white.

The photographs run the gamut from dramatic confrontation to quiet determination. There are individuals acting alone and huge crowds of people acting in concert. We are shown moments of grace and moments of violence. On one page protesters look down from a rooftop at the police below. On the next page it is the police who are on the roofs looking down on the people below. The one constant is a sense of confrontation and anger, at turns explosive and subdued. The content of the photographs is mirrored by the divided compositions in contrasty and grainy yet richly rendered black and white.

Park draws from his own work as well as the work of the four other photographers who formed the National Photography Research Society (민족사진연구회). These five photographers, Kwon San-Ki, Park Seung-hwa, Song Hyeok, Lee Sohye, Lim Seok Hyun, came together photographing the protests. They gathered around an older photographer, Park Yong-su. Their efforts, specifically as culminated in the publication ofProtest, are a kind of extension of Park Yong-su’s 1989 book The Road of the People (민중의 길), in which he documented the events between the 1985 sit-in demonstration at the American Cultural Center in Seoul and Chun Doo-hwan’s going to Baekdamsa in 1988. Despite this added context, a straight documentary reading remains problematic.

Park draws from his own work as well as the work of the four other photographers who formed the National Photography Research Society (민족사진연구회). These five photographers, Kwon San-Ki, Park Seung-hwa, Song Hyeok, Lee Sohye, Lim Seok Hyun, came together photographing the protests. They gathered around an older photographer, Park Yong-su. Their efforts, specifically as culminated in the publication ofProtest, are a kind of extension of Park Yong-su’s 1989 book The Road of the People (민중의 길), in which he documented the events between the 1985 sit-in demonstration at the American Cultural Center in Seoul and Chun Doo-hwan’s going to Baekdamsa in 1988. Despite this added context, a straight documentary reading remains problematic.

Park’s introduction to Protest is helpful in reframing these photographs. He reveals that the contemporary making of the book, was an effort to “uncover [his] faded passion and shell of belief” represented by photographs made over two decades earlier. These photographs are personal. They project “a kind of political intention” and come from a “‘biased’ point of view.” The photographs are at once “records, commemorations and, in a way, propaganda.”

Park’s introduction to Protest is helpful in reframing these photographs. He reveals that the contemporary making of the book, was an effort to “uncover [his] faded passion and shell of belief” represented by photographs made over two decades earlier. These photographs are personal. They project “a kind of political intention” and come from a “‘biased’ point of view.” The photographs are at once “records, commemorations and, in a way, propaganda.”

Park goes on:

Some people may not want to see them out of remorse and others may want to put the pieces of their memories put together[sic]. The fierce days of youth in the field of photography are forgotten now as they become sly oldies. Some of them have already lost their convictions. Even though they were politically pure in the beginning but now they are being misunderstood politically and contaminated non-politically. It was the time of immaturity and of glamour. It was, nevertheless, our past.

Protest then is a lament or reckoning rather than a dry documentation. It is a sober reconsideration of that time and where the flow of time has ultimately led. Despite having “walked so far away from the days of the photos…the day [Park] has dreamed of during those old days has yet to come.” He asks that the there be no mention of a “legendary saga” when reading these photos and notes that “the past [is] often glorified under the astute compromise.” We all, in order to live our lives in some measure of comfort, make compromises in our beliefs and actions; Park subtly suggests that if we are honest with ourselves, perhaps our compromises are really betrayals of our convictions.

Protest then is a lament or reckoning rather than a dry documentation. It is a sober reconsideration of that time and where the flow of time has ultimately led. Despite having “walked so far away from the days of the photos…the day [Park] has dreamed of during those old days has yet to come.” He asks that the there be no mention of a “legendary saga” when reading these photos and notes that “the past [is] often glorified under the astute compromise.” We all, in order to live our lives in some measure of comfort, make compromises in our beliefs and actions; Park subtly suggests that if we are honest with ourselves, perhaps our compromises are really betrayals of our convictions.

