This blog is a side project for me. First and foremost I am a working commercial photographer and a fine art photographer. Like many photographers, I am fascinated by other photographers’ work because of the ideas that it germinates in my own process. Photo-books are the primary means through which I do this.

Full Metal Jacket is not a photo book exactly; instead, it is a book of informal photographic theory seeking to tease out the cognitive and psychological elements underlying individual photographic processes. Suejin Shin brought together five photographers from different generations and different geographical locations with disparate working methods for a series of ten conversations over nine months. These conversations begin with a particular prompt and grow organically as the discussions unfold. From her introduction:

…the greatest virtue of art comes from raising questions. We began by talking shop, so to speak, about the concerns we share as artists using photography as a medium, swapping insights about our work and its limitations. We talked about what it takes to keep on producing work and why we are compelled to press on even when that spark is lacking. We asked questions to each other and found answers in ourselves.

Here then is access to the working thoughts of five of the best photographers and one of the best curators working in Korea today–or, for that matter, in photography anywhere. The photographers are Bohnchang Koo, Taewon Jang, Hein-Kuhn Oh, Oksun Kim and Sungsoo Khim. These names will be familiar to anyone who has even a passing knowledge of Korean photography. The work of most of these photographers have been discussed on this blog (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) or are in The Queue.

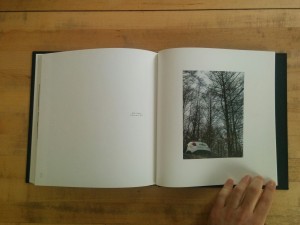

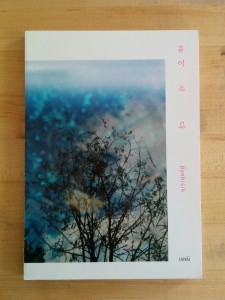

The book is broken into two volumes (supposedly sold together, though I purchased them separately from two different shops). The primary volume includes Shin’s introduction, a small portfolio of work by each photographer and three dialogs, one of which is broken into two parts. The book’s second volume is an English translation of the dialogs. The quarto sized volumes have softcover bindings with lightweight uncoated stock and very good reproduction quality. The design is simple and sparse–allowing the text and images to stand center stage.

The three topics of conversation are “Obsession: Where I Begin,” “Things That Dominate My Work 1 & 2” and “What Keeps You Working”. These three topics form a kind of operating manual for photographers. These are very much the topics that are central in books like Art & Fear, Core Curriculum or The Education of a Photographer, to name three that are on my bookshelf and ignore the dozens of others out there. What makes Full Metal Jacket unique is that it is in the form of conversations. This gives it a very accessible tone that makes engaging with the ideas under discussion easier.

This conversational form is engaging also because the reader begins formulating responses to the anecdotes being shared and questions being posed. One can feel the push and pull of personalities, too. I found myself at turns nodding and at others shaking my head. By way of example, in the first dialog abstraction and repetition are discussed. Oh says that, “Photography is an art form where where you take a very specific subject and make it an abstract theme by showing it repeatedly.” Shin disagrees with Oh’s use of the word “abstraction.” In my mind I reversed his assertion: that we take abstract themes and flesh them out by selecting, sequencing and showing very specific concrete subjects. That repetition is not making concrete subjects abstract so much as serving to make abstract ideas concrete. The discussion nudged me to consider not only how I might re-read Oh’s photographs but also how I might re-consider my own.

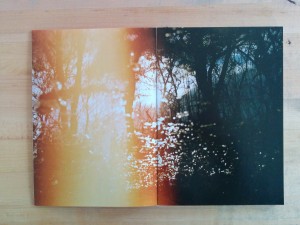

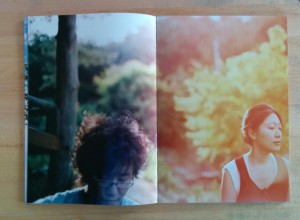

When I described the book I noted that each photographer presented a small portfolio of work or work in process. To this point, I’ve not mentioned these photographs because they are not what I feel is the driving content of the book. The photography is supplementary. It enlivens the conversation while grounding it in visual concreteness. Taewan Jang shows the work photographs that have since been published by Hatje Cantz as Stained Ground. Oksun Kim shows photographs pulled from the earlier Hamel’s Boat and some more recently published as The Shining Things. Sungsoo Khim’s portraits leave me flat while her tree studies are stark, haunting and ripe; they ought to be put into a book if they haven’t already. Oh’s “Portraying Anxiety” works are as fraught with emotional intensity as his previous portraits, though they visually blend with his Cosmetic Girls. I’d have preferred to see a larger selection of his in-process “2 Minute Portraits” that he discusses in the text. Bohnchang Koo shows a diverse range of photographs that highlights the full range of projects he’s working on and speaks about in the text. Objet 22, 2009 and Arm & Armor 03, 2010 are near polar opposites yet both wonderful and testify to Koo’s ability to assimilate anything into his personal oeuvre.

In most of the reviews that I write, I am seeking to place the work at hand into a cultural context and present a possible interpretation. This is the central functioning of criticism: to define what the work is and why it is of value (or not). In this case, Full Metal Jacket‘s dialogs do much of my work for me. I am, a bit superfluous, especially in regards to the second part of the critic’s job. I will close by simply recommending this book highly, if one can find it.

Full Metal Jacket

Suejin Shin with Bohnchang Koo, Taewon Jang, Hein-kuhn Oh, Oksun Kim & Sungsoo Khim

Assistant Curator: Youna Kim

Copy Editing: Jeongeun Kim, Kyoungeun Kim

Translation Korean to English: Yoona Cho

Design: Yeounjoo Park

Printing and Binding: Munsung, South Korea

IANNBOOKS

2013

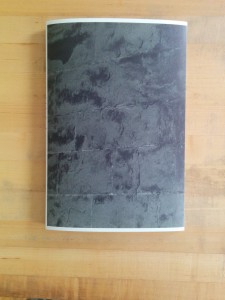

Despite the grand subject and lofty conceptual framework, Kyoungtae Kim’s Cathedral de Lausanne 1505–2022 is a rather modest affair in both its design and material construction. The brief text by Kyungyong Lim on the rear cover is short, to the point and written in language that a layperson can understand. The sum of these choices is an approachable and engaging book that encourages the reader to reconsider his or her reading of iconic landmark buildings.

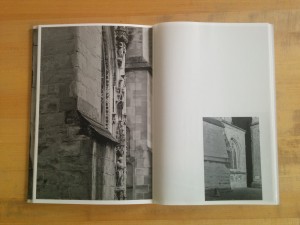

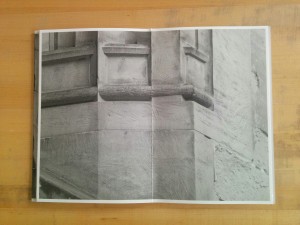

Despite the grand subject and lofty conceptual framework, Kyoungtae Kim’s Cathedral de Lausanne 1505–2022 is a rather modest affair in both its design and material construction. The brief text by Kyungyong Lim on the rear cover is short, to the point and written in language that a layperson can understand. The sum of these choices is an approachable and engaging book that encourages the reader to reconsider his or her reading of iconic landmark buildings.  The interior pages are an alternating mix of uncoated heavyweight stock and lightweight coated stock. The heavyweight pages generally contain sections of wall where either a stone is marked with the date of its replacement or sections of stone where repair work is being done. These photographs are all relatively tight close ups and printed full page. The lightweight coated pages contain longer views of either work sites or larger sections where renovations have been completed and are printed roughly quarter page. The book closes with two scenic shots of the cathedral from either end–these are printed back to back on the lightweight stock and the images ghost into one another through the paper.