In a similar vein, the book presents a kind of critique of photo-journalism and documentary photography. Park defines photographs as a “record of facts.” And yet he goes on to say that a myriad of photos can be created of a single scene. “These photos are all based on facts but far away from the truth.” Park does not claim to be publishing any kind of definitive view of these events. He goes so far as to call attention to the other photographers who were photographing these same events and whose photographs, if they could have been included in the book, would have made for “a finer and richer record.”

In a similar vein, the book presents a kind of critique of photo-journalism and documentary photography. Park defines photographs as a “record of facts.” And yet he goes on to say that a myriad of photos can be created of a single scene. “These photos are all based on facts but far away from the truth.” Park does not claim to be publishing any kind of definitive view of these events. He goes so far as to call attention to the other photographers who were photographing these same events and whose photographs, if they could have been included in the book, would have made for “a finer and richer record.”

These photographs and Park’s view of their creation and value are appropriate to consider here in America in light of the protests happening in the present day. As may be self evident but certainly worth reiterating: protest in and of itself won’t bring about change. Those bodies in the streets lifting their voices may create the changes they seek or may simply gratify their desire to speak their piece. In order to effect change there must be concrete political action being taken before and after the marches, protests and demonstrations. Desiring change does not necessarily create change. It requires long years of hard work. It is equally likely that in thirty years we will look back and wonder where it all got them. Compromises for our own comfort will leave us “wandering around, or rather drifting away.”

These photographs and Park’s view of their creation and value are appropriate to consider here in America in light of the protests happening in the present day. As may be self evident but certainly worth reiterating: protest in and of itself won’t bring about change. Those bodies in the streets lifting their voices may create the changes they seek or may simply gratify their desire to speak their piece. In order to effect change there must be concrete political action being taken before and after the marches, protests and demonstrations. Desiring change does not necessarily create change. It requires long years of hard work. It is equally likely that in thirty years we will look back and wonder where it all got them. Compromises for our own comfort will leave us “wandering around, or rather drifting away.”

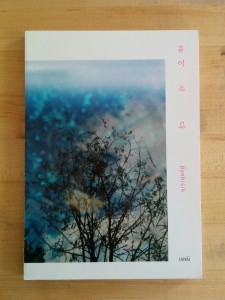

싸움 Protest

Photographers: 민사연 (Kwon San-ki, Park Seung-hwa, Song Hyeok, Lee Sohye, Lim Seok Hyun)

Photo Editor: Park Seung-hwa

Introduction: Park Seung-hwa

Essay: Han Hong-gu

Publisher: Listen to the City

2016

Design Notes:

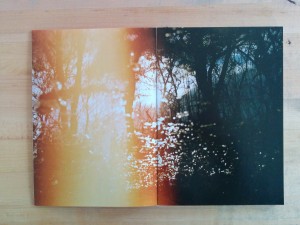

Protest is at once austere and lavish in its production. The cover is a matte black hardcover with paper wrapped boards; the title and publisher are embossed on its spine in white while the cover has only the years covered by the photographs, again embossed in white. This simple cover is wrapped in a asymmetrically folded dust jacket that folds out to a modestly sized poster with the cover imaging echoing outwards on the recto and an index of the book’s photographs on its verso. Within, the design gives structure for the images without calling undue attention to itself. The printing is richly done on a moderately heavy paper stock.

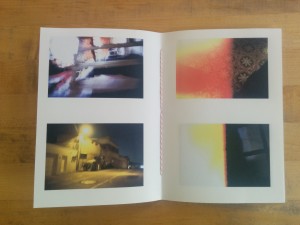

Antic-Ham’s B-Cuts has a similarly acute sensibility. It is a small book, only 14 pages, inkjet printed in a limited edition of 169 copies. It is hand sewn and features a cover cut from the book review section of a French newspaper with the title silkscreened atop the text. The photographs within and the design itself connect this book to Franticham’s oeuvre.