The interior pages are an alternating mix of uncoated heavyweight stock and lightweight coated stock. The heavyweight pages generally contain sections of wall where either a stone is marked with the date of its replacement or sections of stone where repair work is being done. These photographs are all relatively tight close ups and printed full page. The lightweight coated pages contain longer views of either work sites or larger sections where renovations have been completed and are printed roughly quarter page. The book closes with two scenic shots of the cathedral from either end–these are printed back to back on the lightweight stock and the images ghost into one another through the paper.  As I wrote about Kim’s

As I wrote about Kim’s

Photographs are rich in physical facts: what someone wore, where someone stood, who they stood beside, what they were doing. Snapshots serve to jog our memories of why the physical world was in this state and how we felt about the experience of being in that place at that time. Unmoor snapshots from the personal memories that give them specific meaning and they become mysteries open to interpretation and invention.

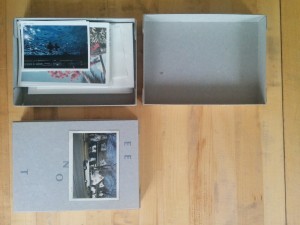

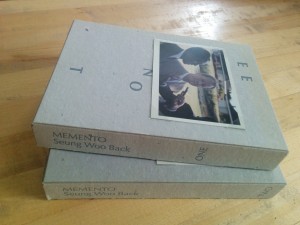

Photographs are rich in physical facts: what someone wore, where someone stood, who they stood beside, what they were doing. Snapshots serve to jog our memories of why the physical world was in this state and how we felt about the experience of being in that place at that time. Unmoor snapshots from the personal memories that give them specific meaning and they become mysteries open to interpretation and invention. This is a conceptual performance of sorts. Back poses a question and allows his chosen editors and then we, the readers, to work out the answer to it. Back collected over ten thousand vintage personal snapshots from across the US and selected 2,700 to print. These prints were then presented to eight people (one being Back himself) who were asked to select a set of eight images. These people were invited to add text to photographs if they wished. Memento One and Two are each a cardboard box containing half of the selected photographs. The “prints” are snapshot sized offset reproductions, but their varying paper base colors and surface textures mimics the feeling of flipping through a stack of old photographs. Some photographs are annotated with dates or captions in English or Korean while others are unadorned with text. Several images repeat–often with different text on them. One image of two men skeet shooting towards the ocean appears three times. As readers, we are free to rearrange and mix and match our own sets of images.

This is a conceptual performance of sorts. Back poses a question and allows his chosen editors and then we, the readers, to work out the answer to it. Back collected over ten thousand vintage personal snapshots from across the US and selected 2,700 to print. These prints were then presented to eight people (one being Back himself) who were asked to select a set of eight images. These people were invited to add text to photographs if they wished. Memento One and Two are each a cardboard box containing half of the selected photographs. The “prints” are snapshot sized offset reproductions, but their varying paper base colors and surface textures mimics the feeling of flipping through a stack of old photographs. Some photographs are annotated with dates or captions in English or Korean while others are unadorned with text. Several images repeat–often with different text on them. One image of two men skeet shooting towards the ocean appears three times. As readers, we are free to rearrange and mix and match our own sets of images.

Memento One & Two

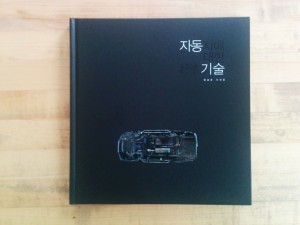

Memento One & Two Yoon Seungjun’s Automatic Description is a book of car photographs. These photographs are not your everyday glossy advertisement for this years latest iteration of automotive desire. There is no glitz, no sparkle, no sex appeal. These cars are dead.

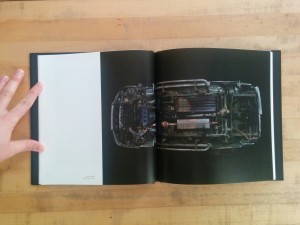

Yoon Seungjun’s Automatic Description is a book of car photographs. These photographs are not your everyday glossy advertisement for this years latest iteration of automotive desire. There is no glitz, no sparkle, no sex appeal. These cars are dead.  Automatic Description is broken into chapters that build one upon the other. The book begins with “Anatomical Chart – appropriation,” a typological series of images of individual car’s under carriages shot against a black ground. These photographs reduce the automobile to its basic structural form, minus wheels. We see the body frame with the suspension structures, transmission, driveshaft, and exhaust systems hanging from it. With their wheels removed and reoriented in space, these automobiles are no longer vehicles but rather abstract forms. Looking closely, one can find narratives in the abstraction: oil leaks, broken drive shafts, scrapes, rust and burn (?) marks. There are stories in these forms however banal they might be.

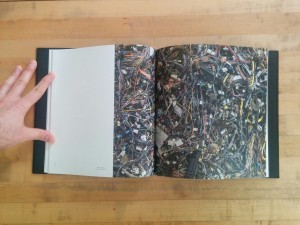

Automatic Description is broken into chapters that build one upon the other. The book begins with “Anatomical Chart – appropriation,” a typological series of images of individual car’s under carriages shot against a black ground. These photographs reduce the automobile to its basic structural form, minus wheels. We see the body frame with the suspension structures, transmission, driveshaft, and exhaust systems hanging from it. With their wheels removed and reoriented in space, these automobiles are no longer vehicles but rather abstract forms. Looking closely, one can find narratives in the abstraction: oil leaks, broken drive shafts, scrapes, rust and burn (?) marks. There are stories in these forms however banal they might be. Chapter two, “Anatomical Chart – combination,” moves from individual vehicles to the aggregation of them. Vehicles are no longer individual stories. Instead, they interlock in stacks and heaps. Crumpled cars are crumpled in a pile. Hundreds of gas tanks are mounded together. Wiring harnesses are enmeshed in a chaotic singular mess. Pipes of every description writhe together like so many snakes in a pit. The singular story has given way to a history of multitudes. Yoon brings his camera in close for these photographs. We see no ground; the subject fills the frame. We are again seeing this automotive wreckage as abstraction.

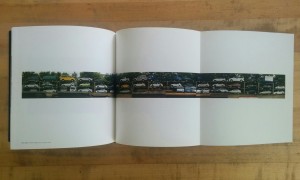

Chapter two, “Anatomical Chart – combination,” moves from individual vehicles to the aggregation of them. Vehicles are no longer individual stories. Instead, they interlock in stacks and heaps. Crumpled cars are crumpled in a pile. Hundreds of gas tanks are mounded together. Wiring harnesses are enmeshed in a chaotic singular mess. Pipes of every description writhe together like so many snakes in a pit. The singular story has given way to a history of multitudes. Yoon brings his camera in close for these photographs. We see no ground; the subject fills the frame. We are again seeing this automotive wreckage as abstraction.  “Scraped Car Chart – parade” is the third chapter and takes us off into the new territory of documentary context. Yoon has pulled back to show us the space in which these cars are resting. We see the rows of racks and risers on which the cars rest. Some of the vehicles are half dismantled; others seem as shiny as new. Sunlight glints off of chrome and polish, still. In the middle of the chapter a gatefold presents a long panoramic image of column after column of junked cars. There are obvious joints in the image; it is not a singular panorama. Yoon has constructed this image–no different than we have constructed this entire infrastructure of disposal (such as it is). Just as the infrastructure of roads, highways and city streets has been built to accommodate the relentless drive of automobile culture so has an infrastructure been built to support the end stage inherent in consumerism. When millions are buying cars, millions are inevitable discarding them as well.

“Scraped Car Chart – parade” is the third chapter and takes us off into the new territory of documentary context. Yoon has pulled back to show us the space in which these cars are resting. We see the rows of racks and risers on which the cars rest. Some of the vehicles are half dismantled; others seem as shiny as new. Sunlight glints off of chrome and polish, still. In the middle of the chapter a gatefold presents a long panoramic image of column after column of junked cars. There are obvious joints in the image; it is not a singular panorama. Yoon has constructed this image–no different than we have constructed this entire infrastructure of disposal (such as it is). Just as the infrastructure of roads, highways and city streets has been built to accommodate the relentless drive of automobile culture so has an infrastructure been built to support the end stage inherent in consumerism. When millions are buying cars, millions are inevitable discarding them as well.