Antic-Ham’s B-Cuts has a similarly acute sensibility. It is a small book, only 14 pages, inkjet printed in a limited edition of 169 copies. It is hand sewn and features a cover cut from the book review section of a French newspaper with the title silkscreened atop the text. The photographs within and the design itself connect this book to Franticham’s oeuvre.  Photography is a multifaceted process, and there is opportunity for creative discovery throughout it.These photographs are primarily a product of Antic-Ham’s treating the editing with as much reverence as the shooting. As much as one creates photographs by framing the real world, it is in the editing that one makes judgements about if and how a photograph “works”. Sometimes there are diamonds to be found in the rough.

Photography is a multifaceted process, and there is opportunity for creative discovery throughout it.These photographs are primarily a product of Antic-Ham’s treating the editing with as much reverence as the shooting. As much as one creates photographs by framing the real world, it is in the editing that one makes judgements about if and how a photograph “works”. Sometimes there are diamonds to be found in the rough.

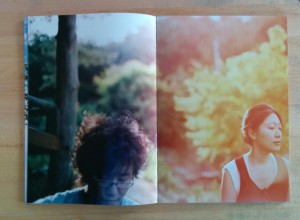

Photographs are rich in physical facts: what someone wore, where someone stood, who they stood beside, what they were doing. Snapshots serve to jog our memories of why the physical world was in this state and how we felt about the experience of being in that place at that time. Unmoor snapshots from the personal memories that give them specific meaning and they become mysteries open to interpretation and invention.

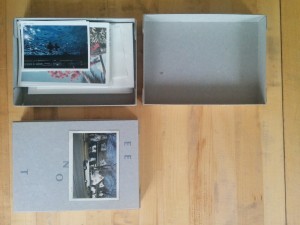

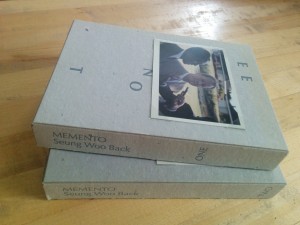

Photographs are rich in physical facts: what someone wore, where someone stood, who they stood beside, what they were doing. Snapshots serve to jog our memories of why the physical world was in this state and how we felt about the experience of being in that place at that time. Unmoor snapshots from the personal memories that give them specific meaning and they become mysteries open to interpretation and invention. This is a conceptual performance of sorts. Back poses a question and allows his chosen editors and then we, the readers, to work out the answer to it. Back collected over ten thousand vintage personal snapshots from across the US and selected 2,700 to print. These prints were then presented to eight people (one being Back himself) who were asked to select a set of eight images. These people were invited to add text to photographs if they wished. Memento One and Two are each a cardboard box containing half of the selected photographs. The “prints” are snapshot sized offset reproductions, but their varying paper base colors and surface textures mimics the feeling of flipping through a stack of old photographs. Some photographs are annotated with dates or captions in English or Korean while others are unadorned with text. Several images repeat–often with different text on them. One image of two men skeet shooting towards the ocean appears three times. As readers, we are free to rearrange and mix and match our own sets of images.

This is a conceptual performance of sorts. Back poses a question and allows his chosen editors and then we, the readers, to work out the answer to it. Back collected over ten thousand vintage personal snapshots from across the US and selected 2,700 to print. These prints were then presented to eight people (one being Back himself) who were asked to select a set of eight images. These people were invited to add text to photographs if they wished. Memento One and Two are each a cardboard box containing half of the selected photographs. The “prints” are snapshot sized offset reproductions, but their varying paper base colors and surface textures mimics the feeling of flipping through a stack of old photographs. Some photographs are annotated with dates or captions in English or Korean while others are unadorned with text. Several images repeat–often with different text on them. One image of two men skeet shooting towards the ocean appears three times. As readers, we are free to rearrange and mix and match our own sets of images.

Memento One & Two

Memento One & Two